The Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme runs from February 19th until March 10th, and this year focuses on the theme of ‘This is My Place’, celebrating Japanese cinema with an inspiring selection of new-releases.

Editor-in-chief Tomi Haffety reviews a drama addressing gender inequalities in Japanese marriage.

After being struck by the poignancy of Dear Etranger at JFTFP 2019, I had high hopes for Mishima’s second entry to the festival, Shape of Red. Portraying themes of family breakdown and an exploration into Japanese societal expectations, Mishima does well to hold a critical lens to the gender standards and traditionally limited roles of women in Japan. Living an enviable life, Toko Muranushi (Kaho Indō) seems somewhat trapped in her role as wife to a successful but dismissive husband, Shin (Shōtarō Mamiya), and mother to a young child. It is only through the rekindling of an old, complicated romance that Toko starts to question her desires and responsibilities.

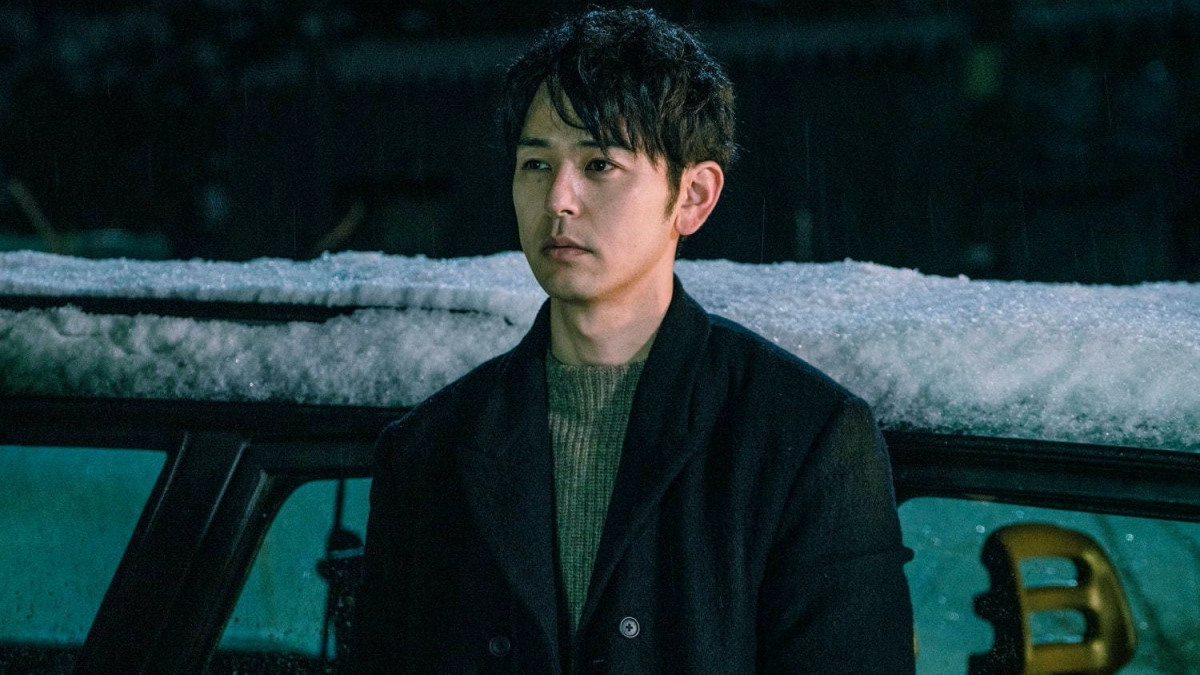

Beginning the film with the atmosphere of a recently-occurred tragedy, a cold blue hue reflected on thick snow sets the film up to be an uncomfortable and often harsh watch. This sharpness is immediately contrasted with a scene of sunlight and a warm breeze drifting through the trees as Toko arrives to pick up her daughter, Midori (which means ‘green’ and seems to symbolise the purity of her childhood). Nature within cities, especially heavily urban cities like Tokyo, appears to exude more power and meaning than when seen in abundance in a non-urban environment. The trees are a compelling indication of the solitude that Toko feels. Living in her gaudy home while pandering to her stern mother-in-law and adhering to the unspoken gender rules of Japanese marriage, she feels lonely and unappreciated. At a business gathering of her husband’s, Toko is left wandering alone the grounds of the hotel where she is staying until her aimlessness culminates in a deliberately abrupt silence as she recognises the face of someone from her past.

Kurata (Satoshi Tsumabaki) is an aloof character who shares a complex but passionate history with Toko. Their relationship begins again ten years after they left it, with Kurata encouraging her to take a job at his architectural firm and find new direction outside of the home. In a sombre plot twist, Kurata’s struggle with terminal cancer gives a new layer to the already convoluted love affair. An intense sex scene, presented in contrast to an earlier scene of awkward and jilted intimacy between Toko and Shin, proves that with Kurata, Toko feels empowered and appreciated. However, although primarily depicted as an uncaring and selfish husband, it is Shin who offers the most character development. By the end of the film, I found myself pitying Shin and questioning whether he held bad intentions for Toko or their marriage. Growing up in a conservative family and heralded as the polished son by his domineering parents, Shin himself is a product of the societal expectations that create the voids of communication and cooperation between married couples in Japan.

Adapted from Rio Shimamoto’s 2014 novel Red, the overarching storyline is modern and compelling, acting as a powerful protest to the narrow idea that women must choose between family and career. In masterful shots using a shaking camera to depict Toko as she calls her husband from a stranded telephone box in Niigata and expresses her frustrations and sadness at her feelings towards him, Mishima succeeds in portraying the inner-conflict of a woman who married due to societal expectation but lacks emotional connection to her family. However, the unique shots and scenes of expert technicalities, such as the use of bold colours that embody the characters’ feelings, are lost within the overlapping timelines and locations that disappointingly create too much of a distraction from the main storyline.

The film is constantly and abruptly changing locations between Tokyo and a snowy Niigata, where Toko and Kurata visit on a business trip, making the timeline of events confusing. The dots don’t connect until the last quarter of the film, by which time there are already too many loose plot points and the strength that Shape of Red began with has unraveled into a loosely woven story. Characters are introduced with inadequate detail, and Toko’s fleeting outing with another workplace friend who expresses an interest in her is then left completely unexplored until an eventual forced conclusion. Additionally, a New Year’s Day visit from Toko’s mother is crammed into the story to add another perspective, but her screen time is awkward and contributes very little to the overall plot. Despite the small main cast, none of the characters aside from Toko are explored enough to create an emotional connection to them and thus, Shape of Red presents a confusing timeline of dramatic but underdeveloped events. At the end of the two-hour feature I was left with the feeling that there was something missing, but exactly what this is, is hard to pinpoint.

Holding a mirror up to the gender roles within a highly divisive culture, Shape of Red is an accurate depiction of the struggles faced by many women whose options have been limited. Mishima herself is a fierce critic of this aspect of Japanese life. Articulating this, she argues that ‘more Japanese women should have their own individual standards of what happiness is.’ Along this vein, she has succeeded in portraying a woman exploring her own desires and embarking on her own journey of identity. Nonetheless, I failed to grasp the point of focussing so strongly on the dichotomies between Toko’s life in Tokyo and her experiences in Niigata. It became difficult to understand the point of many of the extra avenues given an inadequate amount of narrative time, and the final product is an altogether weakly constructed story.