BFI’s London Film Festival is in town! The FilmSoc Blog is back for the 64th edition of one of Europe’s largest film festivals, delivering a first look at the hits and misses of the 2020-21 season.

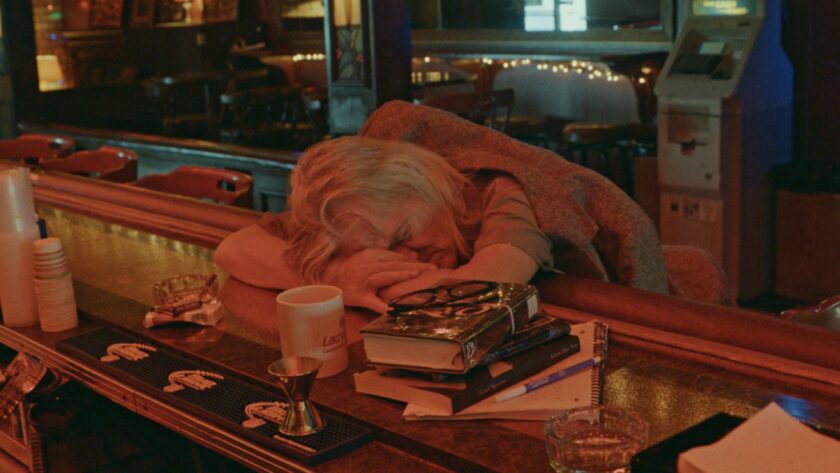

Milo Garner muses upon an inebriated quasi-documentary set in a Las Vegas dive bar.

Like many in the midst of lockdown, I have been thinking often of alcohol and of opium. In drifting toward and then thoroughly into the intellectual hinterlands of such subject matter I came upon the hefty, megalithic writings of one Robert Brimson. His commonplace opus – On Narcotic Abuse and the Kernel of Knowing – is perhaps better regarded among literary circles than pharmacologists. The closing chapters are especially vaunted, written entirely in the daze of his subject opiates. But my concern came chiefly in the introductory paragraphs, with his description of opium dens a particular diversion: “… and in entering the afore-defined ‘opium den’, one is confronted not with a congregation, nor with any kind of communal feeling. Instead, one encounters yet more ‘dens’ – each participant enshrined and untethered, alone in his company. These establishments persist in their common form for reasons of commerce and convenience. One should not mistake their popularity with social connotation.” A later excerpt is salutary, and concomitant: “In seeking a modern or American equivalent, many are quick to approximate commonality in the so-called American ‘dive’, or ‘drinking den’. No doubt they are seduced by the salacious offerings of Wilde, who speaks of opium dens as places where ‘one could buy oblivion’, or as ‘dens of horror’. These ideas are miswrought. … The American dive is not a personal sequester, nor somewhere familiar with the anointed silence that hovers among drinkers of poppy tea. The American dive invites the expurgation of the soul: it is there that men, and sometimes women, find it necessary to speak gaily, or drearily, of their supposedly true conditions. Alcohol – the primary intoxicant of these establishments – encourages outward expression and intercommunicative tendency. Furthermore, alcohol abets anxiety, despair, desire, confidence. … The American dive is as materially different from the opiate-establishments in Europe and Asia as is conceivably demonstrable, beyond each providing the service of intoxication en masse.”

Brimson’s musings and misgivings on the archetypal dive bar are salient when mustered against the Ross brothers’ Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, a documentary (of sorts) that captures a Vegas dive bar on its last day before closure. It is an accidental harmony: shot in 2016 and premiering on the precipice of pandemic, the Rosses have constructed a film that serves as a monument, or mausoleum, to the bars and pubs facing their final days in the shadow of pandemonium. Over eighteen hours of shooting – from first to last call – The Roaring 20’s serves stage to the familiar extremities of a soused clientele. Resembling Brimson’s description closely, we bear witness to declarations of undying love, or men in search of a battering, or sudden, earnest, absurd assertions of closely-held absolutes. There is temptation to see this bar as humanity simplified: nuance removed or reneged, an awkward, bumbling expression of the total truth, all of the time. Radical honesty in practice. That old Latin saying, a complaint about something in the wine. But there is more to the honest drunk than honesty. In drunkenness there is admission, as could be well-attested, but there is also projection. People often do not say what is true but what they think ought to be true. The difference is subtle and enormous. This is why lovers of the night are often not lovers of the morning, or why the wise men giving sage advice cease abruptly with the rising of the sun. All of which is apparent in watching: these men and women may drift closer to their unabridged selves, but also closer to general types, closer to unmoulded substance. I do not think we are shown their actuality; only a shade. A loud, brash, slurring shade.

Though so far as the truth is concerned – and it is concerned a great deal – the distance between apparent truth (the theatre of drunken revelry) and actual truth (those statements made that are surely incontrovertible) becomes something of a running joke. Most obvious in the bar’s television, which plays nothing but classic movies through the night. The first film visible is The Cranes are Flying – the greatest and most moving film ever made. The scene witnessed is the moment Boris is shot by his Nazi pursuers. He looks up suddenly, he and the camera witnessing the infinite welter. The camera begins to spin. What will follow, unseen in this snippet, is a vision of Boris’ unlived life. The woman he loved. The marriage he did not have. A memory of running up a tenement staircase. It is all supremely upsetting. But in that shot of sky and forest, some profundity has already been communicated. All this in spite of (and due to) Kalatozov’s proclivity for the wantonly expressive and artificial means of cinema. Here is truth despite the equipment of fiction. The Rosses stitch their film completely from this material, summative moments of realisation. The effect is often comedy, but if one could impute any failing on Kalatozov (or the Russian masters in total), it is their distinct absence of humour. The brothers Ross observe their situation comedically because to do so in any other way would close on unbearable. The depression of this squalid bar is not hidden, nor is it difficult to find. But those other feelings invited therein, implied by its presence, are made as equals. While the bar represents the utmost failure of its patronage, it just as much resembles a final stopgap. Like one of those grisly suicide nets installed in a Chinese manufactory – a disconcerting presence, but perhaps better there than not. Where will these layabouts drift without their regular haunt? And when all the regular haunts are shuttered up and gone away? There seems some cause to celebrate the beast before it expires.

Only many of these men and women are not, as might appear, the guileless regulars this bar doubtless attracts. An unstated proportion are actors, auditioned intensively for their roles. The exact degree to which the events of the film are ‘contrived’ is not entirely clear. As much as the Rosses go unmentioned in the diegesis (despite hulking their cameras around the bar all night), their directorial, editorial presence is palpable. It seems that while the general arc of the night is defined – significant events, certain beats – the detail and prosecution are not. Actors though they might be, these actors are drunk. So whatever acting they might be doing must be countenanced with the reality of their intoxication – and whatever any actor is doing must be countenanced with whatever the genuine inhabitants of the bar are doing by their side. The bar itself engenders the fiction: we are told it belongs to Las Vegas, Nevada. It is in fact situated in New Orleans. And it’s still open, four years on. The overwhelming sense gained in watching Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets is how little the discrete truth matters. The Ross brothers make it their cinematic dictum to bend signifiers of truth around one another: classic cinema nested within documentary form; actors mingling with regulars, each mingling with alcohol; and then a dislocated premise, designed rather than discovered. The effect remains unchanged; the Rosses do not blend what is and what isn’t as an act of disillusionment, but the very opposite. This is a welding of the forms, an embodiment of Brimson’s archetypal dive bar through fiction and through fact. Cinema, in essence.