Oscar McFie Lyons draws the connections between Spike Jonze’s Her and Sofia Coppala’s Lost in Translation, unearthing what the interplay between the once married pair of directors could reveal about their works.

Some filmmakers exist in perfect conversation with one another. While outwardly they appear to construct depictions of reality apparent to casual observers, they nonetheless remain intimately and thus exclusively connected. One decade removed from the release of ‘Her’, itself a decade on from its emotional partner ‘Lost in Translation’, I wish to explore the delicate yet delightful interplay between the two films to better understand the creators’ intentions behind their films.

/1/ Background

Filmmakers Sofia Coppola and Spike Jones, respectively, are standard-bearers of American independent cinema. They are also ex-partners. More pertinently, they have both reflected on their relationship to one another through the medium of film. I hereby set myself the task of writing about this cinematic relationship with dedication, without being salacious in the process. This is because both movies readily serve as their respective exploration of their relationship to one another. It is a profound instance of artists writing from what they know. More than that, the ambiguity expressed through the pervasive loneliness of each film’s protagonist serves to establish a crucial through-line which is ripe for exploration. Principally, the role-playing of shared memories, and how these two portrayals of an experience communicate with each other.

/2/ Content

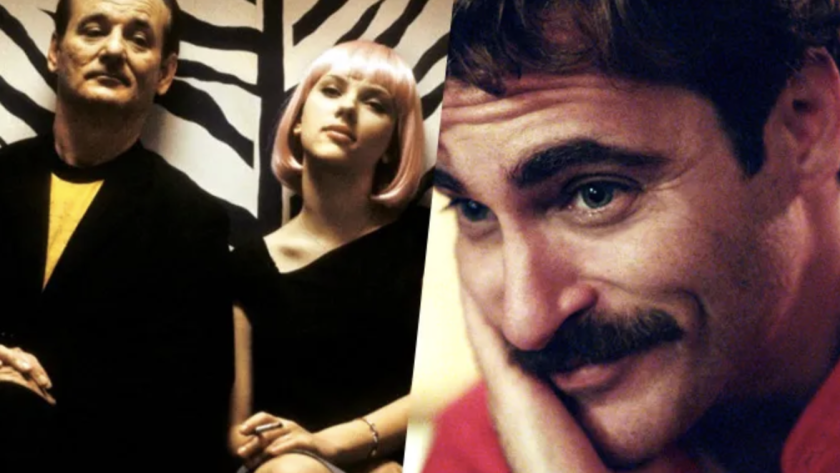

‘Lost in Translation’ appeared in 2003. Gently, too. This is attributable to its minimalist palette fostered by a low-budget, small-scale production. What emerges is a distinctly intimate portrait of isolation in a far-removed city that denies and also encourages connection. It is in this landscape of knowing-unknowing that Coppola places her two protagonists, Bob Harris and Charlotte. The former, played by Bill Murray, is a fast-fading movie star now reliant on international sponsorship deals to support a domestic life from which he is increasingly estranged. For example, you can witness his failure to recall his son’s birthday in the film. More importantly is the filmmaker’s spiritual protagonist, Charlotte. In a statement performance, seventeen-year-old Scarlett Johannson presents a character equal parts playful and solemn, fierce yet vulnerable. Crucially, Charlotte is also unhappily married. Her husband is the career-driven John, amusingly portrayed by Giovanni Ribisi, who appears unsympathetic to his young wife’s feelings in the face of various career opportunities. More intriguing still is the fact that John is a music photographer, much like Jonze in real life is an accomplished director of music videos. It is in this mode that Coppola takes the drastic decision to make the personal public; to recapture real situations in a reconstructed world.

‘Her’ echoed many of the central themes laid out by Coppola. It is similarly an accomplished paean to isolation and loneliness whilst also extrapolating the effects of modern artificiality through an underappreciated yet delightfully captured cityscape. It is one part Los Angeles, another part Singapore; in total a genuine marvel. Its protagonist, Theodore Twombly, is a curioso: dressed in matte, autumnal colours, he works as a greeting card writer for an otherwise benign company. No matter the hours he spends carefully crafting notes of immense intimacy, he is destined to return, alone, to an empty and unlit apartment each night. However, Theodore is divorced. We are introduced to his ex-partner, Catherine, by means of various email communications from her lawyer imploring him to finalise their separation. However, the introduction of Samantha, an operating system crucially voiced by Scarlett Johansson, uproots our protagonist and prompts careful reconsideration of his life’s direction. Mirroring Theodore’s deliberation is the fact that Jonze granted himself a decade to fully reflect on the consequences of his own divorce. Through repeated callbacks to his and Coppola’s relationship – both the good and bad parts – we are at pains to discover that our protagonist is forever tormented by his past.

/3/ Significance

Coppola’s interest in the lived experience of Charlotte proceeds from her infamous opening shot. Crucially, her body is facing away from its audience, an open invitation for identification with the unknown. Throughout the opening thirty-minutes – during which Charlotte and Bob remain independent – we observe Charlotte as she embarks on purposefully mundane, everyday actions. From refitting a bedroom light to taking a bath, Coppola gives Charlotte a personal touch that transcends mere storytelling. Or so it appears to an observer who notes an endearing focus on the banal and trivial which can only be rendered valuable by those with past experience. The very notion of a partner suffering from their partner’s persistent absence could appear little more than a romanticised Hollywood cliché were it not for the ‘irreconcilable differences’ referenced in their divorce filing.

And while Coppola herself is now, rightly, regarded as a one of the most prominent American directors in history, in 2003 the then-director of ‘The Virgin Suicides’ was arguably better known as a) the daughter of Francis Ford Coppola and b) partner to the visionary behind ‘Being John Malkovich’. I do not mean to excavate the past, but it is worth considering what this means for the movie. This has humorous implications with the introduction of Kelly, played by Anna Farris, who serves as a stand-in for Cameron Diaz. This transcends skepticism, instead pointing towards a further aspect of reconstructed reality since Coppola’s suspicions of Diaz towards her then-husband were well-documented. Yet there is much more from her own life that Coppola brings to the film. From the outset, the notion of two lost souls connecting in a far-off place ties in with concepts explored in various works from ‘Casablanca’ through to ‘In the Mood for Love’. However, the grace that is granted to these two characters to explore their relationship with one another, despite differences in age and commitment, is testament to the director’s considered approach. It is a true sign of humanist intelligence, an ability to capture what is essential between people without the need to spell it out in clunky dialogue. While it is clear Coppola is not advocating infidelity outright, she is exploring the limits of our commitment to one another when our own identity is at stake. The challenge is in negotiating between these two forces without losing sight of what is most important.

‘Her’ bears similarly striking personal marks. This is underscored by the fact this was the first movie that Jonze wrote independently in a five-month writing blitz. In contrast to ‘Translation’, however, we are granted a more long-form conversation between the two, now ex- partners. While Coppola sought to capture two partners unable to communicate in ways besides fractured moments together, Jonze captures the divorce in excruciating clarity. It is a simply shot scene, yet one that forbids extravagance in favour of a pared-back conversation between two characters as they wrestle with one another and the reasons for their relationship’s fractious end.

Jonze induces Theodore to appear initially critical of Catherine, citing her cold nature and aversion to affection, yet purposefully encourages a more reticent and apologetic perspective soon after. This is truly effective, unsettling storytelling in ways that extend beyond the actual film. In various montages, Jonze established a longing for a relationship that simply no longer exists. It is crucial to note that, notwithstanding the centrality of Theodore and Samantha’s relationship, girlfriend-turned-friend Amy is the person whom our protagonist ends the movie alongside. Amy is somehow grappling with the end of her relationship as the movie itself unfolds, for a simple and benign reason: shoes, and their placement in the home. Much as in ‘Translation’, a relationship is not defined by moments of clear loss or gain. Rather, we as an audience are invited to consider what it is that we owe our former partners as much as we owe to ourselves. And to question whether our commitments are uneven to the point that personal autonomy is being ceded thoughtlessly.

/4/ Epilogue

In writing this piece, I have been encouraged to consider what it means for an artist to craft an alternate world. Is it for safety, to encourage a world open to their own ideas? Or is it for their own memory, to encourage revised understanding? Or is it to communicate ideas that are often wordless? Both movies explored here are intimate portraits of assorted people who, for reasons numerous yet small, are in doubt over what they owe one another. The fact such important contributions to modern American cinema have been given by two filmmakers so intimately connected invites critical thought. For it is worth noting that, in two filmmakers well-known for the care and consideration they grant their projects, it is unlikely these films will not have been well-thought out. What this means as a communication between filmmakers is fated to be purely speculative, yet worthy of exploration.