London East Asia Film Festival 2023 returns to London with a diverse programme from East and Southeast Asia, including international and UK premieres.

Chris Zhang Goy reviews Green Night, an unlikely romance set in Korea between a Chinese immigrant and a local girl caught up in the dangerous world of drug trafficking.

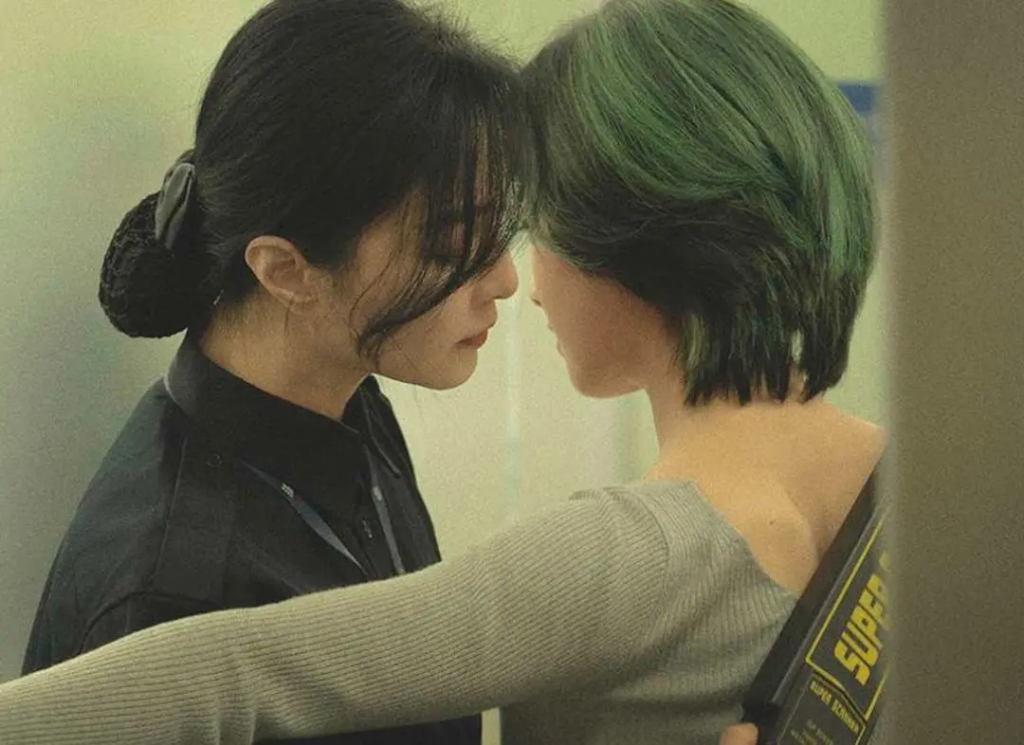

In Han Shuai’s Green Night, Chinese immigrant Jin Xia (Fan Bingbing), who works in customs at Korea’s Incheon Airport, unexpectedly encounters a local green-haired girl (Lee Joo-young) who is entangled in the world of drug trafficking. They form a unique bond not only based on their reliance on exploitative men, but also the challenge of navigating language barriers. Together, they embark on a treacherous adventure that initially appears to be a classic same-sex romance thriller in the vein of Plata Quemada. However, as the film’s conclusion approaches, the seemingly pivotal, green-haired girl, vanishes like a pebble cast into water, leaving only ripples in her wake. This twist undermines any attempt to compare this film with Blue Is the Warmest Colour as a profound misreading.

Green Night isn’t a typical same-sex romance film. While it delves into romantic themes, incorporating sexuality and violence, it’s more than just a love story. The film caused a stir on Chinese social media, not only as it marks Chinese-mainland star Fan Bing’s cinematic comeback following a tax-evasion scandal, but due to its portrayal of Lesbian Love. This became a hot topic even before its premiere at Berlinale, upstaging public attention on another young actress Lee Joo-young, who previously worked with acclaimed director Hirokazu Kore-eda, and director Han Shuai. These explicit scenes of violence and sexuality make the film a no-go for mainland Chinese screens. Unsurprisingly, some have extended the film’s message of resistance beyond its storyline to comment on these real-life issues of gender oppression and stringent censorship. However, it’s clear that Han’s intent is to explore and convey a universal yet profoundly personal experience. The core theme here is “forgiveness”, and the entire film can be viewed as a wild dream journey toward Jin’s self-redemption. Her chance encounter with the nameless green-haired girl starts off surreal but ultimately becomes transformative for both women. As the narrative unfolds we learn about the corrupt power structures surrounding our male-dominated pair through the sharp contrast between the orderly customs world and the shadowy drug trafficking underworld. Realising that her boss is involved in drug trafficking, and in need of money for a visa, Jin agrees to help the girl avoid the police. A rough body search by the drug traffickers serves as a stark reminder of the frailty of Jin’s position, as she leans on her local husband to maintain power. The stilted yet resilient communication between these two women, as they navigate a web of Korean and Chinese, adds to the tightness of their secret alliance.

Their intertwined destinies unfold through their shared childhood wounds, and a deep-seated guilt that weaves through the tapestry of their lives. Jin had reported her mother to the authorities, leading to her mother’s exile, while the green-haired girl narrowly escaped a terrible car accident due to missing her school bus. Their quest for liberation from the shackles of guilt takes centre stage and pushes the characters forward. It makes sense that the keyword that triggers their vengeful fury becomes, “I forgive you.” Having narrowly escaped a police investigation Jin almost commits suicide due to feelings of guilt for betraying her mother, but a small bottle of green hair-dye lights her desire to survive. She dyes her hair green and embarks on a journey of self-redemption through murderous vengeance. However, in the end, it is by finding self-forgiveness over the forgiveness of others that Jin actually grants herself redemption.

The guilt that binds the green-haired girl to Jin’s mother forms an essential cornerstone of the story, but the film frequently gets lost in the spectacle of violence which turns an enigmatic and dreamlike adventure into a more straightforward tale of revenge. During a post-screening interview Han even expressed regret for not exploring the intricacies and parallels of the relationship between the green-haired girl and her mother further.

The film’s cinematography is brilliantly orchestrated by Hyeon-seok Kim and Matthias Delvaux, and enhanced by the haunting musical score of Hank Lee. The intro sequence exudes an almost futuristic noir vibe which sadly doesn’t persist throughout the film, but the choice of a red and green colour palette provides an emotional signpost to mark the transition between tense and relaxing scenes. The film subtly alludes to contemporary Christian influences in South Korean society and hints at their role in shaping characters like Jin’s husband-in-law Lee (Kim Young-ho), a devout yet depressed oppressor. The film aims to subvert society’s expectations of women as the “perfect victims”, as most notably seen when our two protagonists take advantage of a cross-dressing homosexual by infiltrating his hotel-room, which offers a new dimension of “liberation from guilt”. Yet, the lack of focus in the visual narrative ultimately leaves us pondering how the film’s intentions differ from the battle cry of “all males go to hell” in radical feminism.

In the midst of an escalating gender struggle, which demands women to manifest “power”, “fighting spirit” and even “aggressiveness”, I do appreciate that Han continues to explore the subtle facets of the female psyche, much like in her previous work in Summer Blur. Han aims to preserve the intricacies of reality and attempts to blend it with allegorical storytelling. However, here it unfortunately results in a lot of ambiguity. The ultimate outcome is that, while the director admirably endeavours to internalise its conflicts within its characters’ personal experiences, rather than resorting to cathartic outbursts of retribution, audiences of neither gender are likely to find themselves fully convinced. At the end, Jin embarks on a high-speed ride across Incheon Bridge. No audience can be sure that her joy comes not from the thrill of revenge but from the fact that, even if she becomes the perpetrator of violence, she no longer needs the forgiveness of others. This uncertainty shows the director has failed to effectively communicate their intentions.