George Moore-Chadwick reviews Wes Anderson’s highly anticipated return to animation.

The opening of Isle of Dogs informs us the Japanese spoken in the film will not be translated, unless by a TV interpreter or a foreign exchange student. All dog barks will be translated into english. Wes Anderson has finally reached peak Wes Anderson. This is both a good and bad thing, because Anderson is one of the most visually astounding and idiosyncratic filmmakers alive, but his films often fall short of true greatness because of it.

Anderson’s best film is his first, the criminally undervalued – and Martin Scorsese favourite – Bottle Rocket (1996). Here he demonstrated the magnificent visual style and quirky humour that have come to define him, but not at the expense of characters or themes. His style soon developed with brilliant Rushmore (1998) and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), which consist of medium close-ups, perfect symmetry, a lurid colour scheme supported by a very ornamental production design, an eclectic soundtrack and offbeat, super-fast dialogue. His last film, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), broke from relying on the die-hard fanbase he has built over the years and became a huge success, winning multiple Academy Awards. It was a brilliant film in almost every way, because Anderson’s instantly identifiable style, penchant for metafiction and self-reference were backed up by a genuinely thought-out screenplay, influenced by great directors of the past, based on the works of a great author, and benefiting from a masterful leading performance by Ralph Fiennes, who perfected the screenplay’s comedy.

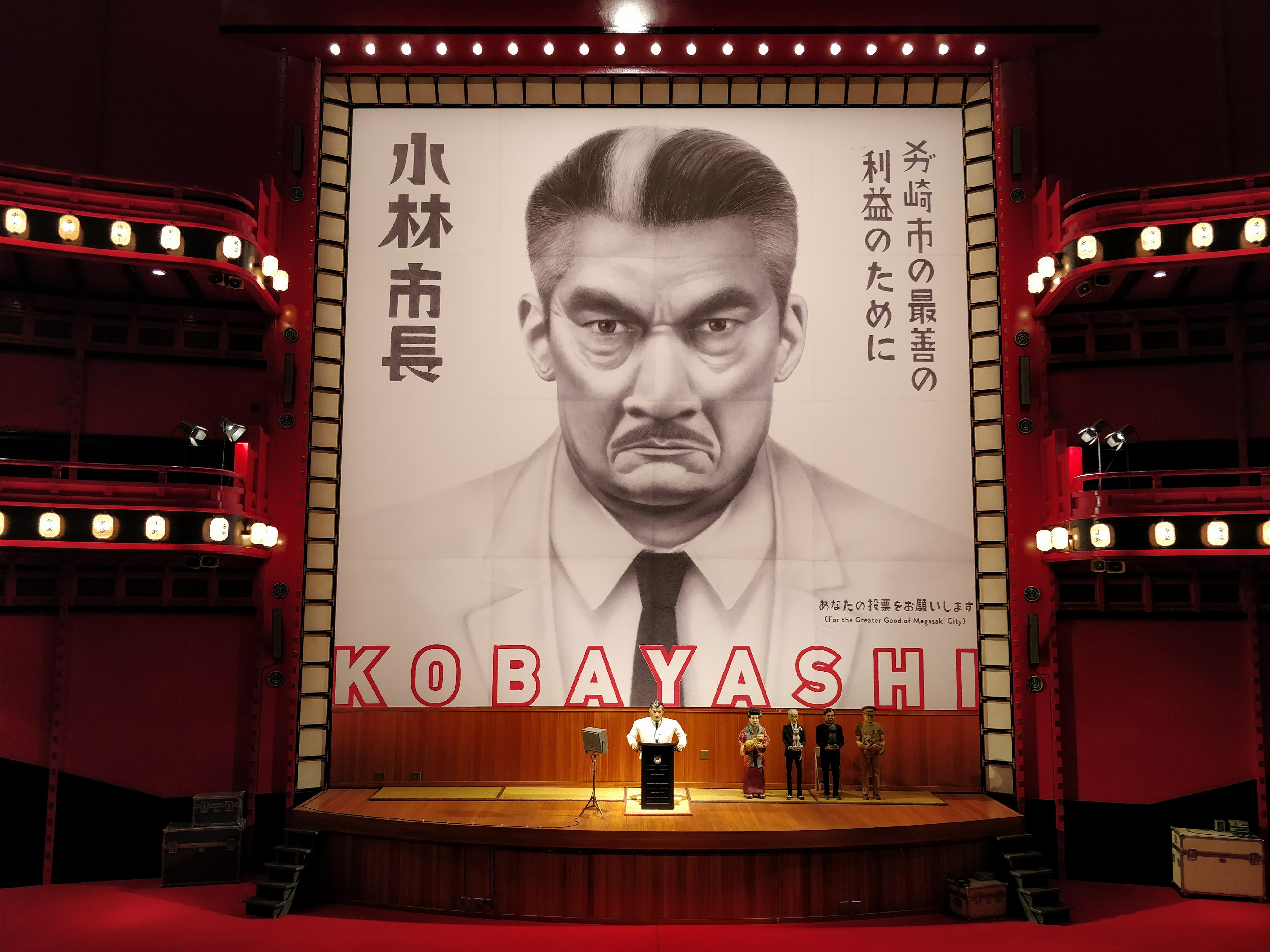

None of this, except for the director’s style, is true of Anderson’ latest feature. Isle of Dogs seems to have all the characteristics of an Anderson film: distinctive and kinetic camera movement sliding perfectly horizontally or vertically; the same cast of actors as always in Anderson’s troupe; a token sixties song to underpin the soundtrack. But style is where it ends. The film is set in a futuristic Japan where a “dog flu” epidemic has led to the permanent quarantine of all dogs, housed on a desolate garbage-dump island (Anderson said that he was inspired by seeing a signpost to the Isle of Dogs in London, imagining what it was like, and then subsequently finding out it was not as magical as it sounded). It follows a twelve-year-old boy, Atari, whose “distant uncle” is the mayor of “Megasaki”, on a quest to find his dog Spots. Atari crash-lands a plane (yes, he just kind of gets hold of an aircraft for himself in an international airport) on the island and meets a pack of dogs played by Anderson veterans Bob Balaban, Jeff Goldblum, Bill Murray and Edward Norton, and headed by newcomer Bryan Cranston. The dogs help Atari to find Spots, while back home in Megasaki an American foreign exchange student Greta Gerwig uncovers a government conspiracy and saves the dogs, Japan and the day. The story itself is reasonably predictable and fairly uninspired. There is a hint of Trump-inspired politics. But is much less convincing than Fantastic Mr. Fox or The Grand Budapest Hotel. The visuals, however, in true Wes Anderson fashion, and perhaps even more so than ever before, are fantastic.

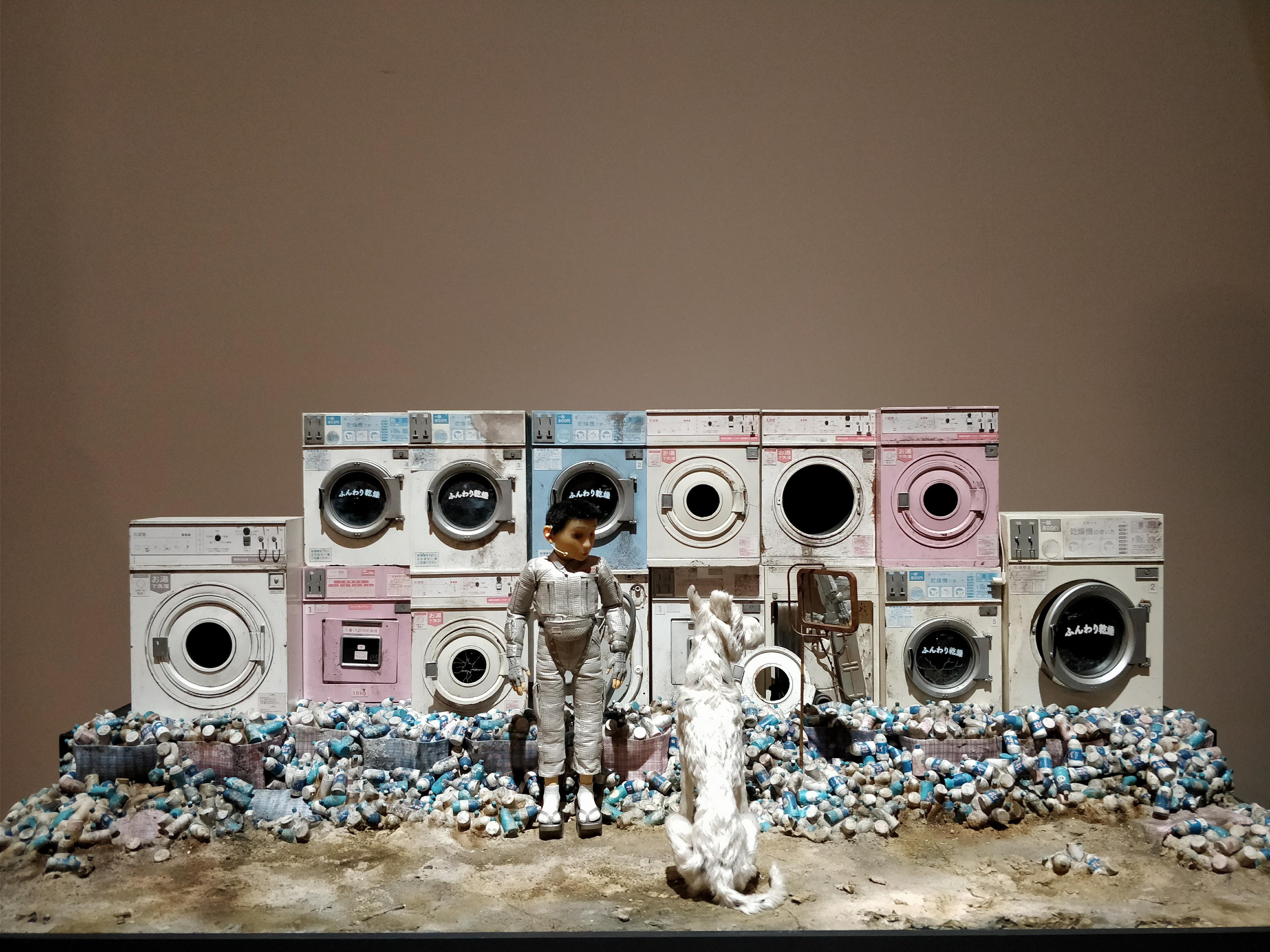

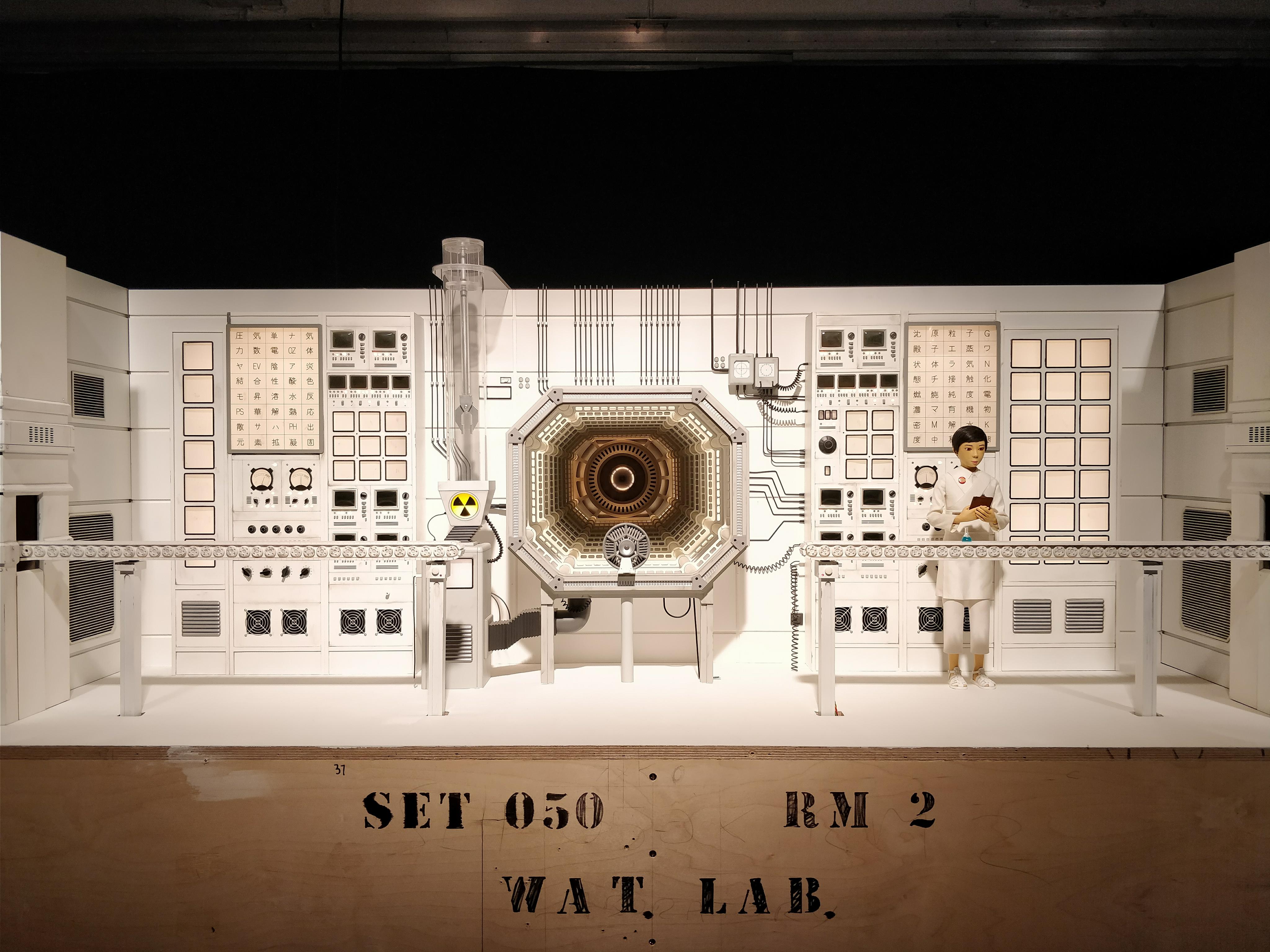

Stop-motion is making a comeback. Laika has been making exceptionally good kids’ films like Coraline (2009) and, more recently, the technically-groundbreaking Kubo and the Two Strings (2016), also set in a fictionalised Japan. Stop-motion is not limited to targeting a young audience, though, as demonstrated by adult films like Charlie Kaufman’s cerebral and haunting Anomalisa (2015). Anderson is no stranger to the medium, having dabbled in stop-motion for fifteen years. In The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2005) he used it for underwater scenes with wacky sea creatures, before making Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) fully in stop-motion. Isle of Dogs one-ups Fantastic Mr. Fox visually, not restricted to the puppet look required to mimic Roald Dahl’s visuals. I had the pleasure of visiting an exhibition of Isle of Dogs’ model sets, and I can say the visuals of the film are a blend of many different things that have already been done, but create something that has never before been seen, in a quite phenomenally beautiful way. Whilst Kubo and the Two Strings had a phantasmagoric realism, Isle of Dogs, like everything Wes Anderson creates, is pure artifice, but in the best way. The characters themselves are not hugely special, but the sets around them are exquisitely beautiful. The low frame-rate increases the artificiality of the film quite purposefully, and in stop-motion Anderson is most at home with his style – kinetic, artificial, and constant physical comedy which morphs camera and characters. In fact, the camera is the funniest character in the film, and its movement makes everything much more funny. The incredible and often hilarious kinetic visuals are supported by an exceptional Alexandre Desplat score (which by far outranks his work on The Shape of Water, 2018) that contains a combination of whistling, hypnotic drum beats also functioning almost as a character in their own right. There is also a central Christmas score, and of course, like every Anderson film, a song by a lightly-troubled sixties boy band.

All this overlooks the big issues of Isle of Dogs: neither the story nor the comedy are quite there. One of the central problems of the film is that however much the stop-motion allows to create unmatched, quirky, and, admittedly often funny visuals, the characters are left very, very far behind. Mark Kermode said in his review of The Grand Budapest Hotel that while Fantastic Mr Fox was “annoyingly smug” and “too smart for its own good”, The Grand Budapest Hotel’s razor sharp comedy “manages to break through that impenetrable, hermetically sealed world”. Here Anderson takes one step forward and two back. Isle of Dogs is even more tediously meta, clever-clever with little in the way of character-driven humour – most of the jokes in the first act consist of sniggering at the fact they are dogs and not people. Each flashback is labelled and numbered. Many of the sneering in-jokes seem like they were written by Abed from Community. The comedy does improve in the second act, and the visuals force you to keep watching in awe. Unlike in his previous films, though, Anderson does not utilise his ultra-talented cast. Edward Norton, who is perhaps the most perfectly suited actor to an Anderson film, is an exception, and Bryan Cranston has a decent run in the main role. The always wonderful Frances McDormand remains wonderful here as a translator. But magnificent actors like Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum, F. Murray Abraham, Tilda Swinton, Ken Watanabe and Scarlett Johannson are completely lost in the background. I don’t know whether the stop-motion is to blame, because their voices are all so distinctive their appearance shouldn’t matter, like it does in The Grand Budapest Hotel. In Fantastic Mr. Fox the stop-motion has no reductive quality to the acting, with even more minor characters like those played by Owen Wilson, Michael Gambon and Willem Dafoe standing out brilliantly. It is the story of most aspects of this film; that the overload of quirkiness muffles everything else to a faint murmur.

Finally, one must question why Anderson decided to even make this film in the first place. It has already been labeled as “tone-deaf”. Sure, it is a celebration of all of Anderson’s artistic values, in many ways a true passion project, and his setting is largely perfect for this. But it seems reasonable to wonder why Anderson would make this film now, when he so obviously ventures into dangerous territory. On one hand it is a celebration and homage to Japanese culture and its great film history. Anderson makes an effort to do justice to the film’s cultural setting, and indeed the film’s protagonist is Japanese, as are many major characters. There is a sweet noble innocence to Atari much like Sam Shakusky in Moonrise Kingdom (2012), or even Zero in The Grand Budapest Hotel, which does come through despite none of his dialogue having subtitles. On the other hand, unlike something like Anderson’s Indian-set The Darjeeling Limited (2007), which respected its setting as a backdrop but not a source of insensitive comedy, Isle of Dogs’ never-ending sniggering leads to problems down the line for Anderson. Jonathan Romney of The Guardian said that “Anderson plays his linguistic hand subtly and wittily, leaving the Japanese dialogue largely untranslated rather than cater too obviously to a western audience”. Anderson’s meta jokes on the nature of translation in film could be hilarious, or, on the contrary, his linguistic hand could be superficially witty, but really plain stupid. Rather than cater more to a Japanese audience (I hardly see why a movie where most of the main characters speak English would be more enticing due to a lack of subtitles), it isolates the Japanese characters from the English-speaking ones. The film is an American film, and a great deal of its audience cannot understand Japanese. To provide the dogs with meaningful dialogue (to an American audience) and deny the Japanese characters to be understood, seems more reductive than progressive. At the screening I attended, I noticed many of the audience around me laughing at parts simply where Japanese characters were speaking their language, untranslated, perhaps because of its complete disparity from the American characters. Maybe that says more about members of that audience than the film itself, but I think – whatever the film’s intention – it risked hitting the wrong note many times. Greta Gerwig as the Pennsylvanian foreign exchange student essentially provided a white saviour role, as she alone uncovers a city-wide conspiracy orchestrated by the mayor. The quirky ridiculousness of it, pervasive of all of his films, for the first time here doesn’t always seem quite right. Where another recent American stop-motion film set in Japan, Kubo and the Two Strings, used its setting carefully, Isle of Dogs smashes together Anderson’s obsessions into something that seems to both celebrate the wonders and richness of a culture, whilst also sneaking in witty jokes at its expense. I’m not the right person to comment on the full extent (or not) of the film’s cultural appropriation, but it did seem that Anderson’s intention is more celebratory than anything malicious; just that his approach to the film’s comedy inevitably causes the film problems.

There is so much fault to find with this film. It has by far the most imperfections of any Anderson picture. Yet I must confess that it is very enjoyable. Anderson has a craftsmanship so unique, so incredibly alluring, that even at his most erroneous it is hard to not be marvelled. The film is exceptional because the auteur pushes his visual style further than ever before, even more impressively in stop-motion. The film’s visuals will be remembered as a true triumph of cinema in any medium, that people will either endlessly rip off, or not dare to mimic at all. The scene where the camera shows us in POV in shadows of people walking into a political assembly, with the camera moving in time with their erratic walking, is one of the most visionary scenes of a film in recent times. Anderson has perfected his style. But almost everything else is second-best, at best. It’s not that it’s bad – it’s enjoyable, superficially clever, often mildly funny – but that’s not enough from one of the most iconic living directors.

6.5/10

Isle of Dogs is released today 30th March across UK cinemas. Trailer below:

Images provided by author following visit to special free exhibition at 180 The Strand. CHECK IT OUT.