Shayeza Walid reviews a pandemic project from the creator of Euphoria about a couple whose relationship unravels over the course of an evening.

The word ‘eccentric’ is defined as “unconventional and slightly strange”. And although Malcolm and Marie stretches beyond the boundaries of this word many times – entering the realms of grotesque and even absurdist theatre in its 106 minute runtime – simply put, it is an eccentric film about an eccentric couple, who say some poignant, frustrating and, well, eccentric things.

It is hard to describe Malcolm and Marie in just a few words, because, in all honesty, the film is saturated with so many of them. With long speeches about art, politics, cinema, life, and the couple’s complex relationship; the dialogue driven by anger, jealousy, insecurity, love, the need to explain the self, but also win every argument – words, not action, are the film’s flesh and blood. The premise is simple to begin with, but the more we are made aware of the characters’ pasts, the more complicated and confusing the film becomes.

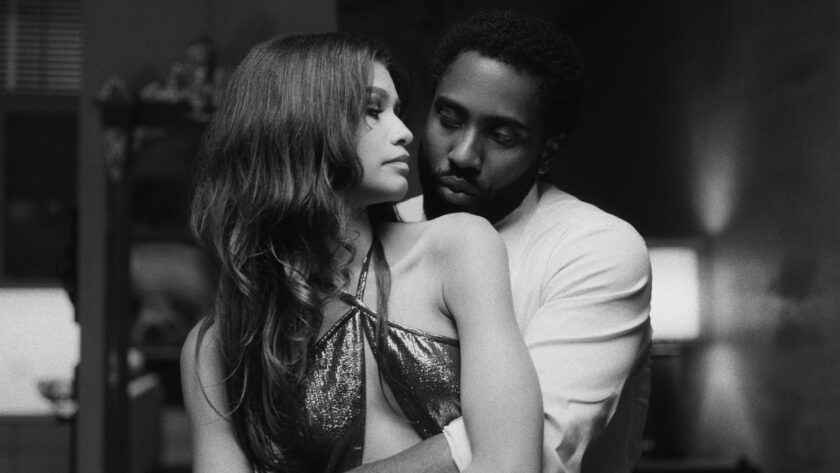

In Malcolm and Marie, written and directed by Sam Levinson (Euphoria), an immaculately dressed couple (John David Washington and Zendaya) return to their savvy Los Angeles home from Malcolm’s latest film premiere. Malcolm is in particularly good spirits, since the audience seemed to enjoy his work, drawing comparisons to auteurs such as Spike Lee and Barry Jenkins. However, despite his elation, Marie doesn’t share the celebratory mood. An argument ensues, and we find out that Malcolm forgot to thank Marie in his opening speech at the premiere, resulting in her becoming enraged. This argument, although being partially put to rest, does not end, and spans the rest of the night, as the two lovers peel back the many layers of their relationship.

From the moment the movie begins, Levinson’s screenplay hits audiences with reveals that re-contextualise Malcolm and Marie’s relationship in real time. Through the series of arguments we find out that Marie is a recovered addict with a dark past, who gave up dreams of becoming an actor. Meanwhile, Malcolm is a struggling artist who has finally received praise for making a film largely based on Marie’s struggles. Between the moments of quarrelling, when the couple displays passionate sexual tension or takes a break from arguing, a glimpse of their connection can be seen. This connection is not one of love however, rather one of codependency. Resultantly, instead of feeling empathetic we find ourselves rather exhausted by the couple’s toxic bickering – their highs purely physical, their lows emotionally rupturing. While the arguments start relatively small, they snowball as the film goes on. Malcolm and Marie falls into the trap of telling rather than showing, and becomes dissatisfying at times.

In addition to its general wordiness, sometimes we are also made to feel flustered, because the characters’ anger seems not to be derived from each other or their personal insecurities, but from external thoughts about other topics. In these moments it feels as though the characters are trying to justify and explain the film that they are in. From Malcolm’s rant about all ‘black films’ being considered political, to one about the true meaning of art, followed by Marie’s claims about the life of people in Hollywood – there are stretches of the film where it seems as though Levinson is voicing his frustrations with the state of the film industry. These monologues, while offering some serious food for thought to the audience and bringing to light both actors’ concrete acting abilities, do feel out of place. The scenes do not add to the general trajectory of the plot, nor do they justify the characters’ generally erratic behaviour.

Putting aside the draining aspects of the film, Malcolm and Marie does have redeeming qualities. It is beautiful to watch, providing respite from its exhausting plot. Shot in 35mm black-and-white, each frame seems to be packed with meaning and an artistic purpose, bringing a sense of methodic theatricality to the film. This brings me to say, that what is truly great about Levinson’s film (although it is a view I am aware many may not share) is that it is bold art that does not shy away from being overtly pretentious. From the fact that everything takes place in the early hours of the morning, in darkness, in one location, lending it a stage-like quality, to the phenomenal black and white cinematography that makes the viewer almost crave to find the grey between the characters who are – no pun intended – so black and white, the technical precision of the film deserves due credit. That being said, the technical prowess does not always enhance Malcolm and Marie. As the audience, we are still more often than not left frustrated by the characters’ volatile states of mind, and for the average non-cinephile watcher it is understandable that the film may seem cluttered with too much emotion and repetitive drama.

However, when given thought, and pulling from one of Malcolm’s monologues; perhaps that is the point. In the beginning we are made aware that this film is not a political statement, it is art that exists for the audience to feel and interpret instead of trying to understand what the director may have intended. Alas, because of the rollercoaster ride that the film is, that is surprisingly what happens. We are made to feel a plethora of frustrating and disorienting things instead of trying to decipher the meaning behind everything. So, yes, the film does not make us feel good, but it’s not supposed to. And the characters, though they are not remotely likable, have emotions which are very real and recognisable. Maybe this effect stems from the fact that neither Malcolm nor Marie are real, but are exactly what we view them as: toxic characters, if not caricatures of toxic characters. But even if they were to be a real couple having arguments through extended monologues, the truth is, the film is not a depiction of reality. Said simply, the film is but an amalgam of real emotion and thoughts sometimes coherently displayed and other times chaotically so.

Ultimately, I would say that Malcolm and Marie is an experimental film that both succeeds and fails. While it is art that undeniably opens itself up to debate and interpretation, with visceral visuals and at times impressively executed acting, the characters remain largely embittering. The film leaves us feeling all over the place by pushing the envelope too much on needing to be ‘art’. Despite there being a method to the madness that unfolds, Malcolm and Marie falls short in being the work of “art” it hoped to be. It goes beyond “telling and not showing” and leaves us, at the end, with a cultural output that unfortunately “shouts, not shows” a bit too brazenly.