Nutshell: A chic polished departure.

Aftertaste: A refreshing, ice-cold glass of blood orange juice—its initial sweetness bursting with the vitality of life, followed by a subtle bitterness that lingers on the palate, encapsulating the inevitability of death that makes life just that much sweeter.

Who’s cup of tea? Those who contemplate death as often as they do life.

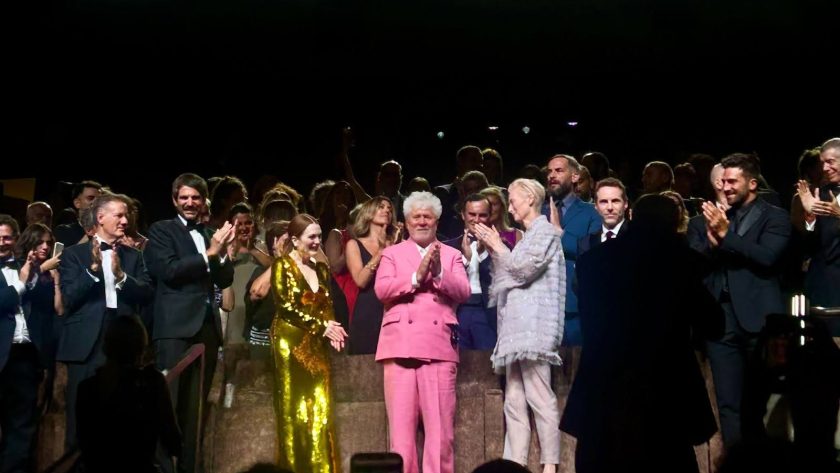

On the final night of the 81st Venice Film Festival, the coveted Leon D’oro was awarded to The Room Next Door (2024), the latest in the long line of critical darlings directed by Pedro Almodóvar. The film premiered on the 2nd of September, and miraculously I was able to attend – if you want to hear more about my festival experience, check out my article here! The premiere concluded with an 18-minute standing ovation, sparking a certain debate on its excessiveness. Yet, having been there cheering myself, I can assure you it felt well-deserved. The ovation extended past appreciation for the film to a celebration of Almodóvar’s iconic and ever-evolving career. The director – dressed in a vibrant pink suit, its gold accents a glimmer of what was to come – descended the stairs of the Sala Grande alongside his leading actors, Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore, graciously thanking the audience for their warm reception. It was a touching tribute to a Spanish legend and his remarkable body of work.

From my first encounter with Volver (2006), thanks to my Spanish A-Level class, I have been hooked on the Spaniard’s distinctive filmography. Over time, I have found myself viewing the world through an Almodóvarian lens- sporting his signature stubborn reds, spotting his gorgeous interiors and subtly supporting anyone resembling his strong, complex, ever so slightly melodramatic female leads. I approached his first English language feature with some reservation, fearing the loss of his quintessential Spanish flare. There was no need to worry. The Room Next Door delivers these defining tropes with deft ease. It felt 100% Almodóvarian in all the best ways.

The screenplay is an adaptation of Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through [2020] recounting a poignant tale of female companionship between two older women who reconnect in the face of terminal illness. Former war reporter Martha (Swinton) has confronted mortality many times during her career. Yet, the prospect of a slow fade from dignity, her course of chemo stripping away the small pleasures of life day by day, is presented as sterile and undignified.

The film makes a clear case in favour of legal euthanasia access through Martha’s assertive decision to end her life stating ‘I think I deserve a good death.’ She resides in the help of her friend Ingrid [Moore] to assist her in her euthanasia by asking her to stay in the room next door, to provide her comfort during her final moments. Ingrid struggles with the moral and legal implications of this decision but prioritizes her role as a loyal friend above all else. Their deep friendship flourishes on screen, brought to life by the magnetic chemistry of Swinton and Moore. The film treats the often overlooked narrative of female friendship among older women with such grace and respect rarely seen on screen. It makes me appreciate how Almodóvar is one of the only male directors who can approach such themes with genuine sensitivity and profound insight.

The central narrative is tempered by telenovela-style flashbacks, enriching its pacing and visual experimentation. A dramatic death scene seems painted with the same brush as Andrew Wyeth’s iconic ‘Christina’s World.’ Each frame of the film resembles a carefully crafted painting—marked by perfect symmetry, vibrant colours, and a cohesive aesthetic. The set design echoes Edward Hopper, notably referencing his 1963 painting “People Lying in the Sun.” Swinton’s outfits add another layer of visual intrigue, just as the introduction of her dual role in the final lends the film the theatricality we’ve long come to expect from the director. Only an Almodóvar film could make terminal illness look so chic.

The only prominent male character in the film is Damian Cunningham (John Turturro). An ex-lover of both leads and an environmental academic, his role facilitates Almodóvar’s increasingly frequent political commentary. Damian is disillusioned with his son for having a third child amid a climate crisis, criticising an addition to a world believed beyond repair. He sees the planet as a terminally ill patient, much like Martha. But the film does not bow to this perspective of despair. Their fates being intertwined, the vibrancy with which the film depicts Martha’s decision implies that while the world may appear to be on the brink of undignified loss, positive change remains possible.

And so, like Almodóvar himself, hope persists.