Yearly roundup lists highlight the best films to come out that year, they can be a tool to lift smaller films out of obscurity, or a sort of hegemonic force, in those years when a large swathe of popular critics declare the same three films the best of the year. Something that might be forgotten though, is that we all tend to watch a lot more than just new releases each year, and some of our favourite watches aren’t new at all, but personal discoveries of filmic gems from years or decades ago. With that in mind, some members of the film society committee decided to highlight some of our favourite watches of the year, with a mind on choosing films that were new to us, but not necessarily new releases. We hope you enjoy reading, that you find something for your watchlist you might not have previously considered, and that you have a very happy new year.

Diego Collado — President — Nashville (1975)

Robert Altman’s Nashville was a great discovery for me this year, screened at the BFI as part of their Altman season in June. Although an incredibly popular filmmaker, I had never come across one of his films before.

Fellini’s Amarcord being one of my favourite films of all time, I find stories with such an impressive number of characters quite captivating. Somehow, these talented writers manage to distil a person, with their past, future, and present, into a glance, a sigh, or a specific gesture, which is all that these smaller yet still complex characters need to do to express themselves among such a large ensemble cast. Take, for example, Pfc. Glenn Kelly in Nashville. Altman and Tewkesbury’s characters quickly materialise, with only a few lines, right before the camera moves to a completely different part of Nashville, leaving the audience with blanks to fill while the camera chases someone else down the streets of the city. The film was a thrilling experience and a great introduction to Altman’s world.

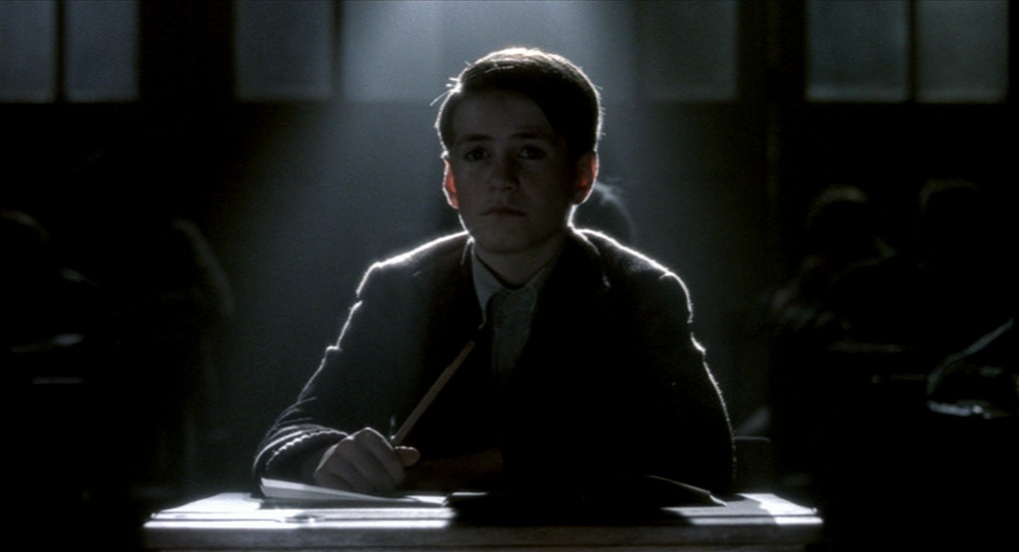

Lydia de Matos — Blog & Podcast Editor-in-Chief — The Long Day Closes (1992)

I’m unsure of the last time I was hypnotised quite like this. Watching The Long Day Closes feels like watching what cinema could be, if the art form were distilled into its purest purpose and practice. A collection of remembered moments, observed and (re)constructed with infinite care, the film takes on the qualities of memory itself, existing not simply as a product of memory, but an almost frighteningly accurate evocation of it. I write this aware of just how acutely pretentious it sounds, and yet The Long Day Closes is, for lack of a better phrase, immensely approachable. It is richly textured, almost endlessly so, constructing an atmosphere which envelops, until the spectator can’t help but feel themselves a part of the very fabric of the film. Not having been aware of Terence Davies until a friend recommended this film, his filmography has now been catapulted to the top of my to-watch. It may simply be that The Long Day Closes concerns itself with precisely the subjects which I find most interesting, but regardless of that it feels like essential filmmaking; the best film I’ve seen all year, if not the best film I’ve ever seen.

Saul Lotzof — Treasurer — Incendies (2011)

As a big Radiohead fan, hearing You and Whose Army? playing over the opening shot Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies gave me the feeling that I was in for a real treat. Whilst the film employed possibly the worst usage I’ve ever witnessed of some irrefutable ‘bangers’, I think my initial instincts were mostly right; it came off very well on the whole. The film is about a daughter and son who, following their mother’s death, are prompted by her will to track down their unknown father and unheard-of brother. It flashes between this current-day quest and the war-torn past depicting the mother’s often convoluted ties to their estranged family members. A categorisation of genre seems difficult without spoiling some important details — on a very primitive level, it’s a drama-mystery-thriller-sort-of-thing.

It wasn’t my favorite watch of 2021 (that accolade goes to a film that I feel like I couldn’t gloss as briefly or lightheartedly), but it made a greater impression than most others this year. I loved how it was cut and how it looked; the muted palette, understated camera movement, and gentle pace made much of the appalling action in several scenes even more disturbing. The commitment to a certain ‘realism’ puts us right up against the horrors of the modern world without the buffer of the fantastical ‘Hollywood’ rudiments endemic to much contemporary commercial Western cinema. At least, that’s what I thought until the twist, which in my mind did not match the grounded ‘vibe’ of much of the film that came before it — for me, it was too theatrical and artificial. On balance, however, it was an excellent film, and one that is well worth a watch.

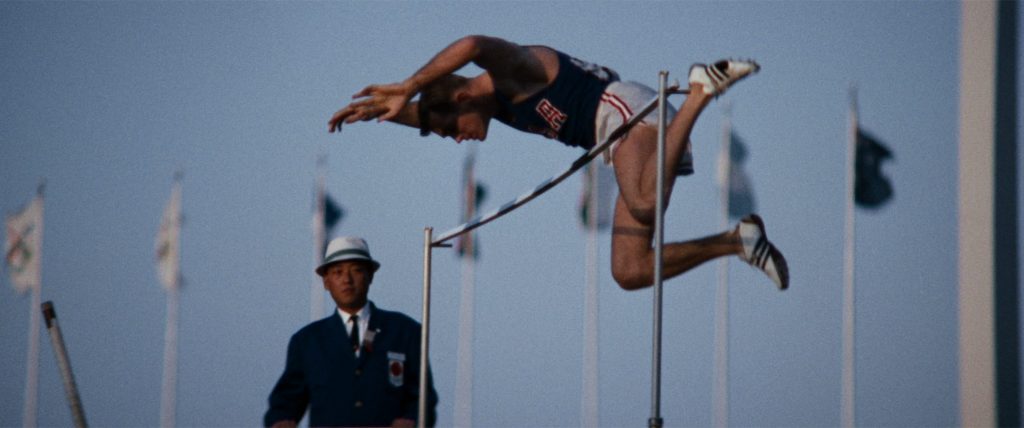

Tomi Haffety — Documentary Officer — Tokyo Olympiad (1965)

Never before have I been so transfixed by a marathon, a long jump, or a spectator’s reaction to a failed somersault. Kon Ichikawa takes archival footage from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and by miracle makes it into an arcane tableau that not only follows athletes, but humans at the pinnacle of their ability. Every four years the Olympics rolls around and we experience a two week stretch of gawking at how much determination, discipline and ambition the athletes put themselves through in order to reach superhuman levels of strength. It always becomes an emotional affair, I think, to marvel at how hard these people have worked, only to often walk away empty-handed. Tokyo Olympiad celebrates every success and failure with the respect they deserve, capturing the moment a pole-vaulter realises he’s never going to make it, or the relief on a marathon runner’s face as they finally cross the finish line. As a documentary, it is both insightful and amusing in a way that captured me for its full three hour stretch, because as well as capturing the sport, it captured the lives of the athletes outside of the arena, and thus documented the external context of the sport. The 1964 Olympics was a demonstration of geopolitical calm, solidarity, and prosperity, and this is laid bare in Ichikawa’s presentation of the event. The shots of Tokyo across the November fortnight show the reality of life outside of the glamour often ascribed to global events like this one. This is not my only great watch of 2021, but it is certainly the one that, through its humour and playful editing, resonated with me the most, even if I felt deservedly unfit and inferior after watching it.

Pedro Tafur — Workshops Producer — Love in the Afternoon (1957)

Billy Wilder’s films are always funny and always sad. In the endless squabblings between Joe and Jerry in Some Like it Hot, in Norma Desmond’s delusional monologues in Sunset Boulevard, and in the deceitful love triangle formed by a thin twenty-year old virgin, her widowed father, and a rich casanova in this brilliant romantic comedy. Trying to protect her from the hurtful reality of love, private inspector Claude Chavasse has kept his daughter Ariane confined to a tiny Parisian flat where she spends her days practising the cello and secretly reading her father’s reports on unfaithful wives. After saving a Mr. Flannagan’s life from a revengeful husband who had hired Chavasse’s services, innocent Arianne begins visiting the international playboy in his suite at the Ritz. While romance flourishes between them, we fall in love with the images of Paris in the 50s, with the waltz music performed by Flannagan’s private quartet of travellers, and with Audrey’s face which goes from laughter to tears as Wilder puts words in her mouth. If you can find an afternoon during these holidays, watch this masterpiece, I promise, you will fall in love.

Alexia Mihaila — Blog & Podcast Editor-in-Chief — Last Night in Soho (2021)

Last Night in Soho feeds off nostalgia and like most films that do so, I adore plunging right into it. The story follows a first-year UAL fashion student, Eloise, who communicates with a sixties aspiring singer, Sandie, through her dreams. Whilst the plot is somewhat predictable and tries to push a moral message which falls a little short, the magnetism of the leads, the aesthetically pleasing cinematography carry the film through.

Named after the 1968 hit by Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich (yes, that’s a real band name), the film certainly continues Wright’s tradition of jam-packed soundtracks, and I’d add this to that last list of elements which truly made the film, this being, for me, one of the best soundtracks of the year.

One of the most charming parts is being able to spot the film’s locations whenever I’m out in London, the setting being so close to UCL. I still listen to the soundtrack on repeat, something which keeps me longing to rewatch, but I must admit if it weren’t for Anya Taylor Joy’s deep soulful eyes prolonging the mystique and keeping the audience intrigued, the soundtrack wouldn’t have been enough to sustain the neon-classy upbeat culture of the film’s sixties London. Ultimately though, Last Night in Soho is the perfect balance between commercial clichés and artistic vision, and I recommend it for a good time!

Elinor Sharples — Videography Officer — The Power of the Dog (2021)

I admittedly pressed play with some reservations, since I’ve never been particularly thrilled by Westerns. And, at first, I wasn’t particularly convinced by Cumberbatch’s character, Phil — whose primary occupation seemed to be appearing at odd moments simply to stand there while whistling an ominous tune at his new sister in law, Rose. But, as The Power of The Dog began to unfold, I found myself becoming slowly more and more intrigued by the characters, and by the subtlety underpinning their merging storylines, especially towards the ending.

That said, as compelling as the story and the performances from Benedict Cumberbatch, Kirsten Dunst, and Kodi Smit-McPhee were, what rooted this film in my mind as the standout of 2021 was its cinematography. The characters are framed in both the great outdoor planes and the indoors in such a way (especially with the use of windows, I might add) that the quiet tension that persists and grows throughout the film becomes even more palpable. The name Ari Wegner is on a lot of people’s tongues at the moment, and I can’t help but wonder if we will soon hear it uttered by whoever announces the Oscar for Best Cinematography this year. It’d be a spectacular first that’s been a long time coming – astoundingly, only one woman has ever been nominated for the category, and no woman has as yet won.

It’s difficult to tell yet whether or not this movie will cement itself in filmic history and popular culture in the same way as The Piano (or as The Power of the Dog’s character Phil would call it, ‘the Pinano’) has, but I can say this much: Jane Campion has returned to the feature film game at her very best.