Aadesh Gupta reviews the final season of the crime and legal drama television series Better Call Saul and its bond to its predecessor Breaking Bad.

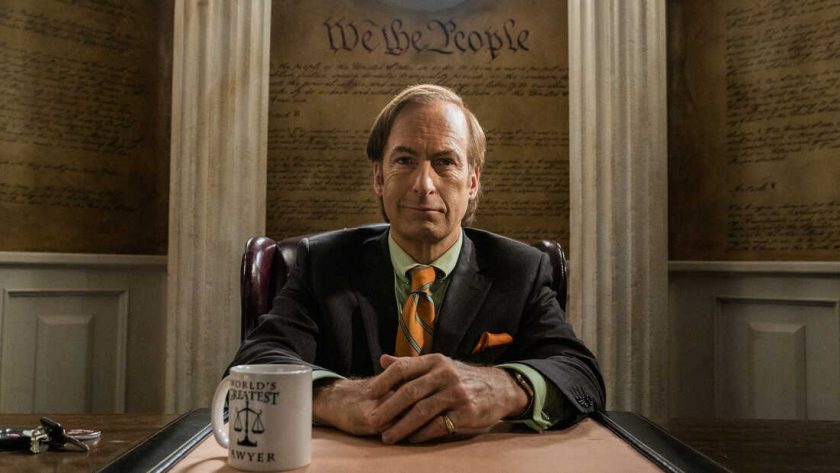

Witnessing a man change. A deceptively simple idea with an undeniable potency. It’s what captivates me the most about Breaking Bad. Character arcs have been employed countless times in films and TV, but rarely do they ever reach the visceral sentiments of Walter White’s moral decay. A journey of sheer emotion, overflowing with blood, meth, and tears. Its prequel series, Better Call Saul, presents us with the tale of another corrupted soul, James McGill, who we formerly knew as Saul Goodman. The new downfall story is not as concerned with the change our titular protagonist experiences as it is with his inability to change: one of the many powerful moments of the series that reflects this theme is the conversation between Walter and Saul: ” So you were always like this ? “.

This is Walter’s condescending response to one of Saul’s clumsy mistakes and it’s not an entirely fair comment on his behalf. Walter’s transformation from an ostensibly innocuous chemistry teacher into the drug kingpin Heisenberg is not the process of some anonymous evil permeating a pure soul. An ego existed in him from the very start, and his story involves him succumbing to it over time. Comparably, Saul Goodman also existed from the very start, as the steady dwindling of Jimmy’s innocence. Despite Chuck being easily antagonizable, his perception of his brother wasn’t unfounded.

I know you. I know what you were, what you are. People don’t change.

Whether it’s Jimmy, Saul, or Gene, he couldn’t resist the schemer in him all along. Where Walter changes by giving in to his evil, Jimmy fails to change by constantly reverting to it. In episode nine of the final season, the moment we’ve been anticipating from the very beginning of the show finally arrives. The camera gradually dollies into Jimmy’s back, as his last ounces of humanity and compassion vanish, leaving behind a façade of shadiness. After eagerly waiting six seasons for Saul Goodman, we’re left longing for James McGill, as the man we initially saw as a cardboard cut-out of comic relief, is revealed to be an empty vessel of tragedy.

In a world of courtrooms, cartels, and dented trash cans, we’re given an unforgettable array of intricately written characters, whose lives finally collide in this final season. Nacho’s bottled-up agony and him transcending the criminal archetype, Lalo’s psychopathic tendencies and hubris akin to Gus, Jimmy and Kim’s tender romance alongside their inherent incompatibility of morals, Howard’s affirmed professionalism against cheap obstinacy, and Mike’s hardened exterior concealing his damaged core.

It all meshes in a wildly shocking yet miraculously orchestrated manner. The reverse engineered plot points allow for elegiac arc completions, immensely rewarding systems of setup and payoff, and add meaningful subtext to Breaking Bad’s narrative. Furthermore, every single member of the cast delivers unbelievably sophisticated and personal performances, elegantly complementing the incomparable writing in carefully deconstructing the psychological dispositions of their characters. While noticeably slower in its pace and smaller in its scale, when compared to the predecessor, its meticulousness, is second to none.

Scrupulous details bring to life the complex logistics of the characters’ criminal procedures and the familiar spaces they operate in. On top of the effective escalation of suspense, the showcase of individual characterisations and aesthetic satisfaction, displaying these elaborate mechanics firmly aligns our experiences with those of the people we are observing. It’s all grunt work that unites with all the other skillful technical aspects to create a sense of tangibility for the world.

Masterful visual storytelling is another area where perfectionism is evident. DP Marshall Adams collaborates with Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould to realise a truly remarkable, at times hypnotic vision. Extensive usage of wide shots, practical lighting with palpable shadows, and playful imagery are some of the cinematographic choices that form a seamless amalgamation of western, noir and comedy. It’s a combination of genres that works surprisingly well, but predominantly as a result of the cautious craft, especially the balance between the drama and the quirks. Inspiration has been drawn from many artworks including classic cinema, namely The Godfather, and even paintings such as Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, but the end result is still tremendously unique. Narrative elements are also conveyed through symbolism, which utilises a variety of props and colours, or lack thereof in the suitably lifeless Gene storyline. From Nacho’s integrity embodied by a lone blue flower in the harsh desert to Lalo’s ghastly return depicted by the ominous flickering of a candle, many purposeful examples of this are scattered throughout the final season.

In the end, Jimmy/Saul/Gene finds himself in a predicament that even his slick showmanship will have trouble getting out of, so the only place left to look is the past. It’s fitting then, to end on a series of reflections and regrets, followed by confessions and acceptance. Melancholic cigarettes and gunslinger gestures: one last sign of redemption, revitalising the love that was once lost. A gentle, poetic ending that’s just enough to fill you with an inexplicable poignancy and catharsis. I would have never thought that a spin-off based on the one-dimensional comedic lawyer from Breaking Bad would, in my eyes, ultimately outshine its hugely acclaimed predecessor and become the best show I’ve seen. As the final moments of the show unravel, and the camera pans to the right onto the wall, cutting to black, I know I’ve watched one of my favourite pieces of storytelling.

Stream Better Call Saul now on Netflix: