Sungleen Moon explores the cultural impact of recent smash-hit Netflix show, Squid Game.

By now, you either have the strongest self-discipline for not succumbing to the internet’s social pressures, or you have binged-watched the entirety of Netflix’s new show Squid Game (2021). Squid Game has wrapped its tentacles all around and placed the world in a chokehold. Everyone is talking about it, and everyone wants to keep talking about it. But why?

“How about you use your body to pay?”

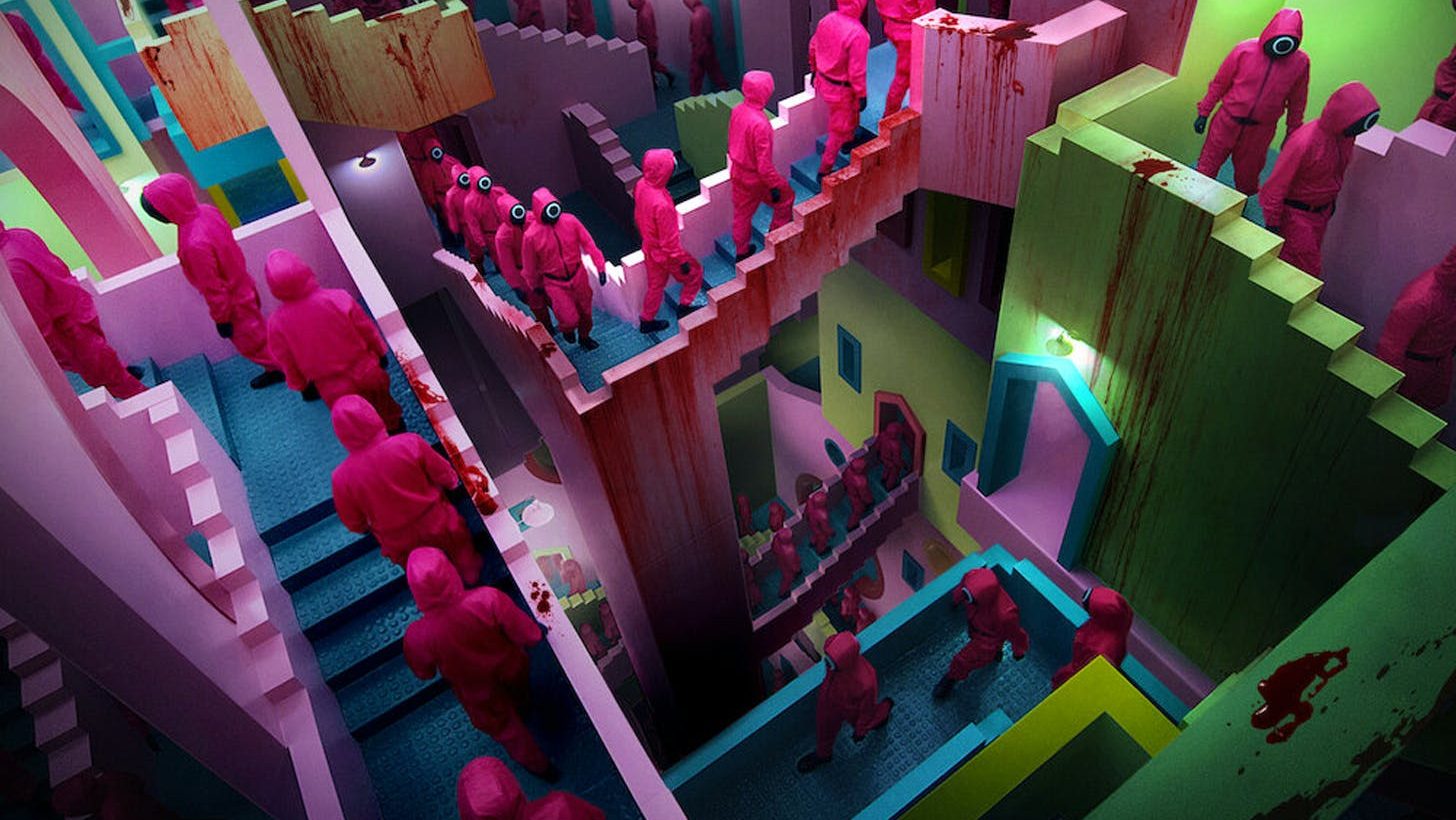

Under the flirtation of bountiful cash sitting inside a piggy bank chandelier, 456 debtors take a trip down memory lane and play childhood games in order to meet eyes with the prize. The sole winner is rewarded generously with the sum of 45.6 billion Won (£28.2 million). The losers are paid with death.

As we follow the 456th player, Seong Gi-hun (a struggling father with a gambling addiction whose dire circumstances have restricted him from being able to provide for his family) into the game, we find the players stripped of their humanity, dignity, and morality. They eat, sleep, and kill for a sliver of a chance to win. Squid Game’s unique concept is that the players have all signed a contract. They have all “chosen” to participate because the gamble for an economically secure life is better than the daily struggle of a working-class debtor.

There are also multiple subplots that focus on a detective and one of the guards of the game. These can be narratively perplexing at times and can disrupt the pacing of the main story, however, they add further depth to the thematic discussions of class commentary, and the corruptness and incompetence of authority. Squid Game is rife with emotional backstories, tense sequences, disturbing plot twists, and the plotline is sure to keep audiences engrossed throughout the nine episodes — a key factor in why the show has been such a success.

Bandits, Butchery, and Betrayals

As the game progresses it is the characters and their developed relationships that carry the tension and action, and our connection to the sympathetically rendered individuals that forces us to press “continue watching”.

Like many Netflix shows, Squid Game has reignited discussions on representation in media. Oddly, even Forbes has added their own expertise into the discussion of representation, writing that the comical and stereotypical characterisation of the rich white Americans was “so annoying” …okay, Forbes.

Despite Squid Game being produced in a mainly homogenous country, one major character that resonated with many viewers and a fan-favourite was Anupam Tripathi’s Ali. It was surprising for many K-Drama fans to see a little bit of diversity in the main cast, as past K-Dramas have excluded or made caricatures of non-Korean people of colour. It can be argued that Ali’s character in Squid Game is to be sympathised with rather than dehumanised. We see Ali, a Pakistani migrant, face abuse that intersects both race and class. We cry with him when his desperate efforts to provide for his family becomes defeated, when he is mistreated at work, and eventually when he is traitourously used for another one’s gain.

Including Ali, we follow an ensemble of outcasts, consisting of various individuals that have been traditionally neglected or oppressed by society: a gambling addict, a migrant, a North Korean defector, a murderer, a financial fraudster and an elderly man with a chronic illness. We put aside our prejudice, and root for the disenfranchised antiheroes: cheering their success and crying at their inevitable, butchered demise.

An Ode to the Past

Not only does Squid Game owe its success to the Korean Drama Renaissance, but the show also reminds audiences of its cultural predecessors, which feature a similar survival concept that we all know and love. As the Gods Will (2014) and Alice in Borderland (2020) are comparisons that come to mind, with the writer admitting that he took direct inspiration from the mangas Battle Royale and Liar Game.

Squid Game offers us the best elements of what we crave to see in the survival genre. We are hungry for moral evil, fascinated by human gore and horror, and are intrigued by the extreme absurdity of the games.

“Dropping all my money”

As a Korean myself, it was astonishing to see the rising popularity of the show. As I mindlessly scrolled through the endless TikTok videos on my ForYou page, more and more videos of Squid Game took over. The algorithm swiftly transformed into viral videos and challenges featuring my favourite childhood Korean candy, dalgona. Not just dalgona, but many more nostalgic trinkets of my Korean childhood started to dominate mainstream media (yes, even the beloved actor Gong Yoo).

Squid Game has provided an outlet for current media crazes, from people attempting the various TikTok challenges inspired by Squid Game, to people obsessing over the stars of the show.

Capitalism sucks

It has been nearly two years since Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite (2019), cinema’s biggest “screw capitalism” movie, has graciously blessed our screens and demanded all film watchers around the world to venture over the “one-inch tall barrier of subtitles.” Two years later, another form of Korean media critiquing the vicious qualities of capitalism has captured worldwide attention, terrorising Netflix subscribers to click on the unusual television series that has somehow managed to surpass its fellow Western shows and sneak into the No.1 spot on Netflix.

As much as the story and game’s structure is outlandish and absurd, it is strikingly reflective of the world we live in. I mean, who would willingly participate in a game just for a chance of making it… am I right?

Squid Game is all fun and games until we realise it’s undoubtedly based on reality. Do the players really have any choice in participating in the game? Do the disenfranchised really get to choose whether to compete or not? Even the mastermind behind the hit series, Hwang Dong-hyuk, revealed his own struggles in the workforce. Hwang, who completed the script by 2009, was continually rejected from studios and was left financially struggling, resulting in him having to sell his laptop for money. Hwang’s story shouldn’t be an admirable, work-hard-until-you-succeed story. Rather, it should be a reminder of the gruelling conditions faced by many in poverty.

Not only are we fascinated by Squid Game’s concept and characters, but also as viewers, we are deeply engrossed in how our world works on a micro-scale. The show should not make us question: what would you do if you were a player? But rather, what are you doing now in our own world of Squid Game?

It’s an Asian thing

From Bong Joon-Ho to Park Chan-Wook, South Korea’s media quality is not an issue in the country’s soft power production. However, with the success of both Parasite and Squid Game, it must bring into question why Western audiences are so specifically engrossed with non-Western media that violently portrays capitalism, and why it has the capability to rise in the Western charts. Parasite took home the major Western awards, including the Palm d’Or, and secured notable titles at the Oscars. Likewise, Squid Game is an international hit and has become Netflix’s most-watched series as of September 17, 2021, reaching the number one spot in ninety countries around the world.

So, why is the West obsessed with Eastern critiques of capitalism?

The sensationalisation of Eastern media spotlighting the vices of capitalism has almost made us distance ourselves from the problem of wealth inequality onto international waters. By watching the disturbing dynamics unfold in both Squid Game’s battlefield and Parasite’s modern mansion, we remove ourselves from the gory narrative. By consuming East Asian media through a Western lens, it is easy to become accustomed to the idea that dysfunctional capitalism is an Asian, Eastern, even Oriental obstacle, rather than a global one.

The corruptness of the VIPs and the guards, the brutality of the killings, and the players’ desperation for security and safety becomes associated with Eastern faces and landscapes, rather than our own doorsteps.

Oftentimes, Western media that claims to be critical of capitalism, ends up attracting fans who aspire for that lifestyle (I’m looking at you Wolf of Wall Street (2013)). Or, Western films that comment on the exploitation of the vulnerable are never too explicit of their real presence in our daily lives, distorting reality from fiction. Popular 2010s dystopian adaptations (e.g. The Hunger Games (2012)) feature social revolutions that are aimed to disrupt positions of power. However, the dystopian settings are clearly set in a world that is much different and alien from our current society. Oh, The Hunger Games? That’s something that will happen in the future. Even the thoughtful anti-capitalist movie, Sorry To Bother You (2018), includes a psychedelic and fantastical twist that removes the viewer from contemporary America.

Parasite and Squid Game are explicitly set in the present, capitalist, gruelling South Korean society. Therefore, as Western audiences, we are compelled to think that we have it better in the West whilst watching the on-screen horror. It creates an illusion that we are the VIPs, watching Netflix from the comfort of our homes when, in reality, we are also players of the same game. This is why we are so fixated on this new show, another addition to the catalogue of “dystopian” or “science-fiction” media that Western audiences consume already.

Let’s talk about the red hair (spoliers)

Our hair is not just a fashion accessory, but also an external manifestation of our inner identity. It reflects our lifestyle, our status, and our emotions. Therefore, it is not surprising that viewers were caught off guard when the lead protagonist suddenly changed his hairstyle from the common-man black to scarlet red.

Throughout the series, Seong Gi-Hun had been an empathetic, kind, and inconspicuous individual. He blended into the background as he chose to associate with people who were at a disadvantage, always caring and warm-hearted. This changes in the last few moments of the first series. His hair, indicating his inner self, now alludes to boldness, anger, passion, and possible bloody revenge. The sudden change in hair colour is not only a topic of comedic discussion but an indicator of his newfound character development. We wonder with our imagination who this reinvented Gi-Hun is and what his aims are. What is he planning to do? The show creators ultimately tease for a possible second season as we are left with an open ending.

The ending’s ambiguity left audiences disappointed, with Netflix to blame for once again trying to squeeze another season out of a complete story. Initially, Hwang Dong-Hyuk mentioned that he did not want a second season, with a possible suggestion that the show creator would hire multiple experienced writers instead if there were to be one. Although not officially renewed yet, there has been much talk for a possible continuation of the story due to its sudden triumph.

The ending is a catalyst for frustrating thoughts or a trigger for exciting anticipation and another contribution to why Squid Game has become such a talking point.

Squid Game is currently streaming globally on Netflix: