LEAFF 2021 celebrates its sixth year with a programme of thirty films from celebrated and debut filmmakers. Championing East Asian cinema, LEAFF aims to bring a wide range of cinema to London and offer the opportunity to experience a new culture of cinema.

Tomi Haffety reviews a multi-director anthology piece about the secrecy and loneliness of the everyday.

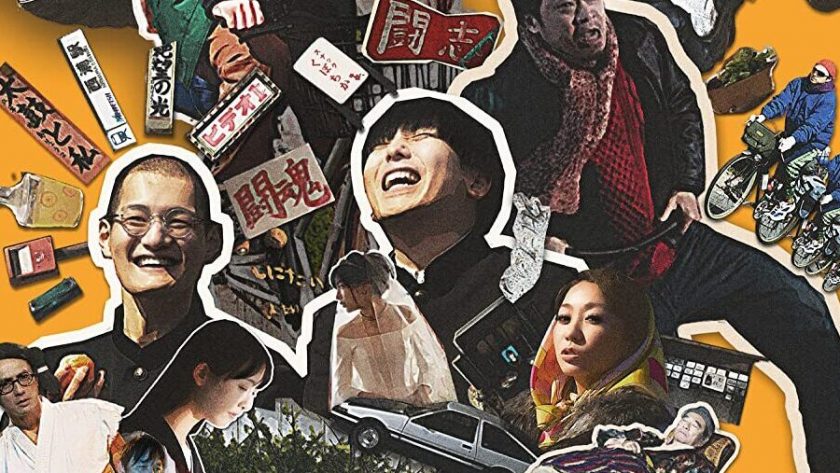

Zokki is, in a word, goofy. While watching, I couldn’t help but be struck by the absurd quirkiness of the five interlaced stories that carry the film through different lives, timelines, and locations. Co-directed by three of Japan’s leading creatives, Takenaka Naoto, Yamada Takayuki, and Saitō Takumi, this anthology brings together questions of coincidence, luck, and secrecy.

A sleepy port town in western Japan wakes up on a summer’s day and prepares to go about its daily routines. A grandfather makes his granddaughter breakfast, before telling her in a casually profound manner that he has over 200 secrets. A man wakes up his neighbour with an earthquake-sized door slam before cycling off to try and find himself. Three other idiosyncratic tales start just like this; the sheer normality of the everyday suppressing the unconventional stories that unfold. The kaleidoscope of detail found in each becomes heightened by the mundanity which surrounds it, and the film’s first quarter is so slow-moving that it feels like a long climb to the top of a style-over-substance shaped hill. Throughout, there are often scenes that feel oddly placed, as if they have no relevance to the plot but are simply there to add unexpected oddity to a film about suburbanites telling their stories of secrecy. There are lifeless middle-aged men getting drunk by the loading docks, haunting mannequins that talk, a sterile video store, a distant grandfather-granddaughter dynamic, and fictional siblings, all of which make for an animated, fast-paced quintet of stories, but which often feels too much, as though the stories are getting lost inside each other. Overall though, that is the point of the film. Each story is happening within another, and the timeline of events is completely skewed until the final ten minutes when it all comes together and everything that you’ve worked so hard to understand becomes clear.

Undoubtedly, my favourite, albeit the most unorthodox tale was the friendship between two high school misfits. Ban (Joe Kujo) is weirdly obsessed with Makita’s (Yūsaku Mori) older sister, as well as constantly drawing ‘I want to die’ over every blank space around school, and goes to great lengths to get anything of hers in his possession. As this story unfolds, the boys’ nerdy, antithetic relationship becomes more intense and culminates in an emotional argument steered by misunderstandings and secrets. Significant locations in this story appear repeatedly throughout, linking each segment of the film in a cunning journey through saturated hues and magical music, and particularly ingenious and unexpected camera angles. Ban is an extremely unlikeable character who, much like his male counterparts in the other stories, is fixated on having sex with an older woman to such an extent that he infiltrates their real and imagined lives. It becomes obvious here that the three directors are men, and the peculiar framing of women is disrespectful and objectifying. Because of the dissonance between stories until each’s very final scene, I became bothered by the use of female characters as satirical plot points which only facilitated the male protagonist’s story. I put this down to the sustained gender inequalities that are rife throughout the Japanese art industry and came to see the film as situated in the context of modern-day Japanese storytelling.

Similarly, I couldn’t help drawing similarities to the magical realism of modern Japanese literature. The work of Haruki Murakami and subsequent authors like Toshikazu Kawaguchi has shaped a genre of Japanese creativity that feeds well into this film, which is based on a collection of Manga stories by Hiroyuki Ohashi. This also explains why, beneath the fast-paced comedy, there lies an exposure of human fragility. Interwoven into each story is first and foremost the theme of secrecy, but also of rejection of the outsider. Each character is alike in the way that they are all in some way, cast aside, and left alone in society, and this ultimately creates a rapport between the viewer and the character, because with every story you become more invested in the overarching omnibus that ties the segments together. The fractured storytelling is often confusing, but the sweet cyclical ending ties up any loose ends, purposely reminding you that the directors were always in control, that there was method in the madness.

Zokki is out right now: