The FilmSoc Journal is back for the 30th edition of the Raindance Film Festival, the largest independent film festival in the UK.

Aadesh Gupta reviews Park Chan Wook’s cult classic Oldboy, a neo-noir action thriller following a man’s life of vengeance after 15 years of imprisonment.

“Laugh and the world laughs with you. Weep and you weep alone.”

This is one of the many poetic conceptions echoing throughout Park Chan-wook’s 2003 masterwork and Raindance Maverick, Oldboy. It’s a cynical thought but also a fitting one for a film that dives right down to depths of human depravity. Protagonist Oh Dae-Su (Choi Min- sik), having been released after 15 years of seemingly baseless imprisonment, learns to abide by this principle, shielding his torment with an unshakable urge for revenge. Eventually he discovers that his vengeful pursuit is enshrouded by that of his captor, whose schemes reach an unthinkable degree of sadism.

For those who have not seen the film, it may seem like a straightforward ultraviolent revenge thriller, but it comes with unforeseen twists that shock you to your core. However, it should be noted that these twists are far from shallow and instead function more like a psychological thrust of a knife, jolting the audience out of ease. The premise alone is enough for this – Lee Woo-Jin (Yoo Ji-tae) detains Oh Dae-Su with a television as his only window into the outside world, giving him a slightest hope for life and thus exacerbating his hunger for it.

As a result, a harmless man like Oh Dae-Su is transformed into a brutish spectre of wrath. Behind his noirish cloaks, there’s nothing left of him except a thirst for vengeance. This is a man reduced down to an animal. His innocence is stripped away, and his behaviour is turned rugged. He is no better than a beast, but does he still not have the right to live? His lover, Mi-do (Kang Hye-jung), may give his life a semblance of virtue, but this is subdued by the all- encompassing cruelty. Nevertheless, the rhetorical question continues to persist as Oh Dae- Su’s hope for some rectification in an otherwise hopeless journey.

In the process of adapting the original manga, Park envisions his subjects and scenes as if they were pulled right out of a Japanese comic. This becomes clear from the opening, where hasty electronic music permeates the soundscape and a low angle shot against the sun reveals Oh Dae-Su with his mane-like hair. However, this tone is dropped almost instantly when we’re pulled back into the present. A jaggedly edited scene exhibits an alcoholic Oh Dae-Su in a police station before his imprisonment. He clumsily tumbles around the room and plays with the angel wings that he bought as a birthday gift for his daughter. Such a striking polarity in characterisation could have been easily mishandled under a lesser director, but Park keeps each moment wholly compelling. This feeds into the overarching tone of the film too which is at one moment utterly gut-wrenching, and at the next, darkly humorous. Through this sophisticated tonal chaos, the film gives purpose to its shock value and becomes a distortion of emotion.

Feelings are warped temporally as Oh Dae-Su contemplates: “If they had told me it was going to be 15 years, would it have been easier to endure?” His initial emotions may deform as his experiences change, but that doesn’t invalidate them. This is accentuated in certain moments where a brutal event ends on a delirious laugh; a supposedly absurd response to violence but also one that avoids the veneer of social constructs. Other works tend to make such eccentricities seem superficial, but here they unfold truths about our elusive nature.

In fact, the realisation of truth also shows the extent to which we are trapped within our nature. Oh Dae-Su steps out of his small prison and into a “bigger prison” which is his exigency to find the truth, but this confines him in another agonising dilemma. Lee Woo-Jin is also constrained by his desire for revenge, and so Park paints a portrait of two men, both troubled by their pasts and eternally trapped by their nature. The layered voyeurism complements this idea as we join Lee Woo-Jin in thoroughly studying Oh Dae-Su, thereby taking an exacting look at his human condition and therefore our own.

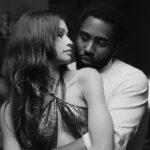

![Oldboy – [FILMGRAB]](https://film-grab.com/wp-content/uploads/photo-gallery/07%20(768).jpg?bwg=1547240710)

All in all, Oldboy is an incomparable Jacobean tragedy rendered at an Oedipal level. Its inventive imagery is absurd, sickening and yet always transfixing. Classical music imbues it with a sense of majesty and idiosyncrasies, ranging from a weaponised tooth brush to the consumption of a live octopus, giving it a strange charisma. It’s fascinating as a formal object and haunting as a character study. Throw in two extraordinary lead performances, one of the greatest fights put to screen and a serving of sadomasochism, and then you get a tour de force of cinema.

Watch the trailer for Oldboy here: