As deodorant becomes ever more crucial, parks become more picnic blanket than grass, and grass becomes watered with chicken wine, it is clear that summer …

Riding the French New Wave: A Summer Series

The home of film at UCL.

As deodorant becomes ever more crucial, parks become more picnic blanket than grass, and grass becomes watered with chicken wine, it is clear that summer …

Sothysen Tuyor reconsiders Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) fifty years after its release and three years after being voted …

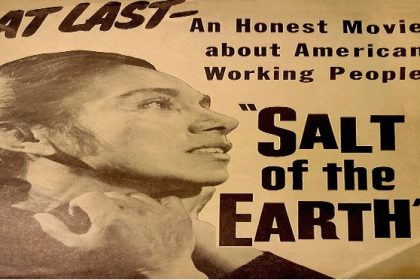

Edward Lahner looks back on Herbert J Biberman’s Salt of the Earth, telling the remarkable tale of its production and reception history from the McCarthy …

Carys Manjdadria-Jenkins returns to the end of the twentieth century (and possibly the world) the final instalment of Gregg Araki’s sci-fi Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy. At …

Carys Manjdadria-Jenkins looks back on Powell’s controversial horror with its unflinching 4K restoration. The 4K restoration of Michael Powell’s 1960 psychological horror Peeping Tom indulgesthe …

Anya Somwaiya reviews Korine’s debut feature, Gummo, a mood board for the decades that followed. Scotch taped wall bacon. Albinos and drunkards. Girls with noeyebrows …

Sub-Editor Mayra Nassef takes a look at the cultural impact of genre-bending The X-Files following its 30th anniversary screening at the Prince Charles Cinema, asking …

At the end of a fantastic year for cinema, these are the films that defined ours. While most of the films listed had their UK …

FOMI director, Alex Dewing, takes us through some of the filming locations of British Drama AdULTHOOD. This article was written as part of the celebration …

Dan Jacobson looks at what Danny Boyle’s vision of the apocalypse has us believe about London and lockdown. This article was written as part of …