Natalie Wooding reviews Federico Fellini’s iconic film, in celebration of its 60th anniversary.

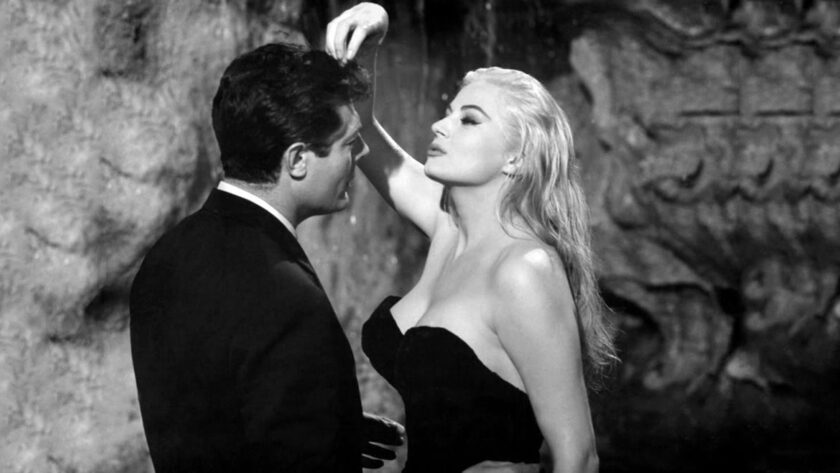

La Dolce Vita is a party. It is a world of glamour and sophistication inhabited by larger than life characters, ranging from the mass of scrambling paparazzi (a term this film coined, from the character Paparazzo) jumping from walls and tumbling over each other in an effort to get the most scandalous shot, to the glamorous Swedish movie star, gliding around Rome at 3am in a full length ball gown topped with, instead of a hat, a kitten she has found and picked up along the way. The film follows Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni), a jaded veteran reporter as he chases celebrity after celebrity through party after party, each one outdoing the next in decadent celebration.

Fellini’s hyperbolic style is often contrasted with the Italian neorealist movement that was popular when he began his cinematic career. With the aim of faithfully depicting the everyday lives of Italians suffering after the war, neorealist directors sought a sombre and objective style that distanced itself from Hollywood artifice and glamour as much as possible. In the words of Zavattini, a leading theorist and neorealist screenwriter, the aim of cinema was to represent “living social facts.” Films such as Ladri di biciclette, which depicts the struggle of a father trying to raise his son to be morally just in an unjust world, are heart breaking in their honesty and immensely powerful in their restraint.

By the end of the 1950s, Italy’s economy was thriving, and flourishing “made in Italy” design was quickly becoming world-renowned. In La Dolce Vita, life is an exciting celebration of opulence and entertainment, as the title affirms: ‘Life is Sweet’. In this world of glamourous parties, Fellini only refers to his neorealist forefathers playfully, with a knowing wink and a smile; when the audience are led down a series of broken steps into a flooded basement of a war torn building, the scene is not dire but comical – the professional prostitute who owns the house is swearing loudly and the two people she is leading fall into each other’s arms in a torrid affair. “Credi che il neorealismo italiano sia vivo o morto?” (Do you think Italian neorealism is alive or dead?) is one of the unanswered questions thrown from a horde of reporters to the glamorous actress Sylvia (Anita Ekberg) amongst “Do you practice yoga?” and “Do you like men with beards?”

Where neorealism offers sombre observation, Fellini uses all the tools of cinema at his disposal to offer scene after scene of beautiful, sensual and hypnotic cinematography. It is impossible to not get swept up in Fellini’s parties; to try to tear your eyes from the screen as the camera sways rhythmically, following Sylvia’s dancing to Nino Rota’s upbeat jazz soundtrack, leading a line of dancers as she sweeps across the screen; to not be enraptured watching Marcello decorate a drunken young show girl with feathers, the down from the ripped cushion swirling slowly around him.

La Dolce Vita is a film that does not shy away from the make-believe of cinema – it happily embraces spectacle to the point of being carnivalesque. The sets are vast and opulent; the costumes are heaving with feathers, adorned with glittering necklines and glimpsed suspenders between split skirts. Be they paparazzi, celebrities or wannabes, Fellini’s characters look up to professional actors, dancers, party-throwers, all happily immersed in the fairy-tale mythologizing of Hollywood. In the world of La Dolce Vita, everything is pretend and everything is wonderful.

Where Fellini differs from Hollywood’s superficial indulgence in visual glamour and movie star celebration is in the thread of existential anxiety he weaves throughout the film, an anxiety that eventually constricts every single character. La Dolce Vita follows characters’ drinking and sexual escapades without judgement, allowing the existential dread to manifest itself naturally through small details. In a hilariously chaotic scene where crowds of Italians run around chasing a miracle sighting of the Madonna, Marcello’s long-suffering fiancée Emma confronts an old woman who does not believe the miracle matters. “Why would you say such a thing?” presses Emma, who has just prayed that Marcello will finally marry her. By the time the most shocking and poignant scene of the film transforms La Dolce Vita into an ironic tragicomedy, we are already resigned to watching the characters entangle themselves in their superficially happy but empty lives. Fellini’s opulence and his cheeky joie de vivre conceal an underlying melancholy; for all their celebrating and elaborate costumes, all of the characters ultimately find themselves uncertain, lost and alone.

Fellini’s masterpiece is both a sumptuous visual feast and a social commentary on the post-war culture of excess. Perhaps, in his quiet observing and capturing of a generation’s existential ennui, he remains a neorealist after all.

You can catch La Dolce Vita at the BFI now, and the film is available to buy or rent online or in stores. Check out the trailer below: