Earlier this year, I caught a re-release of Luchino Visconti’s family saga, Rocco and His Brothers (1960) at BFI Southbank. While I thoroughly enjoyed the film, the viewing experience was a different story. It was during the devastating climax of the film, when Alain Delon’s Rocco, in a fit of desperation and brotherly virtue, crashes through a window to stop his younger sibling from reporting the eldest brother’s murder, that I started to get annoyed by the incessantly dismissive laughter from two men seated behind me. This act, however morally ambiguous, is a pure and symbolic shattering in the name of familial bonds. Their chuckles were not a one-off but a constant refrain throughout the film.

I initially dismissed this as an isolated incident, but a pattern emerged in conversations with friends and in online forums. My father recalled that a woman beside him dismissing Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955) as “silly”, whilst many reviewers noted how screenings of John Woo’s heroic bloodshed epic, The Killer (1989), were punctuated by ironic laughter during its tragic and brutal final minutes. These are not just outliers; it is a cultural trend. Nowadays, we are becoming unequipped to handle the raw, extreme language of melodrama – a loss as tragic as the melodramas themselves.

Prominent French New Wave filmmaker Robert Bresson famously claimed that “drama will be born of a certain march of non-dramatic elements.” By extension, everything can be dramatic. Melodrama takes this a step further – it is the art of externalising the internal passions normally repressed by the workings of society. This is why it is often centered around questions of gender and identity, topics frequently dismissed when labeled, in a derogatory tone, “women’s weepies”. Melodrama operates on a symbolic frequency, using a heightened visual and emotional grammar to articulate feelings and societal critiques too powerful for subtlety. Its language needs to be expressive to reach those privileged enough to ignore the grandiose issues it depicts. Consider two pillars of this form: the Technicolour melodramas of 1950s Hollywood and the 1980s Hong Kong action melodramas.

The most prominent figure (or perhaps the pioneer) of the former is none other than Douglas Sirk. In his 1955 film All That Heaven Allows, the cold blue light of Cary’s mansion is not merely a mood but the visual embodiment of her emotional isolation. Contrasted with Ron’s warm and earthy cabin, it stages a direct dialectic of social class, visualising the societal pressure that threatens their “scandalous” relationship. But the standout moment is when Cary comforts her bullied daughter, Kay, and a window produces a rainbow prism across the room, bathing them in a spectrum of different colours. This is emotion painted in bold, symbolic strokes, externalising the prism of judgement and dilemma these two complex women are forced to navigate.

Gloria Talbott and Jane Wyman in All That Heaven Allows (1955)

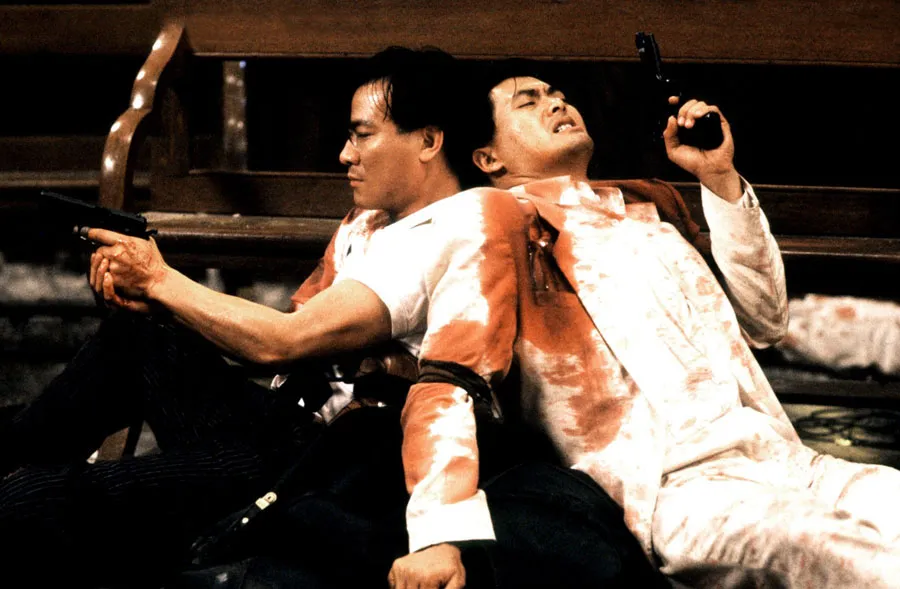

However, this form does not stop at the domestic sphere, as Hong Kong action filmmakers like John Woo transposed this expressive grammar into the criminal underworld. In his 1989 masterpiece The Killer, the slow-motion doves and endless ammunition are not just stylistic flair; they are the equivalent of a soaring opera duet, that of the musical call and response. A blood-soaked embrace is a tragic lover’s farewell. The gunplay is not commenting on violence, but on the externalisation of inner conflict and chivalric loyalty, a ballistic opera of brotherhood shared between Chow Yun-Fat and Danny Lee (a dynamic echoing Woo’s earlier film A Better Tomorrow, with Ti Lung filling in for Lee). Hence, the goal of the melodramatic language is catharsis – a direct, visceral, and shared purging of emotions. It reflects how feelings are on the inside: overwhelming, operatic, and larger than life.

Danny Lee and Chow Yun-Fat in The Killer (1989)

To understand why this cinematic language causes laughter, we must turn to the contemporary default of cinema – realism and naturalism. Films like Past Lives (2023), Aftersun (2022), or the works of Wong Kar-Wai are celebrated for their “organic” and “authentic” progression of feeling. Their language is one of subtext, suppression and subtlety. In this form, emotion is a silent, private language, whether through a hesitant glance that lasts a second too long, a half-finished sentence, or a lingering moment of silence. The filmmaking style is often invisible, prioritising a sense of unfiltered and unmediated intimacy that asks the viewer to look for nuance.

Widely considered Wong’s magnum opus, In the Mood for Love (2000) is a masterclass in this form. When the protagonists, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan, discover their spouses’ mutual affair, their performance (for their neighbours and for each other) begins as their gestures are meticulously controlled, and gazes become apathetic yet constantly attentive. In the film’s first taxi scene, when Mr. Chow reaches for Mrs. Chan’s hand, her reluctant withdrawal is not a rejection but a heartbreaking display of containment. The dilemma is not externalised through a sob or an incident; instead, it is internalised, manifesting in the unbearable distance between them and the weight of their ‘affair’ left unsaid. The audience is thereby rewarded not with catharsis, but with the melancholic satisfaction of understanding. It is a cinema of contemplative observation, aligning with the modern style, which values emotional subtlety and the prospect of being a voyeuristic observer rather than a vulnerable participant.

In the Mood for Love (2000)

The modern audience, now fluent in the language of realism, has become emotionally illiterate in the dialect of melodrama. This clash of the two cinematic ideals explains the dismissive, self-important laughter that is present in screenings of such films. This is further enabled by cynical rationality of modern times. In forums like Instagram, where sincerity and authenticity are seen as staged performances, irony becomes the only course of engagement. This trend encourages more people to be hyper-critical – to question everything put in front of us, valuing rationality and facts above all else, especially above what we collectively dismiss as “unrealistic” emotion. Thus, when confronted with something like Alain Delon crashing through a window, the modern viewer does not see an act of desperate familial duty. Instead, they see a logical flaw: “why did he not just use the door instead?” They process the image literally, missing its melodramatic symbol. Confronted with the raw, unironic emotion of melodrama, the modern viewer’s only instinctive, self-defensive response is to laugh. It is the sound of an audience that protects itself against sincerity.

The dismissal is a profound loss of a cinematic language. Melodrama is never just mindless excess; it is an unrestricted approach to the most impassioned emotions that we are never allowed to show. Such passion nowadays is often dismissed as inauthentic. But, there is nothing insincere about being moved by melodramas: to choose emotional truth is to be human. The laughter that punctuated the screening of Rocco was not a judgement on the film’s quality, but a symptom of the wider culture that has become detached from sincerity. I am not here to criticise the modern cinema of realism, but I invite you to be more open to melodramas. It is to accept that there is more than one way to express emotion and passion on screen, and hopefully this touches on a part of ourselves that is unafraid to feel our emotions.