FilmSoc President Diego Collado reviews the documentary chronicling Terry Gilliam’s journey to making The Man Who Killed Don Quixote as part of our Raindance 2020 coverage.

| En resolución, él se enfrascó tanto en su lectura, que se le pasaban las noches leyendo de claro en claro, y los días de turbio en turbio; y así, del poco dormir y del mucho leer se le secó el celebro de manera, que vino a perder el juicio. Llenósele la fantasía de todo aquello que leía en los libros, así de encantamentos como de pendencias, batallas, desafíos, heridas, requiebros, amores, tormentas y disparates imposibles; y asentósele de tal modo en la imaginación que era verdad toda aquella máquina de aquellas soñadas invenciones que leía, que para él no había otra historia más cierta en el mundo. | In short, he became so absorbed in his books that he spent his nights from sunset to sunrise, and his days from dawn to dark, poring over them; and what with little sleep and much reading his brains got so dry that he lost his wits. His fancy grew full of what he used to read about in his books, enchantments, quarrels, battles, challenges, wounds, wooings, loves, agonies, and all sorts of impossible nonsense; and it so possessed his mind that the whole fabric of invention and fancy he read of was true, that to him no history in the world had more reality in it. |

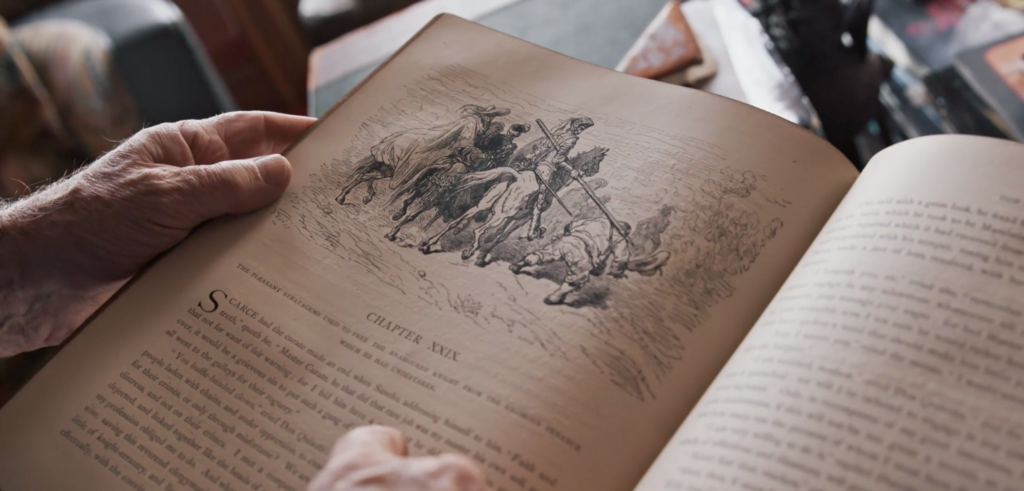

One’s main thought after watching “He Dreams of Giants” is the following: Terry Gilliam is someone that intensely believes in his artistic vision. He will stop at nothing to develop the images that he sees when he doodles with his eyes closed, even if that means losing millions of dollars in the process. Thus, it is not surprising that he was captivated by the tale of Don Quixote, where the protagonist fights everyone that questions his sanity in order to create and live in his own fantasy world, composed of the ideas borrowed from chivalric romances. Gilliam himself is aware that he is almost alone in his fight, accompanied only by Doré and the beautiful illustrations that first captivated him. He is also conscious that he is no longer an “A-list” director with the lavish budgets that he could once get, that he has lost too much money for Hollywood to care about his crazy ideas anymore, but this does not stop him. He is determined to keep amazing people with his unique creative vision, even if his films have gotten noticeably worse with time.

It is saddening to see all of the pain and hardships that he went through for a film that, while good, is far from revolutionary. The Man who Killed Don Quijote was very entertaining, but it simply did not live up to the expectations. But this is the precise reason why the documentary is so stimulating. A project thirty years in the making that will probably only be remembered for its troubled production, rather than for the final product, perfectly captured by two documentaries that give a rare insight into the complicated world of big productions. It is a great tale to learn from when you are an aspiring filmmaker, as most of us are in FilmSoc, but it is also important to remember something: he made the film.

| Estos pensamientos le hicieron titubear en su propósito; mas, pudiendo más su locura que otra razón alguna … prosiguió su camino, sin llevar otro que aquél que su caballo quería, creyendo que en aquello consistía la fuerza de las aventuras. | These reflections made him waver in his purpose, but his craze being stronger than any reasoning, he made up his mind … he pursued his way, taking that which his horse chose, for in this he believed lay the essence of adventures. |

The documentary stresses this persistence and repetition by cleverly integrating behind the scenes footage from previous iterations of the film, constantly reminding the viewer that this is a project that might have gone on for too long. Even when everyone said to him that he should leave it be, Terry Gilliam continued to insist, and he eventually finished it. Yes, Amazon pulled out of US distribution, and the film only made $2.4 million dollars at the box office against a €16 million budget, but he did it, and that is probably more than what most of us expect out of a filmmaking career in an industry dominated by remakes, sequels and superhero films. Whilst indie films are now more important and affordable than ever, as Gilliam notes in the documentary, you cannot keep making films that are not seen. It is undoubtedly disheartening to make a film that is forgotten quickly after its release, even if its artistic qualities surpass other more heavily marketed products, and although it might be useful for a creator to finally pour one’s ideas into a finished production, you cannot keep going in the film industry without some positive results.

He Dreams of Giants plays with this concept throughout the entire documentary: it is pessimistic at times and optimistic at others. Can film as a medium really allow the auteur to fully express his vision? The collaborative aspect of film and the big resources needed to accomplish this hinder absolute freedom, but the conclusion of the documentary is nonetheless a very positive one. Gilliam constantly reminds us that if we have a need to express, to put into moving images those characters and settings that we constantly daydream about, we have to go out and do it, even if it takes us a long while and we have to make some compromises throughout the way. Most creative projects are worth fighting for, he says, even if they might bomb in the box office, even if they do not reach massive audiences. “It is you and the idea, that’s it!”

He Dreams of Giants is nominated for Best UK Feature and is screening online for free on October 31 and November 2. Watch the screenings here:

https://cinema.raindance.org/film/he-dreams-of-giants/?instance_id=1294