Diego Aparicio takes an exciting look at the 2017 Palme d’Or-winning satirical drama.

This review originally appeared on the author’s film blog, Observancy. It has been slightly modified.

Ruben Östlund’s follow-up to his wickedly funny Force Majeure (2014) is a hilarious satire not only of the modern art-world, but of today’s society in general. Winner of the 2017 Palme d’Or, nominated for this year’s Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and gathering an impressive total of six European Film Awards, The Square features some of the year’s funniest and most memorable moments in cinema.

The Main Exhibit

In an opening scene that sets the tone for the ensuing hilarity, journalist Anne (Elisabeth Moss) interviews the respected curator of a Swedish contemporary art museum, Christian (Claes Bang). Attempting to make sense of a rather pretentious exhibit description, Anne is left all the more confused by Christian’s attempts to explain the artworks, who is clearly making things up as he goes along. This hysterically funny exchange is followed by a scene in which Christian has his phone and wallet stolen by a pickpocket, and we look on as his desperate actions clash with his apparent ideals. Two stories unfold in parallel: one focusing on Christian as an individual, the other on the role he assumes in public. All the while he is left in charge of promoting a new exhibition which has one particular piece of art at its centre, ‘The Square’: an installation inviting the public to an act of altruism.

Review

Despite some scenes that slightly outstay their welcome and perhaps trying to do too many things at once, this satirical drama by writer-director Ruben Östlund boasts a hilarious script, with several memorable scenes and some very clever directing. The Square plays with the idea that, despite their apparent appreciation for the arts, people from the high society can certainly still be very superficial and uncultured. Power games between genders and social classes are also satirised, as is the media’s often detrimental influence on art. Östlund also seems to be making a comment on the untrusting, selfish stance people often adopt in their relationships, and the lack of honesty and intimacy this leads to in society. The film’s laudable production design did not go unnoticed at the European Film Awards, and neither did Bang’s strong lead performance. The soundtrack includes some interesting choices, which often add a further touch of comedy to the film. Apart from offering a few good laughs, the film raises questions of social importance that even touch the existential at times. It may not do so very coherently, but it does some interesting things that largely compensate for that.

The Inspiration

At Curzon Mayfair last month, the director revealed that the story was inspired by true events that took place in Gothenburg, around the time he was working on his 2011 film, Play (2011). What Östlund witnessed stayed with him: young boys in a shopping mall robbing other young boys in the presence of adults. What struck him most about this, he said, was that on only a small number of occasions did the victims receive any help, or indeed ask for it in the first place. Östlund discussed the incident with his father, who told him that parents used to be more trusting of other adults with their children ‘back in the day’, a discussion repeated in The Square between Christian and his daughters.

And so the idea occurred to Östlund and his friend, Kalle Boman, ‘to create a symbolic place where we’re reminded of each other.’ It was only after the success of Force Majeure that a museum in Värnamo agreed to host an installation of a square, much like the one in the film. A recent interview with Östlund for The Guardian revealed some of the things that went on within the square: ‘On the opening night, drunken youths stole the plaque. Afterwards the square became a base for buskers, beggars and protesters. Office workers gathered to eat lunch on sunny days. Lovers proposed within its borders. How it is used is up to the people of the city. If they abuse it, it reveals something about them. If they treat it well, it says something interesting, too.’

‘Humans have the ability to create fictions that change their behaviour. Like a pedestrian crossing,’ Östlund said at the Q&A. In the same way, the square in the film can be thought of as ‘a humanistic traffic sign’. The punishment for not helping someone in need inside ‘The Square’ is shame.

Squares Within The Square

‘Trust is something you give to your kids by saying “you can trust other adults”. If your parents tell you that, then that’s what you feel towards others in life’, Östlund said at the same Q&A session in Mayfair. On several occasions in the film, the writer/director seems concerned with the importance of family in society’s struggle to become more caring. Christian is a divorced father of two and, though his marital status doesn’t necessarily say anything about the society he’s part of, it does affect his children’s upbringing.

When Christian’s daughters first make an appearance, the camera pans onto an art piece on his apartment wall, and the audience is left to admire square within square within square inside the frame, a lingering shot revealing what could be one of the film’s most important moments. It asks: how does Christian, as a father, inspire his children to be trusting, generous, and caring?

He loves his daughters, no doubt, but he also seems to handle parenting quite poorly at times: he loses his temper a bit too easily; he loses sight of his daughters at the mall (and asks a homeless person to guard his shopping bags while he looks for them, when none of the rich people will help him); and he abuses his power in front of them, pushing a young, working-class boy down the stairs, refusing to take responsibility for his earlier misbehaviour.

In fact, it is the father that is taking life lessons from the children. Despite his position, Christian does a poor job at promoting ‘The Square’, both as a piece of art and as an ideal. A visit to see his daughters perform synchronised gymnastics appears to teach him more about community than art ever does in this film. The sports court where his daughters spend time with their coach is outlined in white lines, and a quadrilateral is projected onto the frame, much like ‘The Square’ itself in an earlier scene. It is only after seeing his daughters and their team supporting one another on that court that he decides to apologise to the boy he mistreated.

When Christian drives to the building where the boy lives, his daughters want to accompany him. The director said that the (initially longer) scene where the three of them are climbing up the stairs to the boy’s apartment was written as a sort of pilgrimage that all three of them had to make; it’s something that they do together, in a team effort to make up for Christian’s mistakes. Interestingly, it evokes that antecedent scene on the staircase in Christian’s building, and encourages a comparison between the two social classes once more.

First World Problems

Alas, Christian doesn’t get the redemption he seeks, and has to live with his shame. At the Q&A, Östlund recounted the plot of a poem that inspired the film’s ending. Written in the 1900s by an upper-class Swede, the poem tells the story of a game of marbles in which the narrator wins five marbles from a poor boy, using the fifty marbles that he already owned (giving him a distinct advantage). In time, the initial pride and sense of power that the narrator feels are replaced by a sense of shame at his privilege. This is telling of a poem written at a time when social classes were shifting in Sweden, and the middle class started having access to education. The narrator seeks out the boy, in the school yard and in the neighbourhood, but never finds him. Years later as an adult, he remains tormented by these memories and has to live with his guilt.

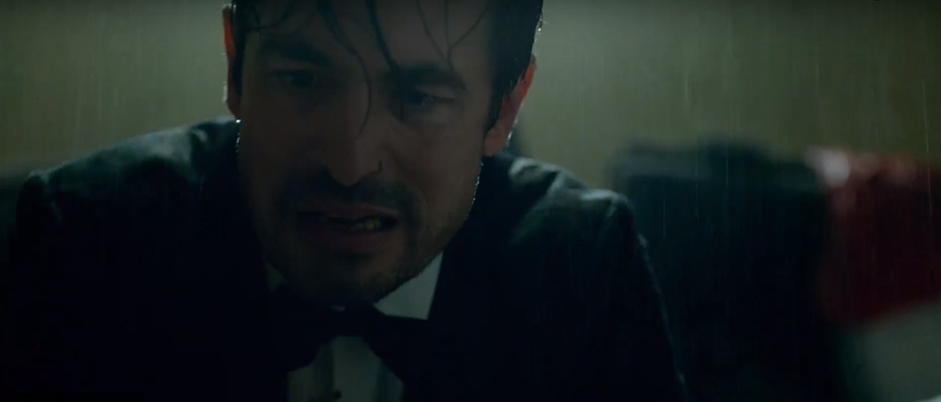

Christian is much like the narrator of this poem. After pushing the young working class boy down the stairs of his apartment building, he remains haunted by the boy’s cries for help, having initially ignored them. Desperate to make amends, he searches through a sea of garbage bags for a note with the boy’s phone number. This iconic scene, with Christian on his hands and knees in the pouring rain, consumed by endless piles of rubbish, is a suggestive metaphor for how poor his inner world is in contrast to the expensive suits he’s always seen wearing.

Monkey See, Monkey Do

‘Soon you will be confronted by a wild animal. Convey fear, and the animal will hunt you down. Remain perfectly still, and you can hide in the herd, safe in the knowledge that someone else will be the prey.’

Terry Notary’s jaw-dropping monkey performance combined with that little prologue (above) makes for a unique and immersive existential experience; one that is only accentuated by the grandiose dining hall setting and all the bystanders of high society sitting still in almost uninterrupted silence. But what’s with the monkey? And why does Anne have a pet primate in her apartment? Apart from being excellent comical devices, these elements also serve as reminders that apism is abundant in our societies: and if we’re all just copying each other’s behaviours, we’d better be setting examples that are worth imitating in the first place.

A Bit of Trivia: the Lola Arias Controversy

The Square (as an artwork) was conceived by Östlund and Boman in reality, but is attributed to an Argentinian artist called Lola Arias in the film. In fact, Lola Arias is the name of an actual Argentinian artist and filmmaker, who earlier this year presented her documentary, Theatre of War, in the Forum section of the Berlinale. Although Östlund claims he did not know of Arias when writing the script, he says the artist had been informed that her name would be used prior to filming. Arias herself remembers a somewhat different story. ‘It has hurt my reputation as an artist because I am associated with an artwork that is not mine and that I dislike… I was shocked when I saw how they used my name without consent.’ Just the type of conflict the media love to promote art with.

A slightly modified version of this piece can be found on the Curzon Blog. Many thanks to Ryan Hewitt for all his helpful suggestions.

The Square is out now in UK cinemas. Check out the trailer: