These are the movies that made our year. Whether you want to compare your list of favourites to ours, or read about some of the gems you missed or our guilty pleasures from throughout the year, here’s a comprehensive list dedicated to another outstanding year of cinema. Happy new year!

Aftersun, dir. Charlotte Wells — Madeline Choi (Co-Editor in Chief)

Charlotte Wells’ directorial debut is a heartbreaking family story about the bond between a father and his daughter. Told through the eyes of Sophie (Frankie Corio) and her childhood camcorder, the film approaches topics of memory, loneliness, and nostalgia in the most gut-punching way possible. Wells subtly asks us to read between the lines, created by a young Sophie, as we see her father (Normal People’s Paul Mescal) struggle with his mental health and addiction problems. Wells’ weaving of camcorder footage with the film’s simplistic landscape reinvents the film format from a story of memory to one of haunting meditation. The film’s contrapuntal tones of childhood innocence and melancholy is done so smoothly; it piles up these little moments until it topples over. I, for one, could not leave the cinema with dry eyes.

The nostalgic set of a holiday resort paired with the chemistry between Frankie Corio and Paul Mescal allow for one of the most vulnerable father-daughter portrayals I’ve ever seen. The film really encapsulates it all: the fun times, the frustration Sophie holds against her father as she’s coming of age, the aching love and struggle of a parent…Despite its serious themes and slow-burn pacing, Gregory Oke’s beautiful cinematography and top-notch soundtrack (there’s something so poetic about my favourite sequence of the year playing to Bowie and Queen’s “Under Pressure”) bring perfect balance to the melancholy tone of the film; somehow that makes it even more devastating.

You can read Madeline’s review of Aftersun for the Journal here

Crush, dir. Sammi Cohen — Alexia Mihaila (Journal Co-Editor in Chief)

Despite its numerous underdeveloped plots, corny jokes and jajune-written script, Crush is a step forward into enlarging the queer cinema catalogue. As a lighthearted, coming of age rom-com, its importance engenders in the context of this genre flatlining in the women-loving-women community after the early 2000s.

The film fosters a millennial yet forward-thinking approach to portraying sexuality as showcased by the talent of the latest gen-z Disney alumni such as Girl Meets World’s Rowan Blanchard and Moana’s Auli’i Cravalho. It follows the story of Paige, a CalArts high school applicant (played by Blanchard), and the love triangle between her lifelong crush and track star darling Gabriela (played by Isabella Ferreira) and her twin sister AJ (played by Cravalho). The film feels like a safe space, with no coming out story, and it doesn’t play on toxic past sub-genre tropes such as failed relationships, and even cheating to show how the ‘grass is greener on the other side’ as in Imagine Me & You (2004). What Sami Cohen brings to the table, in her directorial debut, are just heartwarming rom-com tropes in their pure form, making it your average coming of age cutesy superficial mainstream portrayal of two people falling for each other and who also happen to be queer women.

Granted, it’s far from being the best film I’ve seen come out this year, but it’s surely been my guilty pleasure. It’s sweet, it’s short and whilst the humour might seem on-the-nose, it manages to give life to the easy-watch rom-com subgenre in the queer film space.

Top Gun: Maverick, dir. Joseph Kosinski — Jenny Windbrake (Studio, Equipment & IT Manager)

Top Gun: Maverick as my favourite 2022 release was an easy choice. This film had me in its grip throughout its entirety! After going to the premiere, talking to Tom Cruise (yes, I’ll tell the story to anyone who will listen), and actually getting to watch the film at the premiere as well. I was, as some would put it, obsessed. As this is a sequel to a film that was made over thirty years ago, the writers had successfully managed to overcome the challenge of coming up with a story that relates to the first film while still engaging the new generation. The storyline is simple, yet engaging, nostalgia-provoking, and attracts devoted viewers who’ve loved the fast jets and witty Maverick over the past decades. But, of course, the actual highlight of the film, besides the legendary beach scene, is the making of the flight sequences. Not only did they film real jets for the flight shots, but all the cockpit scenes were also actually filmed in real-life jets, up in the air. For that, the actors had to direct and film themselves and undergo intense pilot training even to be allowed to fly in one of the F18s; definitely worth checking out the making-of clips on YouTube. Overall, it’s a highly entertaining film and despite not being an indie-vibe film, I’d still recommend it to anyone interested in film-making.

The Good Nurse, dir. Tobias Lindholm — Barbara Kononova (Drama Producer)

An un-romanticised portrayal of a prolific serial killer that pulls focus on system issues, Lindholm’s film is a salient directorial work of contemporary true-crime cinema. Unlike his feel-good Oscar winner Another Round (Danish: Druk, 2020) The Good Nurse (2022) is by no means a joy ride. Based on Charles Graeber’s 2014 biography, the film opens with the novel’s preceding events in Pennsylvania’s St Aloysius hospital, where Charles Cullen (Eddie Redmayne) is suspected of murder by insulin administration to the ICU patients. Cullen, currently serving multiple life-sentences at New Jersey State Prison, has yet to confess his motives, and Lindholm intentionally shifts the audience’s focus from the “why” to the more fundamental question of “how”.

The portrayal of Cullen as a serial killer avoids conventional tropes. Redmayne’s character does not appear mentally compromised, but rather asserts himself as a reliable and dependable figure. He offers solace in sharing the workload of, a single mother and coworker, Amy Loughren (played by Jessica Chastainburden). Despite being diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, Loughren remains private about her condition to the hospital board due to her demanding schedule and lack of health insurance; meanwhile, Cullen’s affectations blindside her into disregarding his criminal involvement. However, the film holds more in its story than mere homicidal manipulation.

The Good Nurse foregrounds this reality of corruption by almost making the healthcare system an agent in the crimes as much as Cullen was. Nearly every scene is an indignity: corpses left neglected in beds and loved ones grieving next to the sickly glow of a vending machine. Redmayne’s on-screen performance poses a potent dilemma – whether a good person corresponds to their representation, or whether there resides a contrary to their behaviour.

P.S. I had to give an obvious shoutout to my Scandinavian filmmakers.

Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu — Saul Lotzof (President)

I’m not sure how much I can be trusted to write a faithful review of Bardo three months after watching it, so this will be more of a tongue-in-cheek recommendation rather than anything critical. I saw Bardo during the BFI London Film Festival and loved it, though perhaps Iñárritu’s onstage introduction emotionally affected me before it even started. As an ardent fan of films like Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) and Sorrentino’s La Grande Bellezza (2013), Bardo fulfilled my obscure desire for overly meditative, indulgent and melancholic ageing male protagonists, trying to make sense of the kaleidoscope of memories that seem to comprise their identities. I think that where 8 ½ and La Grande Bellezza are quite distinctly positive in their conclusions, there is a certain wistfulness to the end of Bardo that sets it apart from the other two. Go see it!

Pearl , dir. Ti West — Laura Martin (Workshop Producer)

Pearl is a beautiful example of an intriguing character study film of an inherently flawed and malevolent character. The film presents the dichotomy of nature versus nurture, showing Pearl (Mia Goth) as both a girl that has been raised in a loveless home, but also as someone with malicious, sadistic urges from birth. Despite being the main villain of the X franchise, we are made to sympathise with Pearl through the powerful, emotive monologues along with Mia Goth’s incredible acting. Pearl is presented as an outcast who never gets what she wants, tugging on the heartstrings of the audience in a way that makes you forget everything she’s done throughout the film. The mise-en-scene of the film along with the gorgeous cinematography also makes Pearl for a great watch.

The dynamic between Pearl and her mother depicted in this film also presents an interesting facet of mother-daughter relationships. The mother was forced to sacrifice her individuality to survive in the world, causing a resentment to form between her imprisoned state, and her daughter’s youthful freedom. Mother-daughter relationships are supposed to be comforting ones however, the mistreatment of women in our society has led to many girls having to fend for themselves and even compete with their fellow women, meaning that often mother and daughter are pitted against each other. Despite Pearl’s difficult relationship with her mother, we can see at various points how she still craves her mother’s approval and affection, but these needs are never met. (Perhaps if they were this film would have a very different ending but who knows)

Ambulance, dir. Michael Bay— Çağrı Ustaoglu (Studio, Equipment & IT Manager)

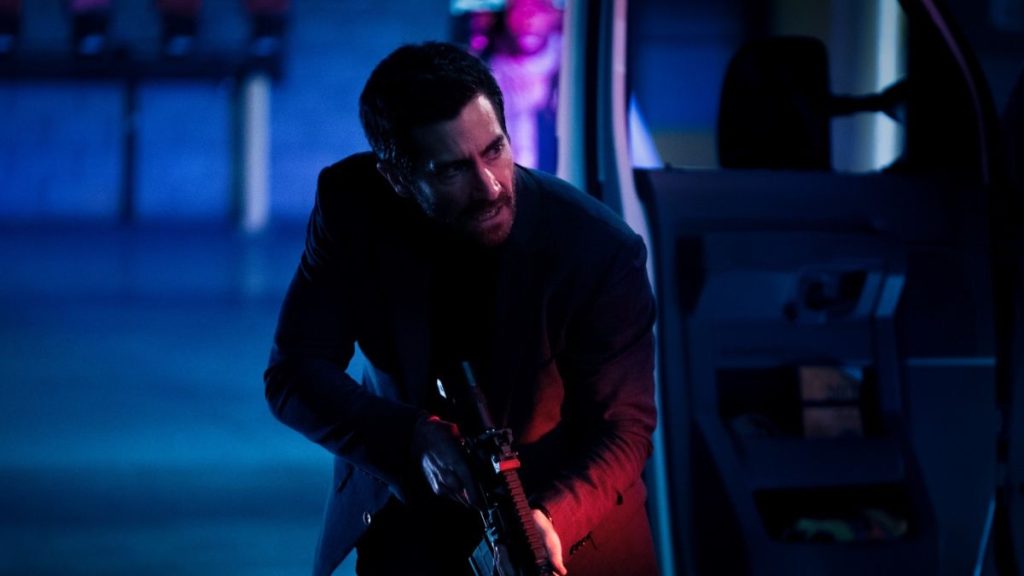

Despite being just another Hollywood action film that is fast-paced, filled with wacky drone shots, slow-mo’s, explosions, terrible police drivers, and scenes forged through conventional character backstories that try to rip some emotion out of you, I can confirm now that Ambulance is the most Michael Bay film of all of them. Essentially, it’s just one long car-chase, but it has become an instant classic to me. I must admit, I did watch the film at 1 a.m. after a drive home from a beach day in Bournemouth and it was the perfect, switch-your-brain-off type of popcorn entertaiment. it also featured some fun performances from Jake Gyllenhaal and Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, and a notable performance from Eiza Gonzalez. Highly recommend it for an instat rush of blood to the head!

Glass Onion, dir. Rian Johnson — Tony Yang (Screenings and Socials Producer)

As someone thoroughly entertained by the playful riff on classic whodunnit tales that was 2019’s Knives Out, I walked into the screening of Glass Onion with bated breath. Considering this was the first sequel in director Rian Johnson’s filmography (The Last Jedi notwithstanding), I wanted to see how his trademark subversion of expectations would be deployed against preconceived notions of both a beloved genre, and the groundwork established in his previous film. The result? A 139-minute thrill ride that swings at the fences with style.

Set during the summer of 2020—a time that feels distant yet all too familiar—Glass Onion feels like a contemporary period piece. Much as Agatha Christie’s novels explored societal developments and issues of her day, this film’s kaleidoscopic host of characters embodies various archetypes of our social media age: fabled and inscrutable tech billionaires, opportunistic political streamers, disastrously insensitive celebrities. They serve as a lens through which Johnson examines the underlying ecosystem, the unstated assumptions and firmly entrenched beliefs that propel such figures to success. If Knives Out was a more constrained take down of the wealthy and privileged, Glass Onion positions it front and centre, in a twisty murder mystery that closely incorporates these themes in both form and structure.

All this to say, Glass Onion is a crowd-pleaser in every sense of the word. An excellent ensemble cast carries the humour and momentum of the story, while gorgeous cinematography and an evocative score lend the film an identity distinct from its predecessor. Not to mention the various celebrity references and cameos, which manage to delight and not distract. Regardless of if you were a fan of the original, or simply looking for a slice of thought-provoking holiday entertainment, I’d recommend this film!

Fire of Love, dir. Sara Dosa — Nat Ng (Documentary Producer)

Katia and Maurice Krafft’s story sounds like something out of Wes Anderson’s imagination: two quirky French volcanologists meet, fall in love, spend their lives documenting volcanic activity around the world, and ultimately perish together in the 1991 Mount Unzen volcanic eruption. But to distill their relationship and their lives’ work to that one sentence doesn’t do them, or the documentary, any justice. Pieced together from the vast amount of archival footage that the Katia and Maurice accrued over their time together, the film contains some of the most awe-inspiring shots of nature I have seen, with one of the most breathtaking shots being Katia, in her surreal-looking silver suit, walking calmly in front of a gigantic red blaze of oozing lava. Each shot is a feast for the eyes, which is surprising considering this footage was mostly used for research/documentation purposes. At once explosive and tender, I think this a beautiful example of what documentary filmmaking can achieve.

Noche de fuego / Prayers for the stolen, dir. Tatiana Huezo — Pedro Tafur (Workshop Producer)

Four years ago, Alfonso Cuarón won the Best Director category at the Academy Awards with a Spanish-speaking film about the life of an indigenous housekeeper in Ciudad de México. Following the success of Roma, producer Nicolás Celis decided to go to work on a new Mexican project set in a rural village in the state of Jalisco, the far removed home of Ana, Paula and María.

Noche de fuego tells the story of these three girls, of their school lessons, their magical games and their mother’s struggle to hide them from the men of the pick up trucks. Ever since Mexico replaced Colombia as the main distribution hub of Cocaine, the cartels have become the masters of the country’s rural lands. But in Jalisco they do not grow coca, they grow opium poppies. So as the camera gazes through the fields where Ana and her mother work, it seems as if we are looking over a limbo of red poppies where silence has ruled for thousands of years. Then Ana hears the sound of guns and all the girls run back to their homes.

After Hollywood surrendered to the charm of their Southern neighbours cinema, Mexican directors were able to write their country’s stories. Unlike Roma, Tatiana Huezo’s film is not an autobiography and the three girl’s stories are not her own, but after watching Noche de fuego it is clear that only she could have directed this film. In the same way as nobody else could have played Anna’s character other than a Mexican teenager whose acting career began when Huezo asked her if she wanted to play the role. Only this film could tell the stories which are now taking place in the valleys of Jalisco. These stories needed to be told, and they need to be watched.

Holy Spider, dir. Ali Abbasi — Artemis Gitiforoz (Archive Officer)

You should never buy those prepackaged tubs of pomegranate. They’ll always be mushy and quite frankly tasteless. If you want that deep blood colour of the pulps and its rich acidity, cut it open yourself, spend your evening peeling it out, and have it stain your skin and clothes.

I saw ‘Holy Spider’ (Dir. Ali Abbasi) at this year’s BFI festival during what were the early days of protest in Iran’s current revolution. I had got my ticket pretty last minute and as a film dilettante I knew practically nothing about the director. But lucky as the fool usually is, I got the perfect introduction. There he was, with the lead actress and the producers to give a short talk before the screening. By the way, that’s also when the pomegranate began to peel. Whether Iranian, in solidarity with the movement or just a film buff, there was a common understanding that the regime is vile and oppressive, apathetic and inhumane. Yet as we approached the pulps, our clothes were splashed with red. Abbasi told us that when we see the horrors in his film, to not point fingers at the villains and treat them as totally abstracted forces. He asked us to look at ourselves, at the undercurrents of our culture that may have given rise to the obscenities portrayed in his film. An approach that has universal worth.

Just like his words, ‘Holy Spider’ doesn’t take the prepackaged mushy attitude. The film is brutal in all tenets of its art: acting that won first place at Cannes, cinematography that at times shows what you think is too much but is really an exact balance of reality and poeticism and a story that unveils the hard-heartedness of fanaticism. We all left that theatre stained red from the peeling back the perspective Abbasi had given us. Nevertheless, his film provides a rich and alternative viewpoint, one of introspection and one that is vital for us all to taste, especially during a revolution.

Crimes of the Future, dir. David Cronenberg— Aryan Tauqeer (Journal Sub-editor)

“It has meaning, very potent meaning, and many, many people respond to it” mutters Timlin (Kristen Stewart), a squirrelly bureaucrat defending the artistic integrity of the live surgeries that performance artists Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen) and Caprice (Lea Seydoux) orchestrate throughout Crimes of the Future. Much the same could be said of Cronenberg’s film, which resurrects his career-long obsession with the ontological transformation of flesh through humanity’s subsuming of technology in a late-period work that is at once eerily contemporary in its exploration of state’s infringement upon bodily autonomy, and yet markedly classical in the structural clarity of its almost Costa-esque compositions- the looming caverns that humanity has retreated into as new Pantheons of performance.

The director’s Ballardian fixation on techno-eroticism and violence as catharsis is transposed here in the form of the almost symbiotic relationship between Saul and Caprice- the former’s body is practically a walking mutation, generating organs whose induced discomfort Mortensen conveys with admirable vigour, shuffling around abandoned shipyards in a black cloak as a sickly, suffocating spectre of a future yet to come.

Existing within the same continuum as the rhythmic rending of flesh set to the droning synths of a career-best Howard Shore score, however, is a deeply tragic tenderness between Saul and Caprice, artists and lovers desperately attempting to derive some semblance of passion from a world absent of all sensation-even pain. As cuttingly amusing as its metatextual commentary on Cronenberg’s career (not to mention the fervent divisiveness his art typically inculcates) may be, it is doubly affecting as an artist’s reckoning with not just his legacy in the face of mortality but with the nigh-certainty of ecological decay. Echoing with the eternal tragedy of the war to control the body, the film remains the most transcendent work of the year, in all its beauty and its horror.

You can read Aryan’s essay on Cronenberg’s filmography for the Journal here

Good Luck to You, Leo Grande, dir. Sophie Hyde— Farida Ezzat

This film hums with honesty and heartbreak. I absolutely loved the quiet intimate moments where desire spoke tenderly but louder than words. I know the film soars with sex positive messages yet it’s its unique sensual energy that I admire the most; it left me simmering and sighing as the credits rolled. The overall flow of the film across days felt seamless and genuinely engaging especially for a dialogue-heavy two-hander. Emma Thompson and Daryl McCormack both deliver delightful performances and their effortless chemistry is a spectacle to enjoy and envy.

Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers, dir. Akiva Schaffer — Euan Toh

I admittedly have not watched many films in 2022. I looked through my Letterboxd and there’s only one film that makes sense to nominate as my favourite of 2022…Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers! At no point would I say this is a great movie. It’s good, not great, but way more entertaining than some excellent movies. Seriously, the only movie I’ve seen this year that I might want to watch again is this one, just because it’s so ridiculous. The film is a reboot of the 1989 cartoon of the same name, and that’s about all that you need to know before going into this one. If you haven’t watched the original cartoon, just go in blind. If you have seen it, one thing to note is that the playfulness comes out through an incredible blend of animation styles, a meta narrative and solid voice acting. It’s the most fun film of the year for me. Embrace the absurdity.

The Banshees of Inisherin, dir. Martin McDonagh — Aadesh Gupta

Martin McDonagh’s latest feature exhibits the most deceptively simple premise of his oeuvre: an abrupt end to a lasting friendship. A sudden severing of an unbreakable bond, which forms the bedrock for an exploration of humanity. At first, the clash of various masculinities seems to dictate the social dynamics, but a core existential pain is soon revealed. Pride and despair intertwine as characters contend with loneliness and mortality, hurting those that care for them in the process. As a result, a melancholic undertone is established, and the work is infused with poignancy. The artistic dexterity on display here is of no shortage either. Taking us on a journey of humour, sorrow, and severed fingers, McDonagh steers effortlessly through tonal disparities without losing his balance – something we’ve come to expect from him. Stylistically, he forgoes the purgatorial grittiness of his debut feature, In Bruges, for something more majestic. Further complemented by cinematographer Ben Davis’ stunning (at times Malickian) frames and composer Carter Burwell’s eccentric score, the film allows McDonagh to make an urban-to-rural transition in a seamless manner. Out of everything I’ve seen this year, The Banshees of Inisherin is the film that moved me the most, and for that reason it stands as my favourite of 2022.

The Fabelmans, dir. Steven Spielberg — Aziz Almashari

Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical film is a metatextual visual meditation on the filmmaker’s bittersweet upbringing, displaying the tremendous potential of the medium to re-record and reinterpret memory. Proclaiming that The Fabelmans is simply yet another entry to the ‘love letter to cinema’ canon is an achingly surface level account – Spielberg’s piece asserts that leading a creative existence is as harrowing and sorrowful as it is illuminating. Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle), is a direct manifestation of Spielberg’s adolescence; he searches for a modicum of control over his environment behind the supernatural force of the lens of his camera. Encircled by the sphere of familial strife, characterised by the duality of his father Burt (Paul Dano) and mother Mitzi’s (Michelle Williams) union, along with his jocular uncle Benny (Seth Rogen). An isolating epiphany dawns upon Sammy, leading him to believe that his emotions are only ever processed through 8mm film, a vessel which translates what he feels, leaving him an empty shell when deprived of its functions. The Fabelmans thus presents a simulacrum of a life rehabilitated and lived, through and in tandem with cinema.

The film dances with the form, interrogating the sacrificial essence beyond the moving image, while critically investigating the traditional Spielbergian pathos. Even in the comforting flashes of melodrama, naturally woven into its narrative framework is the surreal, where Spielberg uses the film as a confessional – he admits that the filmmaking process is intrinsically exploitative and cruel. Moulding personal, shared trauma into an artistic work may achieve catharsis, yet it is still a hauntingly unethical operation. The film momentarily breaks the fourth-wall following John Ford’s (David Lynch) advice to Sammy on artistic perspective, where a self-reflective Spielberg manages to communicate the truth that despite being a veteran filmmaker, he will always attempt to be perceptive, both as an artist and human being. The Fabelmans is a portrayal of the collective false image – those hopeful, romanticised, yet neglected aspects of our lives that may or may not have existed.