Shayeza Walid reviews the perfections and the problems in 2021’s biggest sci-fi blockbuster Dune, starring Timothee Chalamet and Zendaya.

I was probably one of the last people to watch Dune after its release in late October. However, in my defense, I was adamant on finishing the novels before viewing the film, and despite their gargantuan length, I must say that I stick by that decision made — because, as you might have heard, the sci-fi world of Dune and its intricate mechanisms is, well, vast and complex to say the least. So, some background knowledge truly and perhaps even prescriptively, helps. Yet, now having watched the almost three-hour saga, I accept without hesitation that aesthetically, every minute was worth the wait, and indeed, the hype. Nonetheless, from a plot-perspective, I also have some serious criticism of the exceedly orientalist representations embedded in the narrative.

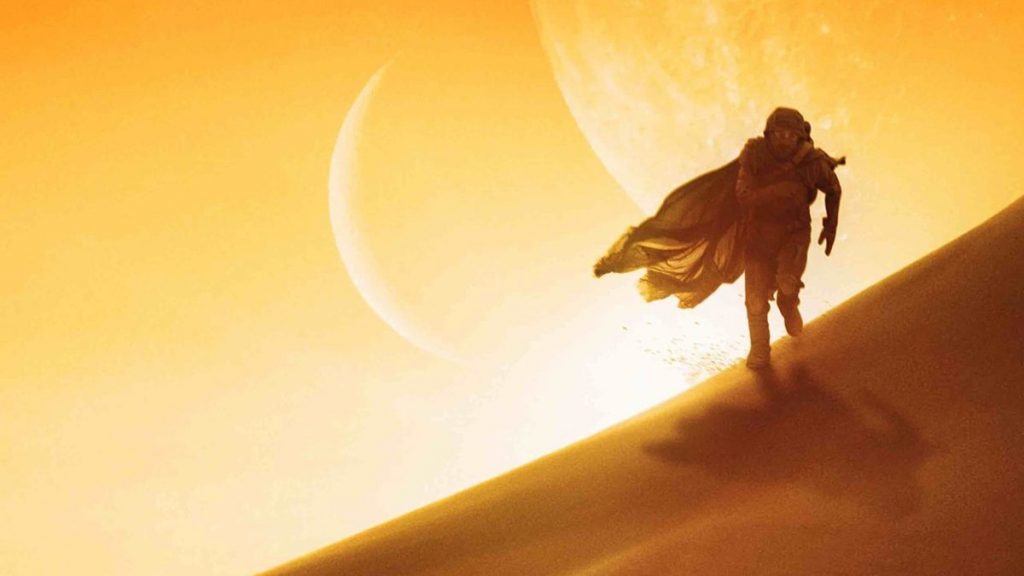

It is remarkably rare for one to call a film perfect, me least of all. However, Denis Villenueve’s much awaited adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novels, takes on and fulfills the monumental task of recreating the expansive world of the novels seamlessly. What we are left with in the end, is an aesthetically immaculate film, both captivating and visually engulfing.

The plot of the film is straightforward if one has read the first instalment of the series. However, without having done so, some context is much needed — and admittedly tremendously helpful — in appreciating the work of both Villeneuve and the film’s cast. In Dune, we find ourselves in the distant future, amidst a interstellar feudal society in which various noble houses control planetary fiefs. The story follows young Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) whose family accepts stewardship of the planet Arrakis, land of the Fremen. While this planet is an inhospitable and sparsely populated desert wasteland, it is the only source of ‘spice’, a drug that not only extends life and enhances mental abilities, but is also necessary for space navigation, requiring a kind of multidimensional awareness and foresight that only spice can provide. However, as this spice can only be found on Arrakis, control of the planet is coveted. We see how the different factions of the interstellar empire confront one another in a struggle for the control of Arrakis and its resources, and Chalamet’s character is at the forefront of this quest, hoping to fulfil his father’s desire to bring peace to Arrakis. By the end of Dune, which only covers the first half of the first novel in Herbert’s series, we see Paul attempt to do exactly that, as he and his mother join the Fremen in Arrakis.

Chalamet shines, but is far from the only notable performance. Indeed, Dune boasts an all-star cast; including Oscar Isaac as Paul’s father Leto Atreides, Rebecca Ferguson as Lady Jessica, Jason Mamoa as Duncan Idaho, Josh Brolin as Gurney Halleck, Charlotte Rampling as the Reverend Mother Moheim, and Zendaya as Chani, a member of the Fremen (worth mentioning despite her grand 15 minutes of screen time), all of whom seem to have perfected their characterisation with a deep sense of gravity and distinct energy.The performances, in combination with the sheer grandiosity and flawlessness of the cinematography make this film a truly immersive experience.

Yet, despite its sincerely attractive qualities, Dune is piercingly Orientalist. Of course, the premise of the novels are orientalist and colonial to begin with. However, I do believe that rather than improving the novel’s audacious, and indeed Orientalist, engagement with the ideas and experiences of the non-western cultures that are depicted or inspire characterisations in the novel (i.e: Islam and the MENA region), the film waters down the novel’s specificity. Trying to avoid Herbert’s apparent insensitivity, the movie subdues most elements of Islam and the Middle East and North Africa. The film treats religion, ecology, capitalism, and colonialism as broad abstractions, stripped of particularity.

Sure, in current times, when cross-cultural appreciation and understanding are heralded, the novel’s themes may be deemed wrongly exotic. However, this blatantly contradicts Herbert’s well-known goal to counter what he saw as bias, and recognise how much Middle Eastern cultures and “Islam […] has contributed to Western artistic culture.” So really, the film’s diluting of such cultural elements just ends up relegating the influence of Islamic and MENA culture in Dune to exotic aesthetics. In attempting to play it safe, the film becomes even more Orientalist than the novel.

While the novel challenged fixed Orientalist categories such as ‘East’ and ‘West,’ the film opts for binaries: it codes obliquely Christian whiteness as imperialist and non-whiteness as anti-imperialist. Even the use of language is oddly conspicuous. The Fremen sound like a 21st-century, Americanized caricature of a generic foreign accent. Moreover the novel’s use of elided Arabic is removed. Even when Arabic and Persian appear, they are poorly pronounced. While for some reason, the movie’s characters speak modern English and Mandarin perfectly.

Dune’s orientalist issues are rather abundant. Nonetheless, I do not believe it should necessarily be put down because of these. Obviously, neither Villeneuve nor the production team sought to offend Muslim or MENA people. And, in the end I will say that, in spite of the orientalist thematics imbricated in the film’s narrative, Dune’s aesthetics profoundly redeem it. If cinema really is about consuming and appreciating the evocative nature of the visual moving-image, Dune is quite emphatically excellent.

Dune is out right now: