BFI’s London Film Festival is in town! The FilmSoc Blog is back for the 64th edition of one of Europe’s largest film festivals, delivering a first look at the hits and misses of the 2020-21 season.

Kirese Narinesingh reviews Mangrove, the second film in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology, based on the true story of Caribbean protestors and their struggle against police harassment.

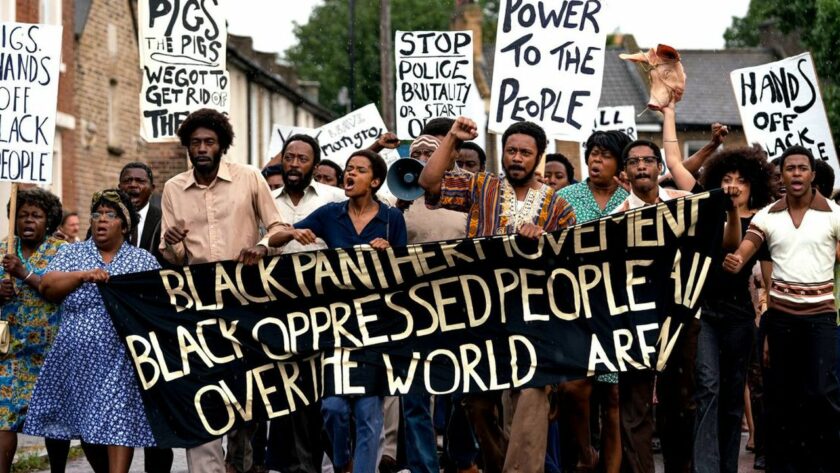

What a relief, to have a film that embodies the Caribbean experience in Britain, without resorting to stigmas and half-hearted forays into Caribbean culture. Mangrove is an expressive film, that captures all the contradictory sensibilities of the Caribbean: from the conversational, energetic heights of protest to the quiet resilience of the family. The film, McQueen’s second in his Small Axe anthology, is above all about community. Offering a filmic rebirth of this vibrant community of immigrants who came to Britain in the post-World War Two era, director Steve McQueen pays tribute to the community’s joys and resistance against their struggles.

The Caribbean restaurant: the hub of a community whose activities include playing the steel pan, cooking their cuisine, mingling with friends and family and inevitably, fending off senseless raids by the police. One of these restaurants was the Mangrove, owned by the film’s protagonist, Frank Crichlow. He’s the reluctant hero turned activist who, along with the other members of the ‘Nine’, were the bulwarks of the community who challenged the racist justice system. If the strength of the West Indian community lies in its most durable characters, these are the ‘Mangrove Nine’. Crichlow, Darcus Howe, Barbara Beese and Althea Jones-Lecointe (Shaun Parkes, Malachi Kirby, Rochenda Sandall and Letitia Wright) are McQueen’s primary protagonists and the defenders of their community’s dignity.

We are presented with two perspectives: that of the West Indians and that of the police. McQueen does well to distinguish between these two different worlds. The jump from the musical, kaleidoscopic culture of the West Indian community to the monotonous blues and reserved tones of the police are made jarring – even more so when the happy, upbeat atmosphere is interrupted by the racist comments of the policemen, who bide their time waiting to disband the Caribbean restaurant’s liveliness. This conflict churns to the point where the ‘Nine’ are wrongfully arrested and the story turns into an intense courtroom drama, where the racial prejudices mingled with the incompetence of the police are exposed dramatically, but effectively.

Thanks to the production designers, Helen Scott and Lisa Duncan, the film excels in creating a complete cinematic world, the Notting Hill of the 60s. It’s so well done that the film feels as if it were actually made in 1968. It’s no wonder that the best scenes are those that showcase the community’s day-to-day living. Although it’s obviously a serious film, that doesn’t mean it isn’t very funny and endearing at times, especially if you understand the lingo. The characters sing Mighty Sparrow’s iconic “Jean and Dinah,” a song known to most Trinidadians, they read The Black Jacobins and they play the steel pan. Perhaps this is also a grab at nostalgia? Notting Hill of our post-gentrified present does not resemble these moments in time. Nonetheless, for a Trinidadian like myself, it’s a welcome veneration.

My only reservations are the imperfect accents, and at times, incorrect expressions, which may only be evident to other West Indians (Trinidadians would never say “goat curry,” it’s “curry goat”). [1] Moreover, the film’s balancing act of originality and conforming to generic tropes tips to the latter end of the scale as the story reaches its second half. The courtroom scenes are admittedly conventional and fall into old formulas comprising vehement, passionate speeches. But I’m being nit-picky. The performances of Shaun Parkes, Malachi Kirby and Letitia Wright lack any insincerity. Their confusion, frustrations and pain in the face of unjustified treatment are incomparable and thankfully, genuine. Mangrove is a conscious effort towards dramatising the vicissitudes of life in London, putting the Caribbean experience at its forefront.

There aren’t that many films that celebrate the Caribbean community in London. Films that came before it, like Horace Ové’s Pressure, end on cynical notes, whereas Mangrove forgoes the cynical for a panegyric exercise in optimism and grudging hope. The “stench of British colonialism” (Darcus’ words) may still be a constant source of torment, but the community stays constant in its resilience. It’s a cogent message that mustn’t be forgotten, especially in times when racial inequality is as glaring as ever before.

[1] This is a bit of an inside joke: there are many amusing debates between the Trinidadians and Guyanese about which is the correct way of saying it. I, for one, prefer “curry goat”, but I’m biased.