Caleb Tan reviews Thai comedy drama How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies, a tear-jerking box-office sensation that has warmed the cockles of many hearts across Southeast Asia.

How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies (2024), Thailand’s entry for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, marks a historic milestone as the first Thai film to make the Oscar 15-film shortlist. A heartfelt drama with a dose of humour, Pat Boonnitipat directs the tale of a young man who decides to take care of his ageing grandmother, less out of love than with his eyes set upon her million-dollar inheritance. Inspired by the domestic truths of every family, the film sparked a viral social media trend of tearful post-screening reaction videos.

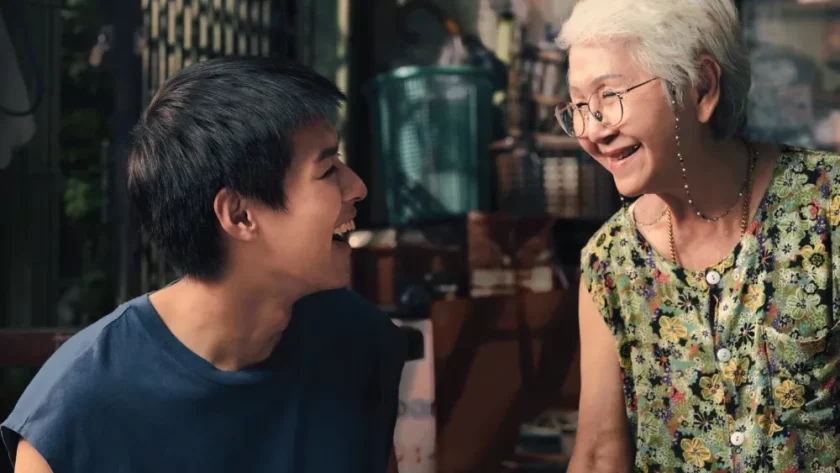

The film stars Thai actor-singer Putthipong Assaratanakul, better known as “Billkin”, and Usha Seamkhum, in their feature film debuts, as grandson and grandma, respectively. M (Putthipong) is a college dropout who used to perform well in school, but is now scraping by as a video game streamer. M rarely visits or spends time with his grandmother, Menju (Usha), affectionately known as “Ahma”. However, upon learning that Ahma is diagnosed with late-stage stomach cancer, he devises a plan to become her full-time caretaker, hoping to secure her fortune. He meets his cousin, Mui, who received most of their late paternal grandfather’s estate after being his full-time caregiver, to learn a trick or two.

M, obsessed with his phone and uncertain about his future, epitomises the aimlessness of the younger generation; Menju, deeply rooted in tradition, religion and family values, reflects the anxieties of older generations striving to preserve their heritage. These generational tensions, grounded in cultural specificity, fuel the narrative’s emotional core. Though the characters are familiar, the film doesn’t flinch away from the presentation of their complex inner desires. The refreshing inheritance conflict plot is an effective vehicle for its astute observations of human nature.

Beyond M and Ahma’s evolving bond, the subtleties of familial relationships are illuminated through M’s family dynamics. Menju’s oldest son, Kiang (Sanya Kunakorn), is too preoccupied with work and his own family, so seldom finds time to visit her home. Her second son, Soei (Pongsatorn Jongwilas), has not been able to find his footing in society, and exploits his mother as an ATM to pay off his debts. Meanwhile, M’s mother—the often-overlooked daughter—finds herself wanting to help but undervalued in a patriarchal society which favours sons over daughters. These relationships highlight intergenerational struggles, from caregiving burdens to cultural biases.

The heavy emotional weight of the film is lifted with touches of humour; tears induced are checked by chuckles. M’s mischievousness, Ahma’s obstinance, as well as society’s absurdities picked up by playful camerawork, add some laughter and depict the realities of life. The scenes in the hospital, supermarket, the Metropolitan Rapid Transit, and Thailand’s busy streets, bring meaning and resonance to the everyday paths we walk. The soothing piano score, punctuated by traditional Teochew opera, strikes the right chords and deepens the film’s emotional impact.

While the film is predominantly in Thai, the use of Teochew by the family reflects their Thai-Chinese ancestry. Ahma scolds M for not knowing Teochew, their mother tongue, a pervasive concern within intergenerational conflict. When M first moved into Ahma’s house, his ignorance in his grandmother’s habits and beliefs caused him to unwittingly violate her vow to abstain from eating beef. While Buddhism does not directly forbid the consumption of beef, the Thai-Chinese consider cows to be a sacred animal. Nearing the end of the film, the reason why Ahma stopped eating beef was disclosed by M to Kiang. Kiang fell gravely ill when he was young, and in exchange for healing, she promised not to eat beef for the rest of her life. The subtleties of cultural and religious experience are brought to life through Pat Boonnitipat and Thodsapon Thiptinnakorn’s masterful storytelling.

Parasite director Bong Joon-ho once famously remarked, ‘Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.’ The barrier in this film does not seem to be just the language, but also the inherent sociocultural context—the challenges of an ageing society and the importance of filial piety—which have been lost on the two The Guardian film reviewers who unanimously gave the film three stars. Its original Thai title, Lahn Mah, which means grandma’s grandchild, is probably a better fitting title which resonates more intimately with viewers.

If Korea’s Parasite (2019) can be likened to Bad Genius (2017), Thailand’s most internationally successful film to date, How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies (2024) is Thailand’s Minari (2020), a similarly intimate and heart-wrenching portrait of family. However, unlike Minari, it did not make the final Oscar cut. How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies is a moving tale about loss and greed, but also about family and warmth—a guaranteed cathartic cinematic experience.

Despite its limited Netflix release, the film is best experienced in theatres. Where better to cry than in a dark room in solidarity with strangers even as you pretend that you’re alright when the lights come up? Don’t forget to bring tissues. And if you don’t already know, Billkin, who plays M, is pursuing a master’s degree in entrepreneurship at UCL. You might just spot him on campus, an autograph opportunity you won’t want to miss.