Editor-in-chief Pihla Pekkarinen criticises this depiction of Guantanamo Bay for its milk-toast condemnation of torture.

I must admit, I went into The Mauritanian prejudiced. A legal drama concerning 9/11, the US military and their extensive war crimes? No thank you. Not only has the ‘true story’ format been done to death, and the idea of another film about the brave Americans protecting their country against those evil Muslim people frankly nauseating, but I also struggle with the strangely industry-specific films that seem to be popular nowadays. Jargon isn’t my thing. But I love Jodie Foster, and I was interested in a British production of a U.S. scandal from the U.S. perspective, so away I went.

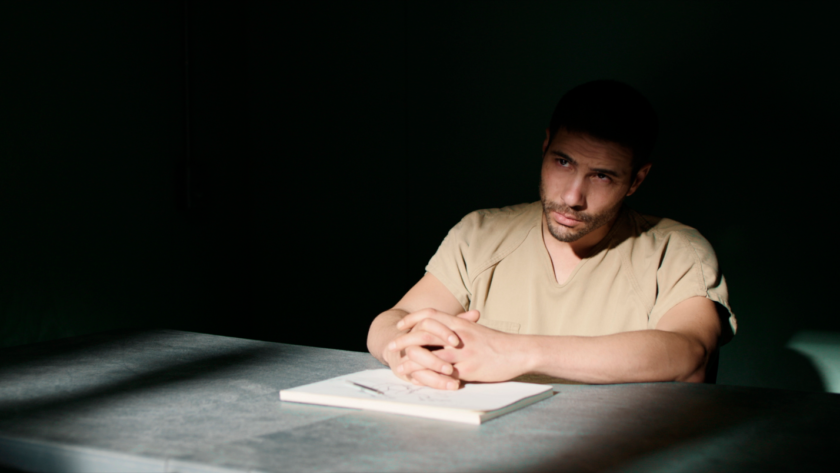

Some of my fears were confirmed. We open with the text “This is a true story”, a classic cheap way to inject more emotional gravitas into a film. The Mauritanian begins with the arrest of Mohamadou Ould Salahi (Tahar Rahim) in the middle of a party. Cut to several years later, and he is being held without charge at the Guantanamo Bay detention centre — a U.S. base established to skirt U.S. laws surrounding imprisonment without charge or trial, notorious for the torture and inhumane treatment of its prisoners. It’s still open, in case you were wondering. Salahi is held under suspicion of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, but with no charges against him and no evidence to speak of, his detention is unlawful. Cut to New York, where Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster, who won a Golden Globe for this role) agrees to take on his case.

The film plays across two timelines: 2005, with Hollander and her associate Teri (Shailene Woodley) preparing for a legal battle against military prosecutor Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch with an astonishingly consistent Southern accent), and the years before, tracing the story of Salahi’s detainment. The Mauritanian uses a 4:3 aspect ratio for the scenes set in the past. The choice seems mainly practical, given the lack of any visual difference between these two timelines (same character, same prison, same uniform), but does occasionally help induce claustrophobia in the viewer and thereby encourage her to empathise with Salahi.

The film offers up some interesting nuance in its characters and their perspectives. At one point, Teri uncovers a letter, signed by our protagonist, in which he confesses to recruiting Al-Qaeda members. When she voices her horror, Hollander tells her to “get out” if that information changes her willingness to represent Salahi. Hollander believes, with her whole heart, in the right to counsel for anyone, including murderers and war criminals, whereas Teri feels her morals go against representing someone like that. But of course, Salahi is not guilty, and in a bland conclusion the characters don’t actually end up needing to consider the morality of who they choose to represent. Allowing for more moral nuance would have made for a more interesting film.

The Mauritanian serves as a good reminder of the horrific history of U.S. prisoner abuse, for anyone who might have forgotten. As mentioned, the Guantanamo Bay detention centre remains open to this day, despite Obama’s campaign promise to close it in 2008. At the end of the film, Salahi declares that he forgives all his torturers and abusers, essentially saying ‘everything happens for a reason’, and that now that he is in court he knows that the sentence will be just. This is really my main frustration with the film: the insinuation that somehow the U.S. military is a good institution, the U.S. is a nation of justice, that they just made a mistake. An angry prisoner, or even more interestingly, a guilty prisoner, would have made for a more sincerely confrontational film. Despite its graphic torture scenes and seemingly open condemnation of ‘enhanced interrogation’, this film inadvertently plays into the same narrative that has allowed Guantanamo to stay open all this time: that bad guys deserve to be tortured. That, in Salahi’s case, they made a mistake because he was innocent, but if he had been guilty, it wouldn’t have mattered. If he had been guilty, he wouldn’t have deserved dignity or legal representation. In the end, The Mauritanian doesn’t actually force us to confront anything, it just gives us the illusion that we are.