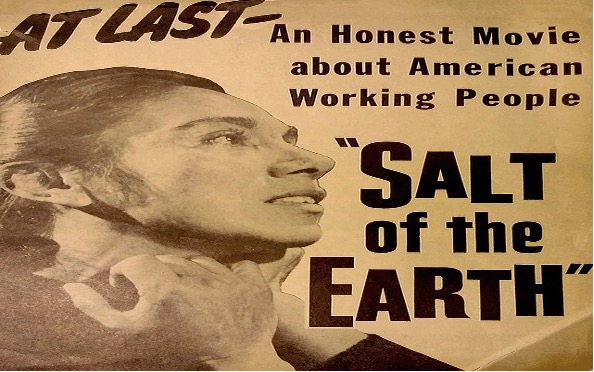

Edward Lahner looks back on Herbert J Biberman’s Salt of the Earth, telling the remarkable tale of its production and reception history from the McCarthy Era to the modern day.

On March 10, 2024 at the 96th Academy Awards, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) was duly rewarded for its critical and commercial success, walking away with a remarkable seven Oscars, including the prestigious best picture and best director awards. Nolan’s seminal biopic not only stood out because of a consensus that protagonist J. Robert Oppenheimer was the father of the atomic bomb but also due to its intense focus on the anti-communist witch-hunts that later tarnished the image of a national hero. 21st Century audiences previously unfamiliar with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare watched on in horror as a man who played a crucial role in ending World War Two was psychologically ripped to his core for communist affiliations predating his direction of the Manhattan Project. However, 70 years before Oppenheimer and in close proximity to the Los Alamos Laboratory where the physicist worked, the production of another film was directly opposing the anti-communist sentiment sweeping the nation at the time. Produced as the Red Scare gripped the U.S., Herbert J. Biberman’s Salt of the Earth (1954) proffered a cinematic resistance to the stifling socio-political environment that adversely impacted marginalized communities throughout the country. Centered around the experiences of picketing Mexican American workers, Biberman’s film challenges the racial, gender, and labor divisions that upheld a repressive postwar order. Based on the 1950 Empire Zinc Corporation miners’ strike in Hanover, New Mexico, the film acts as a cultural microcosm of the broader obstacles faced by marginalized communities during this epoch, and how they united to confront them. The makers of Salt of the Earth countered obstacles on two levels: it was not only the film’s social commentary that challenged the status quo, but also the threat to its very existence as a production as Biberman’s crew faced a barrage of barriers from Red Scare forces determined to eliminate his counter-narrative.

Salt of the Earth’s importance is made visible via its historical context, because it is really the background of Biberman’s radical retaliation against the Red Scare which explains why he chose to direct the film. Biberman was a member of ‘The Hollywood Ten’, a group of left-wing filmmakers who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). During his own 1947 HUAC appearance, Biberman used his spotlight to condemn the process, deploring the committee’s invasion of “the right, not only of me, but of the producers to their thoughts, to their opinions.” After refusing to explicitly deny his communist affiliations, the director served a six-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress, and was subsequently blacklisted by the Hollywood studios and unions altogether. 1947 can be pinpointed as the year that the paths of Biberman and New Mexico’s Local 890 of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers first crossed. At the same time Biberman was facing the wrath of HUAC, the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act was passed, requiring unions to certify that their elected officials were not Communist Party members in order to be recognized by the National Labor Relations Board. For the exact same reason then, Biberman was punished for refusing to deny his communist ideology and the ‘Mine-Mill’ union was kicked out of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Both alienated for their political views, the blacklisted filmmaker and the expelled union shared a status as Cold War outcasts who were forced to operate independently from the organizations that were supposed to protect them. The Local 890’s strike against Empire Zinc Corporation had caught the attention of Biberman and his fellow blacklisted creatives in 1951 when a ladies’ auxiliary took over after a court injunction had prevented their male counterparts from picketing. The result was new contracts in January 1952 which led to better pay and living conditions for the miners and their families. Moved by how the community had overcome socially entrenched gender divisions, blacklisted producer Paul Jarrico encouraged Biberman to direct a feature film on the strike revolving around an inter-marriage conflict.Involving the mining community was pivotal in Biberman’s fashioning of a radical, pro-union project that directly countered the obstacles faced by Mexican Americans and blacklisted filmmakers during The Red Scare. Jarrico later proudly declared that Salt of the Earth was the first U.S. feature film “of labor, by labor, and for labor.”

After visiting the mining community involved in the strike, writer Michael Wilson did not simply write a script solely in the filmmakers’ terms but sent a draft to the Bayard union. This ensured that the predominantly Mexican American mining community possessed agency over how the film presented them, permitting the removal of any scenes that potentially inflamed negative stereotypes of Latinos in the U.S. Once Local 890 members had unanimously consented to a feature film being made about them, Wilson set up a union committee (including members of the ladies’ auxiliary) who were able to make alterations before shooting. The result was a considerate creative process where the miners and filmmakers worked together in tandem with the film’s aim of bridging differences. The casting of Clinton Jencks, a white union organizer, as Frank Barnes illustrates Biberman’s sensibility in this ambition. Jencks was a widely respected union representative for the Local 890 of ‘Mine-Mill’ who helped to mobilize Mexican American miners to call for better conditions. During a poker game scene, Barnes and the male protagonist Ramón Quintero are able to openly discuss the prejudices that divide Anglo and Mexican American workers. Ramón is criticized for “lumping [Anglo bosses and workers] all together” and admits his ingrained suspicion over Barnes’ racial identity. Ramón praises him for being “most of the time… dead right” over strike strategy, but asks Barnes if he is “afraid [Mexicans] are too lazy to take initiative” because of how comprehensively he organizes the union by himself. Barnes rejects this assertion, but confesses that he’s still “got a lot to learn” after failing to recognize a portrait of modern Mexico’s founding father, Benito Juárez. By deploying two non-professional actors from the same union in this scene, Biberman avoids creating a contrived bond between the Anglo and the Mexican, creating a space for open discourse where two activists powerfully agree to look beyond their differences, and unite against an oppressive corporation firmly attached to the repressive status quo. The casting of the President of Local 890, Juan Chacón, as Ramón Quintero is similarly inspired, furthering the verisimilitude of Salt of the Earth. Following instructions to speak the lines to himself to learn how to act, Chacón’s gripping performance won over Biberman who was initially hesitant to cast him.

What about the roles of women in the strikes and Salt of the Earth? In truth, if the film says anything, it is that women are crucial to popular movements that seek to overturn a repressive society. The Taft-Hartley labor injunction that prevented the miners from striking only functioned on the presumption that women in the community were too preoccupied with domestic responsibilities to participate in industrial action. Consequently, the fact a women’s auxiliary united to prolong the strike caught Empire Zinc Corporation completely off guard as well as catching the attention of the blacklisted filmmakers. Biberman, Wilson, and Jarrico were drawn to the notion that women had risen above their traditional gender roles to support their husbands and how this had eventually ameliorated not only the miners’ working conditions, but also their living arrangements. Rosaura Revueltas stars in the leading role of activist and housewife Esperanza as she fights for a more prosperous future. Her name translates quite literally to ‘hope’. It is through her personal anguish, not only as a mother carrying an unwanted child in adverse living conditions, but also as a wife in a marriage devoid of fulfilment that we truly see the mobilization of women in the film. For much of the film, Ramón resents his wife’s newfound purpose as a union activist,sitting defeated on the sidelines and bemoaning the subversion of gender roles that make him the unpaid household worker. The night Esperanza returns from jail, she confronts her husband’s attitude, condemning his decision to go hunting and abandon the strike: “The Anglo bosses look down on you, and you hate them for it. Stay in your place, you dirty Mexican – that’s what they tell you. But why must you say to me, ‘Stay in your place’? Do you feel better having someone lower than you?” Ramón raises his arm to hit Esperanza, but hesitates and is shamed by his wife for resorting to the dominant physical advantage of his damaged masculinity. Having left for the hunt the next day, Ramón develops his gender consciousness and rushes back to support the strike, inadvertently helping to prevent the picketing women from being evicted. Although this utopian resolution may seem slightly contrived, it permits Biberman to hammer home that marginalized groups have historically been pitted against each other, and that by uniting and overcoming differences such as gender, they can successfully counter the status quo that divides them.

Frenzied by anti-communist hysteria, Red Scare provocateurs not only blacklisted dissidents within the Hollywood mainstream, but also went out of their way to encroach upon filmmakers working outside of that system. Biberman, Wilson, and Jarrico had to withstand direct ideological as well as physical Red Scare attacks on the production and distribution of their counter-narrative, Salt of the Earth. After it was discovered that Biberman was directing a film in New Mexico that countered the postwar order, U.S. Representative and HUAC member, Donald L. Jackson delivered a speech in Congress on February 24, 1953 where he declared: “This picture is deliberately designed to inflame racial hatreds and to depict the United States of America as the enemy of all colored people.” This direct Red Scare attack by Jackson actually originated from The Screen Actors Guild leaking the shoot to labor columnist, Victor Riesel. Riesel in turn suggested that the production’s close proximity to the Los Alamos Laboratory, where Oppenheimer directed the development of the atomic bombs, was no coincidence and posed a potential threat to U.S. national security. Consequently, Biberman’s film was exposed to attacks during production, first of all from immigration officials who deported Rosaura Revueltas just days before shooting ended due to a passport error which the government would later admit was their fault. The most violent insurgency however, came from an anti-Mine-Mill vigilante committee who fired shots at Clinton Jencks’ parked car and assaulted crew members at the Bayard union hall. Despite this, Biberman was able to finish shooting the film, adapting to the loss of his lead actress by filming her last scene as well as her voice-over narration near Mexico City. Biberman had to overcome the further hurdles of editing and distributing the film after Howard Hughes, who had considerable influence in the Screen Actors Guild, plotted to prevent the film’s release. Hughes wrote a letter on March 18, 1953 to Congressman Jackson, asserting that “Biberman, Jarrico, and their associates cannot succeed in their scheme alone.” So, the filmmakers had to take extraordinary measures to complete Salt of the Earth within this hostile milieu. In the silence of the night, editing took place across Southern California whilst technical work was completed in a Chicago laboratory. Finally, in terms of distribution, the industry-wide boycott of Biberman’s Independent Production Corporation (IPC) severely constrained the film’s first run in 1954, flooding the film with negative reviews; Biberman retaliated by previewing the film in New York for labor groups and progressives while negotiating with theatres. In the multiple strategies through which the postwar order sought to destroy Biberman’s Salt of the Earth we see the staggering degree of cultural censorship which defined the epoch.

In their book, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky introduced a propaganda model of communication to theorize how U.S. mass media had covertly manufactured the consent of the governed over the course of the 20th century, thus explaining the rapid spread of moral panic provoked by the Red Scare. Their central argument was that U.S. mass media “are effective and powerful ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function, by reliance on market forces, internalized assumptions, and self-censorship, and without overt coercion.” In an interview about his subsequent 1992 documentary Manufacturing Consent, Chomsky explicitly praised Salt of the Earth for its visualization of the waves of popular movements where the tide is pushed by ordinary, unknown people. He compared Biberman’s work with a far more successful film from the same year by another director with a communist past; Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954). Unlike Biberman, Kazan provided names in his 1952 HUAC testimony, damaging the careers of actors like Art Smith in order to save his own. Chomsky notes that On the Waterfront was lauded by the establishment precisely for its anti-union stance, highlighting how a crooked union boss betrays the working man.Whereas, Salt of the Earth, an optimistic pro-union film with a utopian view on overcoming adversity, was the nemesis of the status quo. But the tides have turned. Herbert J. Biberman’s Salt of the Earth was selected to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry of significant films in 1992, as its opponents appeared to concede its cultural and political importance as a film unbound from the repressive McCarthy years during which it was made. In defiance of the storm of Cold War obstacles to its counter-narrative as well as its production, Salt of the Earth sailed against the wave of the Red Scare, a wave that was to be crested by Oppenheimer seven decades later. Whilst Nolan’s work received adulation for its excellent, but retrospective critique of Cold War militarism, Biberman’s film deserves more praise for its immortalization of a small Mexican American mining community who, in the face of direct Red Scare oppression, successfully harnessed the power of unity.