The London Film Festival returned this past October featuring a wide array of British, Hollywood and International cinema.

Aryan Taqueer reviews David Fincher’s The Killer. It is the director’s second feature film with Netflix, following his surprising turn with 2020’s biopic Mank, and a return to his distinctive slick, nihilist and violent style.

Early on in Las Von Trier’s sinewy slaughter epic The House that Jack Built, our titular architect Jack (Matt Dillon) decides to start a family- quite the dramatic settling down for a man with a 12 year career as a serial killer. Of course, the manner in which he decides to construct his ideal family picnic is perhaps a little convoluted, much like the rituals of transcendental agony that Von Trier places his own characters through, as he abducts his girlfriend and her children in a white van and expects them to simply adopt the roles that he has imposed. They play the part well enough. Yet, no matter how well they maintain the diorama of a loving family, that Jack is so insistent on, their conversations are merely empty space- a stream of garbled small talk that only delays the inevitable. Yet, as shown when Jack kills his girlfriend’s two young children and forces her to continue the picnic with their corpses, Jack’s true fantasies take root through fear, and feeding it off the many victims he harvests throughout the course of the film.

In David Fincher’s latest deliberation upon the crevices between normalcy and the mechanisms individuals develop to fill them, the fantasies espoused in von Trier’s film are here mere procedure. They are parceled by the clocking in and clocking out of a freelance contract, and the grating mundanity that accompanies the 9-to-5 of our unnamed assassin’s daily routine. Fincher’s penchant for a distinctly Gen-X brand of cynicism and general moral turpitude- characterized by a knowing distrust of multinational corporations and nonchalance towards the ethics of homicide- asserts itself with greater prominence here than in any of his filmography since Se7en. This, in no small part, is owed to the fact that The Killer is his first collaboration with screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker since 1995- something that swiftly becomes evident through The Killer’s internal monologue, which almost always undercuts tense sequences of planning and executing assassinations with sardonic (though not necessarily witty) interludes. The closest analogue to the interiority created by this running commentary may be Fight Club, but Fincher has clearly grown either jaded or at least more cognizant of how the distinctly juvenile fantasies embodied by much of his 90s oeuvre no longer bear such anti-establishment or countercultural weight. Instead, much of The Killer’s musings on the morality (or lack thereof) of his line of work are at constant odds with how his carefully planned assassinations actually proceed. “I. Don’t. Give. A. Fuck” is one of his mantras, yet in the film’s calculatedly distended opening sequence- what would otherwise be a swift dispatching of a financier in a Parisian high-rise- there exists an overwhelming, manic paranoia expressed in both The Killer’s monologues and pre-assassination routines. Amongst the most amusing of these is a proclivity for the catalogue of The Smiths, which foregrounds every sequence of execution and escape with a certain musicality. That musicality is embodied in the rhythm of the edit, which strips away the procedural to its barest parts- that is, procedure. Instead of the conspiratorial machinations of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo or Gone Girl, The Killer unfolds through misanthropic rituals and rules, created to provide some semblance of order in a life defined by wanton bloodshed.

Though the film grapples with its graphic novel origins in the form of a spiral of espionage that is more Mark Millar than Le Carre, there exists a frustration that only grows more aggravating the longer The Killer goes without fulfilling its titular promise. For something touted as Fincher’s first foray into action, The Killer only sparingly dabbles in the recognizable and vicarious pleasures afforded by the genre. When it does, the director’s maniacal attention to the geography of space wins out over the movements of the titular assassin. During a dimly-lit brawl with a muscle-bound hitman inside a flimsy Floridian condo, the kineticism of procedure that characterizes The Killer’s movement throughout featureless transitory spaces- airports, rented storage facilities and abandoned WeWork offices- is splintered into manic retreat. No amount of self-mythologising on the part of Fassbender’s droll hitman can resolve the contradictions between the juiced-up meathead bursting through drywall and himself. Much of the tension that propels the film itself stems from the dissonance between The Killer’s self-professed mantras of professionalism, and the bloody trail of missteps and misperceptions that results in the film’s rising body count. For a genre as steeped in notions of absolute precision and self-effacement as the hitman film, The Killer’s refutation of these rules is at a remarkable and often unsettling disconnect from it, just as it is simultaneously in seamless sync with the interiority of its fickle and unsteady protagonist. Though the work of both Jean-Pierre Melville and Seijun Suzuki are invoked throughout (not least in the film’s attention to the slickness of mundane procedure), Fincher and cinematographer Eric Messerschmidt (a central collaborator of his late style) craft something closer to Soderbergh’s Haywire. Both are thrillers so stripped of the very intrigue, or excitement, that defines the genre that the myriad processes and adjustments that allow for a netherworld of contract killers paid for by billionaires, banal as they may be, to exist. It’s a quality that recalls the director’s earliest work on music videos like the one for Nine Inch Nails’ Only, which- as with The Killer– acts as a near-seamless synchronization of image and sound.

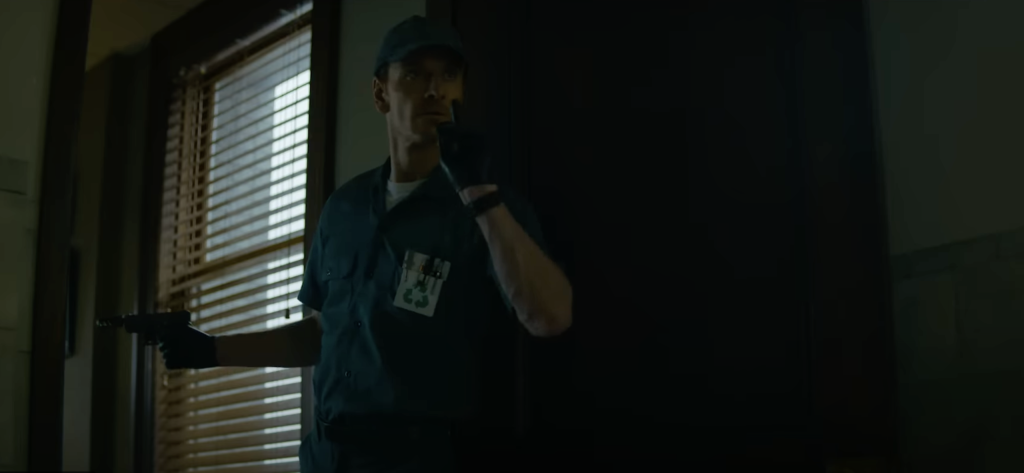

Style, though more than enough of a justification on its own, is far from the only thing on the mind of both Fincher and his sociopathic McGriddle-eating avatar. Corporate insignias are littered throughout the transient spaces of The Killer, and in a dryly unsubtle touch on Fincher’s part, are the unassuming fronts for a global network of blood money and even bloodier contracts. Bleary-eyed and bored, our introduction to our emissary for this world is him sitting next to a space heater in an abandoned WeWork office. In Fight Club the recurring appearance of Starbucks coffee cups suggested a permeating of consumerism from the sphere of the corporate into the sphere of the personal- an infection of capital, in more blithe terms. Yet 24 years later, corporatism manifests not as universal symbols of commerce but as rhythm of everyday movement- contactless payments, public transport passes saved on smartphones and Amazon deliveries are the latest advancements in the encroaching on personal privacy, and independence from technologies produced and controlled by multinational corporations, and yet they are all avenues that The Killer exploits with ease. Indeed, there’s a faint air of reactionary libertarianism to the assassin’s various diatribes which resembles modern day social media demagogues, more colloquially the “grindset”, who position themselves as defenders of a supposed masculine protestant work ethic. “Anticipate, don’t improvise. Empathy is weakness. This is what it takes if you want to succeed” says the expendable worker, subject to the whims of employers who would see him dead if he fails to deliver. Even Fassbender’s positioning in the frame, as he cowers and crouches in the darkness of indistinct white vans and in dimly lit condos, suggests a contradiction between the powerful identity he purports to possess and the fragile one that he embodies.

Yet, when the film departs from the well-oiled engine of his perspective as a professional putting in his two-week notice (aided and abetted by Amazon and Postmates as conduits) it becomes swiftly and brutally evident how much the subjectivity of Fincher’s direction obscures from us. The most disconcerting manifestation of this is a shot of a victim’s hands bound together, clawing out in agony like one of the chest-erupting Xenomorphs from Fincher’s Alien3 as she screams for someone to save her. In a film hinged so securely upon the twitches of Michael Fassbender’s face and the emotional disguises it dons, such departures represent a recontextualization of the Fincher oeuvre- the serial killers of Se7en and Zodiac, leaving a trail of corpses and viscera and giving way to a serial killer who covers his tracks well enough to be able to denote himself a mere agent of neoliberal capitalism. In a similar vein, the figure of the tech billionaire- who in retrospect was far too humanized in The Social Network – is an oblivious, little man entirely unprepared for the consequences of his whims . Far from the romantic archetype of the Camusian stranger expressed in Melville’s Le Samouraï and Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control, the contract killer here is a ruthless pragmatist who quotes Aleister Crowley without knowing who he is, and executes women as dispassionately as he does men. As with Gone Girl, however, there exists the compelling contradiction between narrative and interiority. The Killer slaughters without discernment, and yet the pile of bodies that stack up as he makes his way through a hierarchy of power represent an oddly hopeful, if embittered, tale of a worker confronting his expendability and deciding to reject it by killing for revenge rather than a payment. Whilst the motivations may have changed, however, the methods remain as efficient as ever- an ethos that applies to Fincher as much as it does to The Killer, and one that after the somewhat puzzling, if not disposable, Mank allows a professional to do what he does best.