Introduction

For most with a more than moderate interest in film, particularly experimentation, surrealism and the avant-garde occupy this discomforting and inaccessible figure. The general genre, style or artistic practice as a whole appears as a murky lake at night with vast jet black obscurity in its depth, directly challenging the human tendency to avoid discomfort. I think it is fair enough for someone to come to the conclusion that the more avant-garde side of any medium’s spectrum might not be their cup of tea; that they see paintings, read books and watch films made for mass-consumption which are easy to follow and preferably entertaining.

Yet art in itself does not ask purely for comfort. Some part of the artistic experience itself is reaching into the depths of the mind or human experience and doing something with it; an indescribable kind of process that occurs beyond just the conscious layers of our existence. If we concede that life is never so simplistic or ‘black-and-white’, then it should naturally follow that the art or “media” it imitates is the same. Trying to reckon with the less conventional, more abstract and at times philosophical aspects of art and film is no easy feat because there is no premade map to navigate this lake. It would be safe to say that diving right in is fine if one is confident enough to attempt the swim. But for others maybe some sort of guidance or crash-course can help. Note that there is not necessarily a super “right” way to “get into” avant-garde cinema, in the same way that there is not really a prescribed way for people to begin watching Western films, Asian independent cinema or blockbusters. There may be recommended structures, anything from trilogies to common movements or vast periods and artistic waves, but the act of watching and engaging with the films themselves serves well as a foundation to it all.

This odd mix of recommendation and “listicle” will be my attempt to try and offer some pointers, interesting spots of discovery and general trends into avant-garde and experimental cinema which seem as diverse as individual human creativities. I have tried to include a few super famous works or what may be considered key works within a possible “history” but try to highlight slightly less well known ones. While the mode itself generally enjoys the slight diminishing of narrative in favour of reflection and the building of a general tone and mood that more so emphasises feeling than interpreting, I would stress that even this article only explores so deep into this lake, and in specific spots. With film’s increasing spread across the world, avant-garde, despite its French etymology, begins to occupy a widely international and human realm. Thus my recommendation, if you remain interested, would be to try and find some more avant-garde, experimental and surrealist cinema on your own, approaching it with some general curiosity but understanding that, like any other film, it may not be perfect.

Beyond Narrative

To say that avant-garde, experimental and surrealist (let’s say unconventional) films have no sense of plot would be an overgeneralisation. In the same way that some people may prefer specific aspects of a place they visit, whether that be the food, the people or the nature among other things, artists and filmmakers of the more unconventional type try to go beyond a prevailing order of narrative and try to stress other aspects that we would also celebrate as part of cinema. This would be out of any possible range of intentions and effects that they may wish to achieve. Part of the fun is understanding how that aspect ties into the work, how the decision to downplay comfortable narrative structure interacts with other elements to try and communicate something. These two films, both incredibly loose adaptations of notable works of Western literature, serve as solid and favourite examples.

Alice (Něco z Alenky) (1988), Dir. Jan Švankmajer

Lewis Carroll’s classic tale of a frenetic, insane journey into the deepest depths of the human psyche and Earth lends itself to an even darker quality here in Jan Švankmajer’s loose adaptation of that same story. The film is largely the same in terms of narrative as the tale is partially localised towards the Czech language and images but develops its additional experimentation via an integration of stop-motion animation. This lends not only an uncanny feeling that twists the reality before the camera and audience but also in even further channeling Carroll’s original thematic ponderings. Where the original Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the many adaptations it has received were centred on being a critical commentary on a thinking and interpretation of reality solely based off of scientific and logical illusion, inspired by Carroll’s background as a mathematician, Švankmajer elevates the understanding of logic’s limits by simply imagining the film as the deeper dream of Alice, narrated by Alice.

In turn the only narrative and logical flow is that which is stripped to the bare minimum. The only intuitive aspect that moves across the runtime here is that of experience, known to be artificial but rendered through the physically real. As a result the stop-motion becomes a precise reflection of a dream, being unreal but still rendered in something understandably linked to reality. One particular benefit of this is that it greatly channels the surrealists’ creative core of engaging with the dreamy subconscious but on an accessible child’s perspective.

This structural metaphor of drifting on the border between these two worlds alone, in my opinion, is worth watching the film for. On the one hand it serves as the basis for an impressive display of visual creativity and material versatility on the part of Švankmajer’s production efforts and the technology available in the 1980s. On the other hand, this also serves an emotional level, where life and therefore death, existence and nonexistence permeates each frame. For in animating that which is inanimate, Švankmajer develops Carroll’s original reflections on the human condition and Alice’s adventurous character as a child by mirroring an imaginary, doll’s-house-like activity and reckoning with this act on a more profoundly existential level.

Funeral Parade of Roses (薔薇の葬列) (1969), Dir. Toshio Matsumoto

Toshio Matsumoto degrades the concept of narrative structure and adaptation further here by taking only a handful of key story beats from Oedipus Rex in order to craft a wider chaotic work of pure energy. It explores, among so much more, queer identity, Japan amid a post-war economic boom, the looming political questions of America and the nuclear age and, most deeply, the human condition amid a society which seeks such an unquestioning degree of conformity. To the extent that a coherent plot thread can be identified, the film covers the life of Eddie, a “gay boy” (Japanese-specific term) who goes about his life reckoning with the shifting Japanese society on the level of the underground Tokyo gay scene. Part of this eventually involves her attempts to usurp the position of “lead girl”. Matsumoto’s experimental editing and visual style makes it clear that the collision of all of these themes cannot be so easily structured in any conventionally linear form of filmmaking. At times documentary, at other times a complete deconstruction if not collapse of the filmic reality, the film is most successful in being able to try and grasp the subject matter of the 1960s underground gay scene in Tokyo. An easy-to-follow linear narrative would have been suggestive of a normative stance towards a prevailing heterosexual, nuclear family and conforming identity that has been socially constructed in a post-war, post-US occupation Japan. One must be critical towards anything conventional and Matsumoto decides that anything goes. To intercut interviews with the actors about their roles in between much of the film’s events, even going as far to have a film critic feature in some form of pseudo-didactic joke, makes the film undeniably unique and most especially absurd.

What I personally love, and what I think should be your highlight, about Funeral Parade of Roses is its cool balancing of thriller and humour, of discomfort and comfort, of partial convention and partial chaos. At times there are genuinely deeply composed shots, static and organised towards the goal of fictional construction rather than documentary realism, usually occupying sombre or dramatic moments. And yet there are static shots but which serve nothing that occupies a sense of normalcy or stability. A bar fight or street brawl shot with next to no consideration for passers-by or a weed and drug-induced claustrophobic rave where the cameraperson is as much of an invisible being as they are a fellow partier. It all lends towards a surrealism of reality-breaking, where memory does not occur in the convenience of chapters and narrative arcs but spontaneous jumpings around of a singular character’s consciousness. Most important of all, it is self-aware to the point of reaching a profound inner peace by even featuring its own troupe of radical, low-budget filmmakers that resemble hippies and Che Guevara.

And even this does not cover all of the film’s diegesis. Matsumoto, and the film, endeavours to examine how this setting and context interacts with the character’s own life, a question not just of nature versus nurture but also reality versus fiction. It is grey and blurry, a black-and-white film that is only labeled so because it is more intuitive than a “grey” film. There is the sense of a mixed quality, forever embedded in some things in life and therefore cinema. When we always live our lives with a mask or persona where inner thoughts rest under, within our heads, is one part necessarily more authentic than the other? Matsumoto only hints towards one solution. Part of the supreme quality of this film is in how it questions the form of the medium to try and reckon with it. Eddie the character and Peter the actor share a lot and yet it is shown clearly that they are separate beings played by the same body, and that is just one part to it all.

Feeling and the Loose Fragments of Humanity

For some other sets of experimental and avant-garde filmmakers, there seems to be a more radical approach taken in trying to practically remove plot, originally written or adapted, entirely and instead focus more on tone, mood and feeling. If one may wish, it is a prioritisation of “affective atmosphere” over any broader technical feat. The vision is one of themes occupying a mental experience which all aspects of production work towards. This is as opposed to themes being broadly constructed through a narrative and creative reality where such themes’ discussion and conclusions are presented more clearly and techniques serve as the creative tools to realise it all. What exactly is this for? Again, the reasons are as numerous as there are creative possibilities. What reveals itself is thus a higher risk of difficulty in engaging in these works as they try to aim straight for looser internal feelings. But do not let this discourage viewing. I would advise just letting it run through and see how the mood steers the viewing experience. While there may be a general feeling that the filmmaker may have intended for thematic reflection, a more personal insight may reveal itself as well. The “vibe” is as much a communication and story as it is a shared tool for meditation.

Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Dir. Godfrey Reggio

Within Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi trilogy Koyaanisqatsi may as well stand as the most ambitiously definitive communication of the vision of a “life out of balance” in cinema, till date. In what seems like part-epiphany and part-manifesto, the film consistently juxtaposes images of grand expanses of nature with a great deal of human technological intervention. We go from mountains to mining and sun rays sifted through clouds to white and red car lights streaming through streets. This is all to consistently build up to Reggio’s main identification that this modern world as he has photographed it has become one of irreversible change, in which life and nature has been replaced. He then examines on a closer level how this circuitry has transformed the circulations and movements of humans, the very actors and collectives who have built these structures and have the ability to collapse them.

These revelations and deep dives are of course best left to a personal realisation in a viewing of the film but the question remains significant in how we can best come to terms with how life, as the title translated from Hopi says, has gone out of balance. On an experimentally cinematic level, Reggio offers but one significantly profound achievement. What I particularly like is that each element, audio and visual, is inextricably linked for a singular sensorial engagement. The score composed by Philip Glass offers a significant backbone to the film by offering a synthesis of the avant-garde creations from other mediums. This primarily transgresses the norms as Glass’s score combines synthesisers and keyboards with the regular thoroughfare of orchestral instruments. By some moments there is an urgency that immerses further into the energy, whatever kind, that serves as a centre of the film, other times the music slows down with the visuals to rest and reflect on where this is all going. Koyaanisqatsi is thus a documentary in the sense that there is no organised sense of stories and events with either cause of effect. It is quite purely reality. But one can either travel forth to these scenes or have these insights of transformation in reality and feelings amplified through the cinematic medium itself.

Papers. (1991), Dir. Yoshinao Satoh

The only short film listed in this article is one that I find particularly compelling as a work of experimental cinema that is intuitive and accessible. Running at a little less than three minutes, Yoshinao Satoh provides an incredibly simple premise of “animating” a massive sequence of newspaper shots and clippings to abstract any sort of meaning. Among the various images that feature, loop once more around the halfway point at a faster speed, are housing floor plans, moves and configurations for Go and Shogi, weather information and repeated instances of words in articles. One of the most notable pleasures that can be found in Satoh’s animation here is in the succession of various human heads from various photographs that combine and flow into a spinning face. The image itself almost deifies the human figures as they appear in the paper even despite the fact that there will be a discernible, individual face if one were to pause the film for a single frame. It is sensible then that the film begins first at a focus of the character “人” (hito, transl. “person” or “human”), as Satoh seeks to try and conjure up some sense of the human spirit and condition through the inhuman object of ink and paper. These “papers” become an interesting symbol, especially significant as it occupies the essence of the animation. For while this ink and paper is intuitively non-human, it is undeniably a human construction.

Everything seen in the film derives from human abstractions of the real world. Go, property floor plans, maps and Shogi are abstractions of territorial control and war. The interpretations go on but what one should at least take away is that this is an incredible expression of the idea that the profound, intellectual and philosophical can emerge from simple objects of everyday life. There is no doubt that we regularly read news articles, check the weather and engage with products of the information age, Satoh’s own animated reflections of this resonate significantly. What I particularly enjoy is Satoh’s use of the experimental classical piece Different Trains by Steve Reich. Where the original vision of the piece was Reich’s own reflections on how trains as this technological innovation are used for a great purpose of improving peoples’ mobility and yet also carried victims of a genocide within the same century. Satoh underlines this essence of modernism and technology to a broader sphere and takes the mechanical tempo of the piece to pace the mechanical world that he sees in the papers. He evolves Reich’s piece to his vision yet also maintains the effort to try and find something still human in the face of all this machinery.

A Partial Reconciliation

This piece will finish with a look at what I consider to be an interesting reconciliation of these two specific approaches to experimental and avant-garde cinema. This type of combined approach is not necessarily consolidated but nonetheless the intersection is intriguing. The first approach tries to have a foundational narrative to it while expanding on other possible parts of filmmaking, whereas the second seems contrary to it by almost sidelining narrative completely for tone. Therefore, a reconciliation would need some essence of a narrative without being too explicit about it to detract from an experiential weight. These qualities do not come as checklists to verify an avant-garde film as reconciliatory between the two approaches. Instead, they should serve as indicators for viewers to intuitively engage with and make use of as a stepping stone into the work.

The Colour of Pomegranates [Sayat-Nova] (1969), Dir. Sergei Parajanov

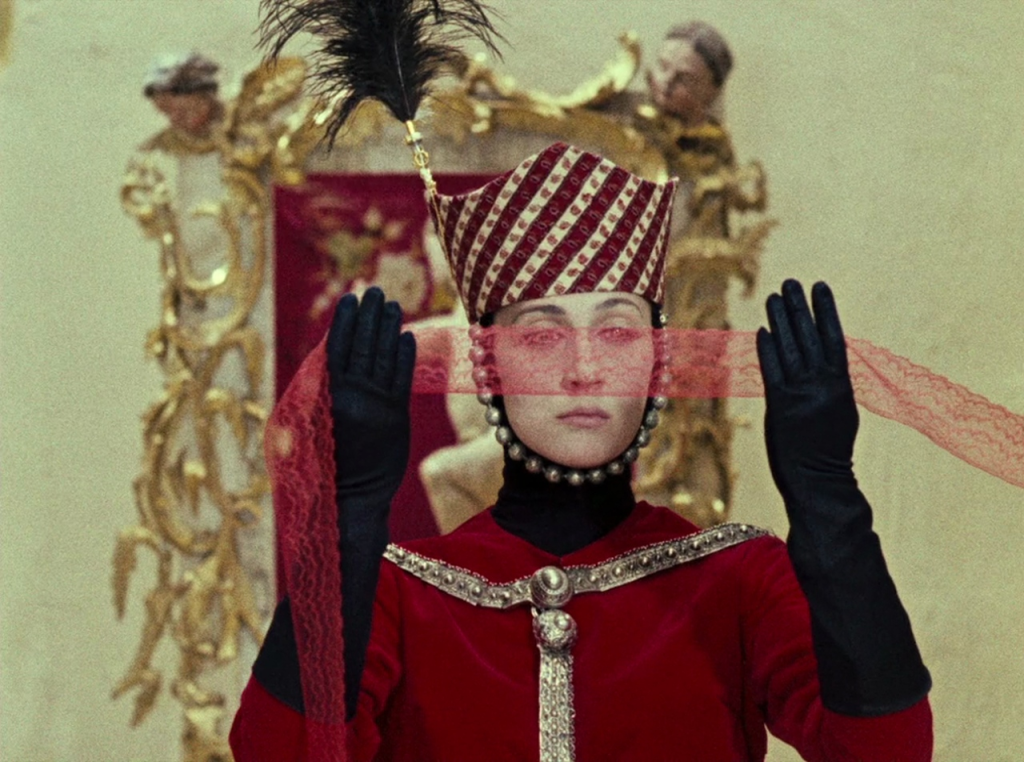

Parajanov photographs what is essentially a series of tableaux-vivants chaptered by the verses that make up the life of Armenian poet Sayat Nova. But this is no ordinary “biopic”. Dialogue is seldom spoken and verses are only occasionally sung. Film as a so-called “audiovisual” medium is made explicit here as each actor and set is let to sit yet still exist in the transient reality of the camera’s frame. There is to some extent a degree of narrative which is to be recognised here, but it is hidden under metaphorical layers of reference, cultural intricacies and visual architecture.

This of course begins to invite the question as to why Parajanov would do such a thing other than to make some very striking colourful shots. Evidently, if one watches the entire film, the core of the film is less so interpretation than meditation. Each image does in fact communicate a poetry made visual, but the power of poetry can also come from the effect of the words rather than any narrative or explanatory meaning implied in their usage. The ebb and flow of life, love and suffering, death and resurrection, is presented here for experiencing, not necessarily reading.

What Parajanov excels in doing meanwhile is providing a living visual testament to Armenian culture and its influences through this film’s engagement with Sayat Nova’s life. Whether that be the tableaux-vivants themselves being an emulation of Persian miniatures and religious art from Eastern Christianity or the props, buildings and costumes which elevate the actors, especially Sofiko Chiaureli who plays around six roles, to larger than life figures, the film is an incredibly rich celebration of life as it appears in the poetry of words and pictures. This persistence of this cultural and human aspect is symbolically portrayed in the real life historical context that surrounds the film. The Armenian identity, already struggling since the early twentieth century, found a defiant voice in Parajanov—whose spirit effectively denied the mandate of “socialist realism” and ultimately led to his incarceration. Such a work speaks so honestly and powerfully towards humanity I feel that it transcended even ideology. It may be specific to these frames and poetic memories, lived only briefly, but I feel they will remain as timeless as they are poetic, aiding those who may be able to meditate on it.

Conclusion

And so that shall mark the end of this brief boating trip into the lake of experimental cinema for now. I hope you, dear reader, may be able to find the time to watch these films and give them your complete attention, hoping to engage in something more subconscious through the screen. Whether that be the narrative drifting of Alice and Funeral Parade of Roses, the sonic and tonal weightiness of Koyaanisqatsi and Papers or the poetic imaginations and dreaminess of The Colour of Pomegranates, the avant-garde will offer many possible experiences so long as one is willing to have them. I feel that in engaging in these works that one may come away with them at least feeling something different, moved or maybe just lightly intrigued but ultimately unperturbed. It is a natural response to feel a bit lost, throw up one’s hands and say “I just don’t get it”. Whether the work comes with this element of fully “understanding” it or not, I hope that someone who has given time and attention to these films will at least feel more encouraged the next time they may face the world of avant-garde film. I shall hope that there is at least less reluctance to immerse oneself in the waters of this approach to filmmaking once more and instead explore more of what cinema has to offer in terms of that internal, meditative change.

Article by Sothysen Tuyhor (zctqtuy@ucl.ac.uk)