Emily Chen reviews the highly-anticipated return of Miyazaki to the Ghibli animated universe.

![]() Hopeful surrealist impressionism

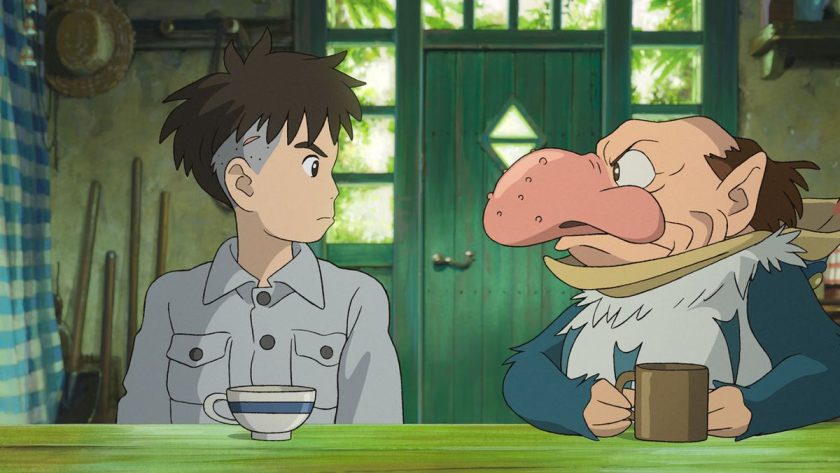

Hopeful surrealist impressionism

![]() Kimchi Nabe – the spice will make your tongue ache at first, then an unlimited number of ingredients will hit you until you leave this hotpot meal with your soul intimately warmed.

Kimchi Nabe – the spice will make your tongue ache at first, then an unlimited number of ingredients will hit you until you leave this hotpot meal with your soul intimately warmed. ![]() Anyone who wants to be taken on a vibrant and delicate ride across the spectrum of human emotion.

Anyone who wants to be taken on a vibrant and delicate ride across the spectrum of human emotion.

“Still, I can become a good person. I can become a good person and create one good person for the world. And I think that if I can just do that, then I might become a person who can create even more than that.”

― Genzaburo Yoshino, How Do You Live?

‘The Boy and The Heron’ paints an enigmatic portrait of a boy’s psyche charred by grief and grounded by love, in the midst of war, chaos and fear. Yet ultimately, Miyazaki’s usual optimism elevates the movie from darkness to hopeful radiance.

The film begins in media res, with Mahito swept up into the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. Upon the bombing of his mother’s hospital, pre-emptive grief blends Mahito’s reality and dreams. Air-raid sirens whistle between discordance and consonance, almost forming ethereal bright chords. Panicking crowds morph into globules of black, sluggishly dragging his chase towards the hospital and sweeping him up. Mahito’s experience directly parallels that of Miyazaki’s earliest memories—evacuating war-torn cities in Japan. While Miyazaki’s mother did not succumb to air raids, Miyazaki too had to grapple with the notion of his mother’s death as he witnessed her battle with tuberculosis. These intimate recollections serve as the springboard in which Miyazaki unfolds the story.

After Himi’s passing, Mahito’s father Shoichi remarries his late wife’s sister, Natsuko, who is said to be the spitting image of beautiful Himi. This introduces subtle but ever-present Freudian undertones, trapping Mahito in an Oedipus complex as he actively distances himself away from his stepmother. Facing Mahito’s rejection, Natsuko withdraws into herself; we cannot help but feel touched by her unconditional love towards Mahito despite his distance, all while she grapples with the uncertainty of her pregnancy. Meanwhile, Mahito’s emotional world is thrown into disarray; Miyazaki displays his grief in a multitude of ways, from his haunting nightmares of Himi screaming helplessly while engulfed in flames, to the silence and stillness of Mahito’s exhaustion. With grief underlining much of Mahito’s new life, Miyazaki portrays it to be an inexorable part of the human condition, a lesson we learn empathetically slowly throughout the movie. This motif is embodied in the Grey Heron, which symbolises death and rebirth in Japanese culture. The Heron swoops indoors for the first time when Mahito and his father move into Natsuko’s countryside home, and continues to pester the boy from then on. It is also the Heron who plays to Mahito’s grief, luring him into a fantastical world with the promise that Himi is still alive in it. When Natsuko disappears mysteriously into it one day, Mahito is determined to search for both his mother and stepmother.

And with Mahito, we are thrust into the absurd vividness of a limitless, impressionistic realm. This world suggests utopian hope, highlighted by the lush greenery of its garden grounds (not unlike that of the Garden of Eden). Alas, it too is streaked with pain and malice; frame after frame, I found myself flung from the man-eating gluttony of the Parakeet troops to the ominous black blotches of faceless boat rowers to the heartless avarice of pelicans feeding on adorable Warawara. While critics deride the fantasy world’s disjointed messiness, I found that it was a perfect parallel to Mahito’s inner psyche; dealing with grief is a non-linear process, and this escape allowed Mahito to grapple with his feelings from a healthy distance.

In this other world, Himi appears as her younger self. Instead of succumbing to flames, she embraces them and uses her pyrokinetic powers to protect the vulnerable. I could not help but cling to this hopeful image with Mahito—perhaps in an alternative universe, her strength prevails over the debilitating forces of fire, and perhaps she is still alive. Yet this optimism is balanced delicately; we also learn later on from a dying pelican that it feeds on the squishy white puffballs that are the Warawara for survival, rather than malice. And when Mahito silently buries its body, our hearts ache for him, because he begins to accept the painful truth that death is a natural counterpart to life.

This tension is further springboarded when we are introduced to the maker of this other-world, Natsuko’s granduncle. He requests that Mahito, possessing the power of his bloodline, succeed him as the wizard of this world by repeatedly stacking stone toy blocks to maintain their balance. Mahito first hesitates, noticing that the blocks are infused with malice. The wizard implores him once again, this time offering replacement blocks free of malice for Mahito. While the prospect of building his own world free of loss and grief entices him, he acknowledges that he too is sinful and thus cannot hope to run away from imperfection. Instead, I felt intimately inspired as I watched him choose to return to a flawed but real world, marred by pain but grounded by familial love. Even as he arrives in the real world, our hearts soften when we see him longing to return back, as he clutches onto the building blocks he has brought home accidentally. The Heron urges him to forget his fantasy; with this cultural symbol of grief turning into a source of strength and companionship, we heave a sigh of relief that Mahito has managed to move on to a stronger place. These quandaries are what make Mahito such a character we cannot help but come to love, because he deals with them in a gently candid manner rooted in silent strength. Miyazaki, once again, has constructed a beautifully layered and complex character.

Before returning from the other world, he too grows to accept his stepmother. He bursts into the forbidden delivery room that Natsuko is lying in. As slits of paper cut and burn into the approaching Mahito, Natsuko rebuffs him. While this can be seen as an outburst of repressed anger towards Mahito’s rejection, the optimism laced in previous scenes leads us to believe that perhaps she is pushing him away to prevent him from getting hurt. Mahito chooses to believe the latter and finally acknowledges her as his mother in an emotionally-stirring scene. Here, Miyazaki ensures that despite all of Mahito’s flaws, his strength triumphs and allows him to be reborn as a much more inspirational force, one who always returns to love.

Mahito’s character that bends towards goodness is mirrored in Hisaishi’s music, in the recurring melodic themes consisting of bright, slow chords, lined by luminous string melodies. Despite the lofty themes, I never felt lethargic throughout. The balance between despair and hope is sensitively navigated, and Miyazaki skillfully interjects heavy moments with comedic relief (in a movie flurried by flocks of birds, their droppings definitely have to be featured). We leave the cinema with an illuminating lightness, touched immensely by the love and optimism that perseveres despite the pain and loss.