Bryn Chiappe tackles the impact of the Dogme 95 manifesto and its lasting legacy on cinema.

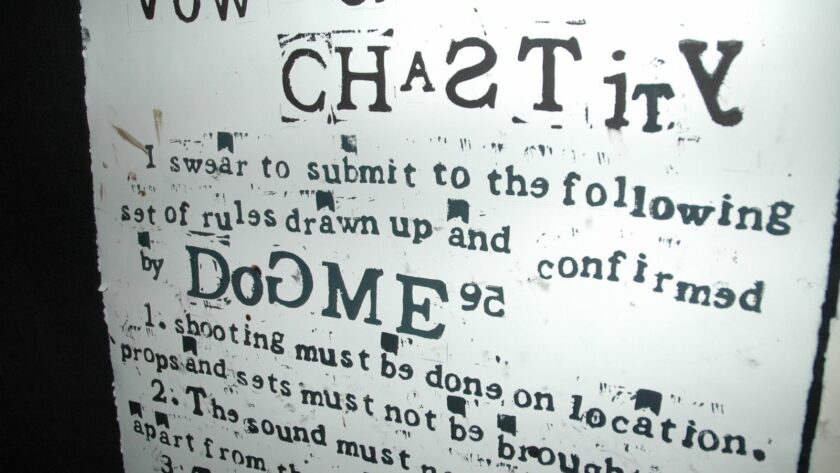

THE DOGME 95 VOW OF CHASTITY

I swear to submit to the following set of rules set up and confirmed by DOGME 95:

- Shooting must be done on location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found).

- The sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa. (Music must not be used unless it occurs where the scene is being shot.)

- The camera must be hand-held. Any movement or immobility attainable in the hand is permitted.

- The film must be in color. Special lighting is not acceptable. (If there is too little light for exposure the scene must be cut or a single lamp be attached to the camera.)

- Optical work and filters are forbidden.

- The film must not contain superficial action. (Murders, weapons, etc. must not occur.)

- Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden. (That is to say that the film takes place here and now.)

- Genre movies are not acceptable.

- The film format must be Academy 35 mm.

- The director must not be credited.

Furthermore I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a “work”, as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.

Thus I make my VOW OF CHASTITY.

Copenhagen, Monday 13 March 1995

On behalf of DOGME 95

Lars von Trier – Thomas Vinterberg

It’s been twenty-five years since Lars von Trier took to the stage of the Paris Odeon cinema and introduced his brainchild, the Dogme 95 manifesto, to the world. The manner of delivery was far from meek. After reading out the ‘Vow of Chastity’ and manifesto, von Trier threw red leaflets containing the manuscript into the crowd, and declared that he could say no more on the matter at that moment, before immediately proceeding to leave the theatre. Make what you will of von Trier; to consider him a pretentious egomaniac would be a well-substantiated perspective, yet viewing him as a cynical, brilliant visionary is evidentially-reasonable also. A quarter of a century on from his antics in Paris, it’s undeniable that regardless of where you sit on the von Trier fence, Dogme was deeply significant in its ability to spark debate and make filmmakers question their approach. And yet, can it be correct to say that merely creating a new conversation is the marker of a successful manifesto? Dogme is canonical in the realm of film studies seminars, but did it change the industry? Perhaps the key to answering that question is another one – did it want to?

In evaluating Dogme as a manifesto, it would be sensible to begin by establishing what a manifesto is and what function it serves. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as ‘a written statement in which a group of people explain their beliefs and aims, especially one published by a political party to say what they will do if they win an election.’ The beliefs and aims of a manifesto are its diagnosis of the issues in the world around it, and its offered solutions to said problems. It’s interesting to see how few manifestos manage to make the leap from the former to the latter in a convincing fashion (looking at you, Marx and Engels). In order to assume the position of teacher and messiah (as one must when writing such an instructional text), we can see across the manifestos of modernity that a certain tone is deployed – one that is provocative, antagonistic and inherently undialectical. This usually goes hand-in-hand with the fact that a metanarrative is being used as the answer to whatever problems are in question.

A manifesto is always a product of, and a statement on, its precise environment, a rule to which Dogme is no exception. The fact of this grounding in a contextual instant is usually the downfall of all manifestos, be they artistic or political, given that its assessments and teachings naturally tend toward becoming redundant as time passes. Some have tried to update manifestos in order to tailor them to a changing world, with notable examples being Andre Breton’s continual reworking of his surrealist manifestos, and Sergei Eisenstein doing away with his guiding principles after intellectual montage and Lenin were replaced by Socialist Realism and Stalin. Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg allowed Dogme 95 to remain an artefact of 1995, but I’ll get onto that later.

The context of Dogme was one of a globalised world in which Denmark was a blip on the international cinema map, and in which rapid technological developments were increasing the ease of the filmmaking process, while stifling the creativity and experimentation of those working within the industry. There’s a useful quote from the manifesto that explains this feeling:

Today a technological storm is raging, the result of which will be the ultimate democratisation of the cinema. For the first time anyone can make movies. But the more accessible the media becomes, the more important the avant-garde. It is no accident that the phrase “avant-garde” has military connotations. Discipline is the answer… we must put our films into uniform, because the individual film will be decadent by definition!

This collectivist sentiment identifies the issue of repressive orthodoxies and traditionalist approaches to the the cinematic medium, but it does so in a way that transcends the gimmicks of low-budget filmmaking and arthouse cinema. By encouraging a critical perspective of the structures of conformity and the opportunities presented by cheaper, more efficient cameras and equipment, Dogme manages to address the issue of an art saturated by formula, idealistically critiquing the present, and proposing a pragmatic solution for the future. The manifesto is under no illusion that their group were the first to attempt a cinematic revolution.

In evaluating its place in film history, Dogme challenges the pedestal upon which the French New Wave was placed, and questions why it ‘proved to be a ripple that washed ashore and turned to muck.’ At least this is how it appears at surface level, as in fact, there is a strong argument for Dogme 95 as the natural progression from, and successor to, the work of Godard & co. The degree to which Dogme was facilitated by the French New Wave, borne out of its wake, is well explained by Christian Jensen, who writes in Politiken that ‘Dogme resembles a definitive rebellion against, and a ‘father killing’ of, the French New Wave directors […] but it is in reality an homage to them and their great contribution to a modern breakthrough for film.’ Dogme was not the first, and certainly will not be the last organised movement within the film industry to display such clear, concise methods for resolving stagnation, whether or not they present the masses with a manifesto.

By 1995, the idea of the art manifesto was nothing new. By the early 1910s and 20s, Italian Futurists, German Expressionists, and French Dadaists and Surrealists were all producing manifestos, stating their political, aesthetic, and philosophical principles. In most cases, these texts were calls to revolution. Even a near-identical diagnosis of cinema’s fundamental problems can be seen in earlier manifestos, such as in this quote from members of the ‘New American Cinema’ written in the summer of 1961, thirty-four years before von Trier threw his leaflets over a Parisian crowd:

The official cinema all over the world is running out of breath. It is morally corrupt, aesthetically obsolete, thematically superficial, temperamentally boring. Even the seemingly worthwhile films, those that lay claim to high moral and aesthetic standards and have been accepted as such by critics and the public alike, reveal the decay of the Product Film. The very slickness of their execution has become a perversion covering the falsity of their themes

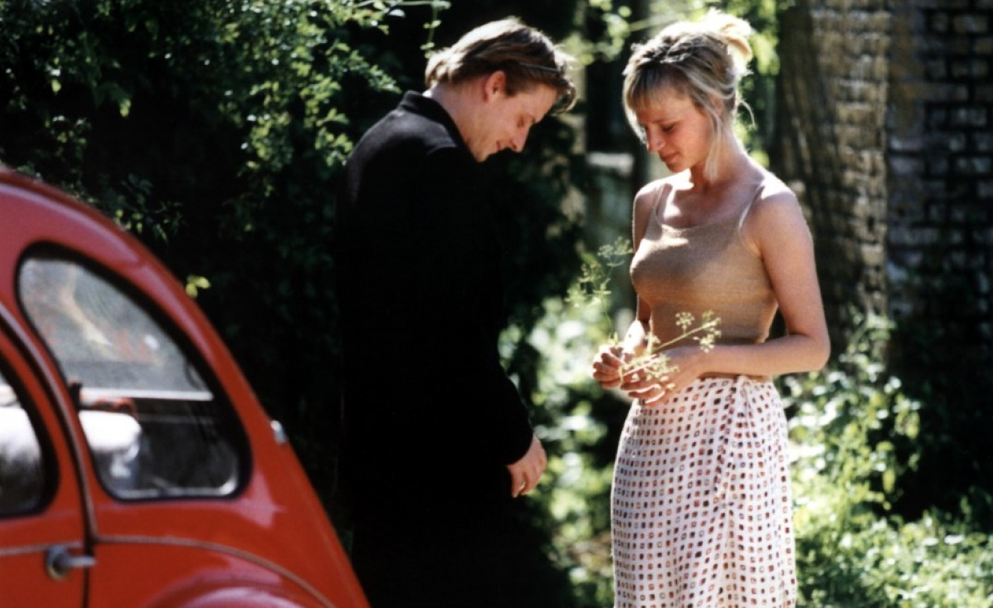

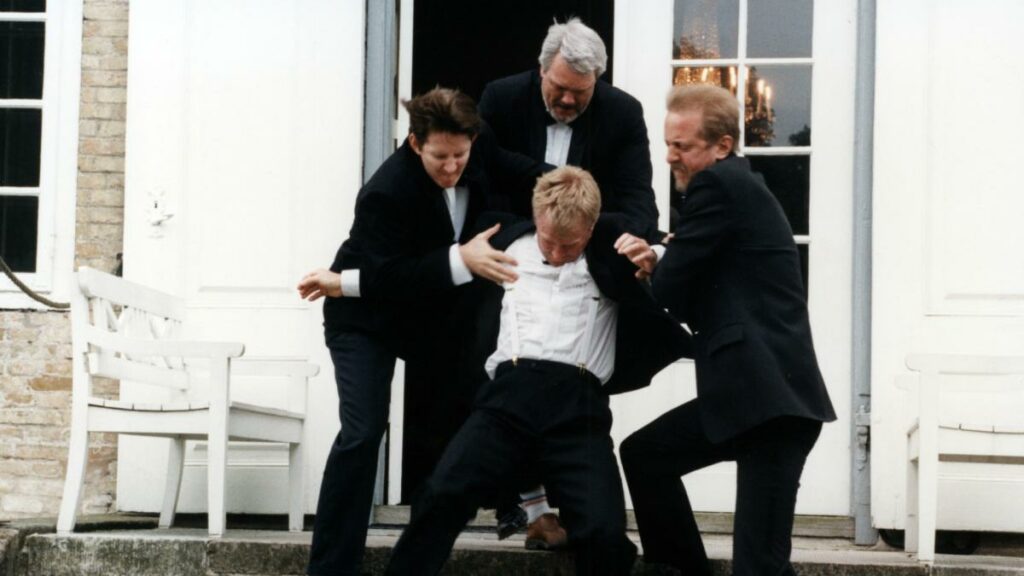

In light of this history, it’s more than reasonable to ask why Dogme took the film world by storm in the way it did, and why it’s the sort of thing students write about for their film society’s blog twenty-five years later. A factor in this is certainly the calibre of work produced by the Dogme directors. Dogma #1, Festen, won the Jury Prize at Cannes in 1995, and Dogma #3, Mifune, won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 1999. Many a director can invent an experimental concept for how to shoot a film, but it is rarer still to see these concepts used to tell genuinely brilliant stories, and focusing on bringing out the best in actors as opposed to revelling in the cult of the director. However, I will give Dogme what it demanded and discuss the movement in a pluralist sense. “The individual film will be decadent” after all.

What separates Dogme from other filmmaking manifestos is perhaps that the rules it suggests are centred on form rather than content, treating the two as completely detached entities. Arguably one rule out of the ten defies this thesis: rule six states that ‘the film must not contain superficial action. (Murders, weapons, etc., must not occur.)’ While this unarguably creates a restriction on the possible plot of a Dogme film, it is motivated by a frustration at scripts relying on cheap, easy tropes that detract from a pure focus on the story itself, and therefore sits neatly alongside the other rules in their effort to stimulate plots with powerful content rather than to dictate the themes and messages of the films.

The manifesto’s concern with form gives it a level of desirability to filmmakers far greater than many other film manifestos and movements. While sensibility and taste for certain thematic values vary between individuals and time periods, the invitation to work within self-enforced formalistic parameters leaves the onus on the specific filmmaker to tell the story they want to tell. The universality and immortality of the proposals are upheld by the avoidance of a metanarrative surrounding story. It is also crucial to bear in mind that the manifesto’s limitations for formal experimentation frame it very much as a proposal for exactly that. It does not state that all films must be Dogme films, nor that all films should be, but provides an avenue for shaking oneself free of tradition and discovering (or rediscovering) what it means to be avant-garde.

The “Godfather of Dogme”, manuscripts studies professor Mogens Rukov, has stated that no film “wave” ever lasts longer than eight years. At the time of writing, thirty-five Dogme films have been released. The last one was Cosi x Caso in 2004, nine years on from the manifesto. From this, it would appear that Rukov’s statement has held true. However, to say that films made under the rules of the manifesto dying out equates to the influence of the text dying out would be a superficial understanding of von Trier and Vinterberg’s intentions. There is great validity to the claim that the Dogme 95 manifesto was a joke. Vinterberg has stated that “Dogme is in the area between a very solemn thing and deep irony.” The language of the manifesto is of such contrived socialist phraseology that it reveals itself to be a self-conscious satirisation of the attitude von Trier became familiar with during his youth in the Communist Party (his mother’s influence). Whilst he abandoned the ideology in his university years, von Trier deployed the language and attitude for an effect that is so overly dramatic it becomes comedic. The fundamental irony of the text, and one that it is entirely aware of, is the suggestion that the way to battle formulas and traditions is with a set of rigid, uncompromising laws to be faithfully obeyed.

The Dogme directors themselves quickly moved away from making films that followed the manifesto, and in doing so exposed the fact that it was less a manifesto than an expression of discontent. It is hard to truly tell what level of irony Vinterberg was operating on when he was asked why he didn’t make a Dogme film after Festen, and replied that ‘the fine thing about Dogme is to create renewal, and to do another Dogme film right after would be creating another convention, which would be very oppressive.’ It would be equally valid (and not necessarily mutually exclusive with the joke theory) to argue that while the specifics of Dogme 95 were abandoned, the spirit of it was retained. Lars von Trier’s work has followed a pattern of self-imposed rules and restrictions across his career (Dogville being the most obvious example), even if they have not always been the rules of the Dogme manifesto.

Joke or not, von Trier and Vinterberg wrote their manifesto to challenge the orthodoxy on the institutional features of small-nation filmmaking. It had far more to do with questioning the relationship between film, minority cultures, and globalisation than it did to conforming to a prescribed set of rules. Although it is not possible to concretely define the effect of Dogme 95, it is certainly the case that regardless of its intention, it gave validity to low-budget filmmaking, and acted as one of the most successful publicity stunts in film history in terms of its impact on von Trier and Vinterberg’s careers. Dogme 95 was directed at avant-garde filmmakers and had little interest in their budgets. It certainly ignited discourse on the importance of experimentation, serving a purpose for the directors who followed it, and undoubtedly challenged others to be bold and question their methods. It remains an example of the power of breaking the rules and challenging those who dogmatically uphold conventions. Ironic. But perhaps that’s the point.