LEAFF 2021 celebrates its sixth year with a programme of thirty films from celebrated and debut filmmakers. Championing East Asian cinema, LEAFF aims to bring a wide range of cinema to London and offer the opportunity to experience a new culture of cinema.

Mara Dinu reviews the heart-breakingly honest Japanese documentary about an immigration center near Tokyo, filmed using a hidden camera.

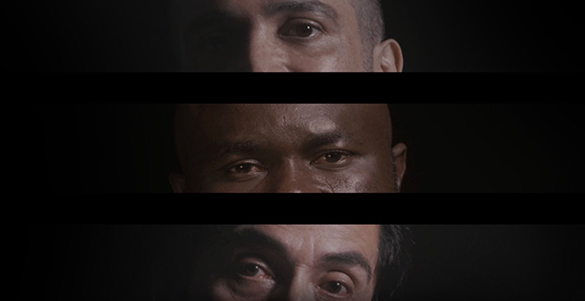

It starts with the blurry image of a man. He is behind a glass wall, in a small white room, illuminated by a cold LED light. He looks devastated. This is the first of many held in the Ushiku detention centre for immigrants whom Thomas Ash managed to interview using a hidden camera. The series of shots and interviews that follow are built on a dark, hidden truth of which even Japan isn’t aware. I thought this documentary would be moving, but it was more than that; Ushiku (2021) felt frightening and deeply disturbing.

In 2019, only 0.4% of applicants were granted refugee status in Japan. There are seventeen immigration centres in the country, one of the largest ones being in Ushiku. 50% of the people in the Ushiku centre, waiting to get their refugee status approved, had resided there for five or six years. The ones who had been living there for just a year or two considered themselves new. The uncertainty of their situation exposed them to constant pressure and stress, making them compare the centre to prison: “If this was a prison, you’d know when you were getting out.” Some of the detainees went to Japan looking for shelter with a tourist visa but were denied entry. Others contacted the Japanese Association for Refugees only to be told that it was complicated to get the status.

In his first interview, ‘C’ confesses that he felt happy there. He explained how there was nothing left for him outside of the centre, that his home had burnt down, and he had nowhere else to go. He said he was happy to have a place to sleep, to eat, with people to talk to. He remained silent for a few seconds, then burst into tears.

Peter was the first to mention the exact strategy they had developed to get a Provisional Release: hunger strikes. If they stopped eating for a long time, long enough that the doctors were required to check on them daily, the guards would start begging them to eat or drink water. They would refuse unless they got the Provisional Release. 40 days of starvation for 2 weeks of freedom. Thomas asked Peter to write down his story for the next time he would visit. Nicholas mentioned the hunger strikes as well: “I started the hunger strike and after 80 days they let me out.”

Naomi, a trans woman, told Thomas about the time she had to witness her friend being beaten to death in front of her in her home country because of their gender and sexuality. She decided to run away to Japan where she could live as her true self. She was assigned to the male immigration centre in Ushiku.

Deniz mentioned his Japanese wife in his first interview and talked about her visits – too short and not enough. Only thirty minutes at a time, making him too sad to bear her leaving.

In Peter’s second visit, he brought three pieces of paper: his story. He was ready to hand it over to Thomas, through one of the guards, as he had previously been allowed to do with other people and other letters. This time, the guard did not let him give anything to Thomas, mentioning an application that he was supposed to fill out prior to the visit. Peter started panicking and crying. When Thomas asked why he couldn’t hand him anything this time, he said: “they know you’re up to something.”

Médication and health services were also discussed. “It’s like you’re a lion in a zoo. We die like cockroaches.” We hear terrifying stories of people complaining about migraines and angry guards forcing them to take some painkillers, only to find them dead the next morning.

Claudio mentioned how he was taken to the eye specialist in handcuffs and how everyone in the hospital was “pulling away” the doctors treating him poorly. He was laughing. He started showing Thomas a series of drawings that he made during his time at the centre. One of them was a hole in a faraway ceiling, a hole opening towards the sun, unreachable. He said that was how he was feeling.

Peter’s third interview was the most painful one – he was crying continuously in atrocious pain, unable to move or speak. They had taken him to the airport after letting him know he was finally able to leave, but they ended up hitting him instead, pulling his arms and twisting his neck. He was left with one of his nails ripped off and his leg bleeding. We see a series of indescribable photos from the event at the end of the film.

Christmas comes and Thomas receives a series of phone calls from the people at the centre, wishing him a happy holiday. Claudio mentions a special steak treat. Peter is still in pain.

Thomas meets Ali for the first time – a friend of Naomi. He was properly interviewed, as he was on Provisional Release after a long hunger strike that made him lose 15kg. He said he didn’t know what to do when getting back. Ali was thinking of another hunger strike, but he felt like his body couldn’t handle a third one. He was unable to gain any weight during his two weeks out. Ali mentioned how he was immediately retained at the airport, right after applying for refugee status. He said thirty people did run away while being on Provisional Release and Thomas enquired him why he didn’t do the same thing. Ali replies, “if I run away, I can’t be here legally.”

Thomas gets a call and finds out that Deniz attempted suicide. He was found and put in the punishment cell – a place Ali mentioned as being painful and isolated, where detainees are held and get their necks twisted. We also see Ali’s state of mind slowly deteriorating as he starts needing mental health support and treatment for depression. He refuses to eat again, even if he is aware of the consequences. “This is a fight between me and immigration. No one knows who will win.”

After a while, Deniz receives his Provisional Release and, with the help of Ishikawa Taiga, manages to address the issues of the detention centres during a meeting with the National Diet. Taiga’s questions about the health insurance and other rights of the immigrants were considered unexpected – the whole situation seemed to have been reviewed as some kind of necessary evil that would help them deal with the integration of immigrants.

During the G7 summit in 2017, Japan was one of the countries that signed guidelines on how to support refugees in their search for safety. Unfortunately, they have since failed in treating them humanely. On the 31st of December 2019, there were a total of 942 detainees in Japanese detention centres for immigrants. During COVID-19, 75% of the detainees were given provisional release.

We see a final series of interviews of everyone during their proper, four-month provisional release. We discover that they are not allowed to work nor have any money while the pandemic gets worse and worse. They are all shattered and devastated, and cannot seem to summon back any memories from Ushiku because it is all too painful. Their uncertain lives keep going, consuming them. Someone mentions that perhaps it would have been better for them to die in their home countries than to suffer in another one. In May 2021, there are still seventy-eight detainees in the Ushiku immigration centre.

Watch the trailer here: