Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) is an unflinching commentary on police brutality, racial inequality, and the alienation of marginalised youth within France. Set over 24 hours in a Parisian banlieue, a suburban neighbourhood beyond city boundaries (Onur, 2024), La Haine follows the violent police assault of a young Arab boy and the lives of three young men—Saïd, Vinz, and Hubert—as they navigate escalating tensions with law enforcement. Kassovitz’s use of symbolism and cinematic techniques amplify the tension between authority and the disenfranchised, reinforcing the film’s critique of institutionalised brutality. Through recurring motifs, black-and-white cinematography, and dynamic camerawork, the director critiques the cyclical nature of state-perpetrated violence, highlights the alienation and powerlessness experienced by those in the banlieues, and reveals the harrowing consequences of this systemic neglect and hostility.

From the beginning, La Haine immerses the viewer in a cycle of violence that feels both immediate and inevitable. To highlight the inevitability of this violence, the director uses the motif of a ticking clock throughout the film, with ticking being established at the start of the film with a gunshot following it, as the camera zooms into Saïd’s face (05:56-06:11). The constant ticking and the cuts to frames showing the time of the day marks the timespan of the film, highlighting the single-day story and situates the events of the film as routine in the banlieue. The ticking mirrors that of a countdown or a bomb, intensifying the sense of helplessness and the inevitability of the impending violence that lies at the end of it. The final tick occurs right after Vinz’s ‘accidental’ death at the end of the film, with Saïd in the background positioned in a manner that parallels the opening scene, with Hubert and the skinhead pointing guns towards each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1

With a gunshot, the final scene abruptly cuts to black creating a physical loop back to the opening scene, portraying the never-ending cycle of systemic violence and its inevitability. Along with the ticking, the motif of the gun also acts as a powerful narrative device that reinforces the film’s critique of systemic violence. Vinz’s obsession with the gun, as he mimics Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976), showcases how both characters view the weapon as a means of reclaiming control in a world that disregards them. Vinz’s fate, however, proves that in the banlieue power through violence is an illusion. The gun pointed by Hubert in the last scene, that was stolen by Vinz from the riot— a direct consequence of police brutality— becomes a symbol for both retaliation and entrapment, as Vinz believes possessing it grants him agency, yet it only furthers his vulnerability as witnessed through the breakdown of his bravado when he cannot use it on the skinhead in Paris (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The stolen gun serves as an allusion to the violence from which it was taken, compelling viewers to recognise the harsh reality the characters face, as introduced by the black and white archival footage of riots in the opening sequence. The documentary-style footage blurs the line between reality and fiction as the viewers witness clips of protestors facing the police (01:38-05:10), portraying the ongoing reality for the communities and individuals affected by police brutality and allowing the audience to witness the oppression faced by marginalised communities as a continuous cycle. Using these motifs, Kassovitz establishes the context of systemic violence within which the residents of the banlieue exist, trapping them in a cycle of circumstances beyond their control.

Further, Kassovitz also uses physical spaces in La Haine to reflect the entrapment and alienation of marginalised communities by portraying the banlieue as both a physical and symbolic prison, where residents are confined and socially marginalised. The towering apartment blocks are first introduced to the audience in a shot of Saïd hollering at Vinz’s building to call him down (Figure 3). The filmmaker uses the grey, monotonous tones of this space to connote decay and uniformity, mirroring how systemic oppression strips individuals and communities of their autonomy, enabling the state to control their lives, exposing the inevitability of the cyclical nature of entrapment by the system. The director uses a handheld tracking shot of Saïd to allow the audience to witness how the buildings loom over him from his point of view as he interacts with residents (Figure 3). The omnipotence of the buildings is highlighted through the mise-en-scène as they physically loom over him, alluding to how this tool of the state pervades into every interaction of the characters’ lives, encroaching upon every detail of their daily reality.

Figure 3

Kassovitz further highlights the suffocating nature of state control for the viewer, through the scene when the DJ plays a mix of Sound of da Police and Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (41:13-42:19), right after Hubert and his mother watch a news report on the ‘missing’ police gun that was stolen by Vinz (37:33-37:50). The contrasting songs—one critiquing police brutality and the other being a nostalgic number tied to France’s past—create a stark juxtaposition that reflects the dichotomy between resistance against systemic oppression and resignation due to the inevitability of state violence. This scene seamlessly transitions into a bird’s eye view of the banlieue, where the enclosed architecture in the foreground contrasts with the faint silhouette of the Parisian skyline in the background (Figure 4), ingraining the area’s isolation from mainland France in the viewer’s minds.

Figure 4

The gradual zoom-out of the camera intensifies this sense of entrapment, positioning the banlieue as a modern-day panopticon, a uniform, circular structure designed for constant surveillance and control, different from the ‘free’ modern cityscape positioned in the back. By framing the city as just within sight yet unreachable, Kassovitz frames the banlieue as not only a physical prison but also a socioeconomic one, deliberately keeping its residents excluded from the elite Parisian lifestyle. The director further underscores this exclusion by using a shift in the setting as the trio ventures into Paris. When they enter an art gallery in Paris, their presence immediately disrupts the polished atmosphere— gallerygoers stare, the curator glares at them, and a suited man walks past, visually juxtaposing the boys against the elite (Figure 5).

Figure 5

By framing them within a space of wealth and cultural capital, Kassovitz draws attention to their exclusion, showing their marginalisation as not just geographical but something ingrained in the broader institutional systems that perpetuate inequality. The banlieue is therefore not just a place of residence, but a symbolic prison, reinforcing how state-driven alienation operates as a form of systemic violence.

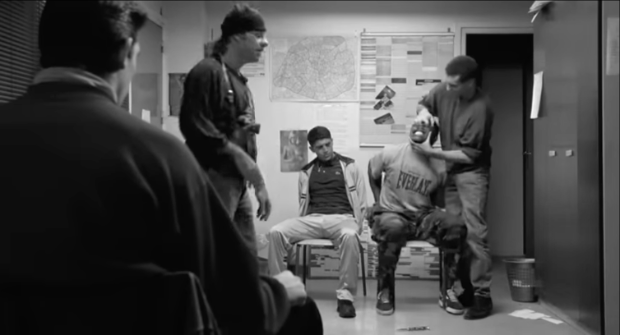

Additionally, by foregrounding the banlieue as a prison, Kassovitz not only portrays the pervasiveness of systemic violence but also exposes its long-term consequences and how they shape the lives of those affected by it. This is most evident in the police station scene, which occurs right after Hubert and Saïd get arrested in Paris (01:03:38-01:05:09), where the boys are tortured by officers with an ignorantly playful demeanour who treat violence as routine. The use of the static position of the camera in this scene positions the audience as passive witnesses, forcing them to spectate the brutalisation of the boys (Figure 6), mirroring the way institutional violence is ignored and normalised.

Figure 6

Further, the director showcases how this bigotry extends beyond the police to the media, and in turn to populations of France, through the scene of the reporter questioning the trio about the riots (21:00-21:03). Kassovitz composes the mise-en-scène in a manner that places the reporter at an elevation and the trio below in the playground, which is enclosed by a metal grill, mirroring a cage (Figure 7).

Figure 7

By placing her above the trio, the reporter is literally and symbolically looking down on them, reinforcing the idea that the people who live in the banlieue exist to be observed not understood. By composing the shot with details that mirror the cage of zoo animals along with Vinz’s dialogue of “this ain’t no zoo” (21:46-21:48), Kassovitz highlights the dehumanisation of marginalised communities in France and how their attempts to reclaim humanity amid state and media-driven prejudice remain futile. In the final scene, Kassovitz portrays the most brutal consequence of institutional violence. Vinz, who once saw the gun as a symbol of power, dies unarmed, his reclamation of power subverted because Hubert, the one who rejected violence, now holds the gun, caught in a moment where a violent end feels inevitable (01:36:04-01:37:01). The film then immediately cuts to black (01:37:03-01:37:14), the abrupt ending emphasising how the characters are forced to remain in the inescapable cycle of violence.

Through its deliberate use of symbolism and cinematography, La Haine exposes systemic state violence as an unrelenting force that shapes and ultimately destroys individuals and communities. Kassovitz employs stark visual contrasts, documentary-style filming, and cyclical imagery to illustrate how institutional brutality is not just a momentary affliction but a sustained mechanism of control. From the ticking clock to the film’s abrupt ending, every cinematic choice reinforces the inescapability of this violence, highlighting not only the ways in which the state enforces oppression but also the continuing consequences it leaves in its wake.

References

La Haine. Directed by Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995.

Onur, Zeynep. “French Banlieues and the Consequences of Spatial Segregation .” Howard University COAS Centers, 2024, coascenters.howard.edu/french-banlieues-and-consequences-spatial-segregation.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “What Is Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon? | Britannica.” Britannica, www.britannica.com/question/What-is-Jeremy-Benthams-panopticon.