LEAFF 2020 celebrates its fifth year with a programme of ten films from celebrated and debut film makers. Championing East Asian cinema, LEAFF aims to bring a wide range of cinema to London and offer the opportunity to experience a new culture of cinema.

Bryn Chiappe assesses the jarring effects of a Hong Kong animation exploring a love triangle amidst the 1967 anti-colonial revolution.

Watching No. 7 Cherry Lane without having any expectations of the film or prior knowledge of the work of Yonfan, I remain unsure whether these things would have improved or detracted from my experience. In trying to capture the pervading feeling one gets while watching the film, the best adjective I’ve been able to come up with is intoxicating. Intoxicating because at times its atmosphere is utterly absorbing – the colour scheme seems to be in competition with the score for their potency and excess – but also intoxicating in the sense that it feels increasingly disorientating and aimless the more of it one sees. The feeling I was left with was not dissimilar to that of leaving a party several hours and drinks later than you should have done – tired, confused, and debating whether the feeling in your stomach is one of emotion or nausea.

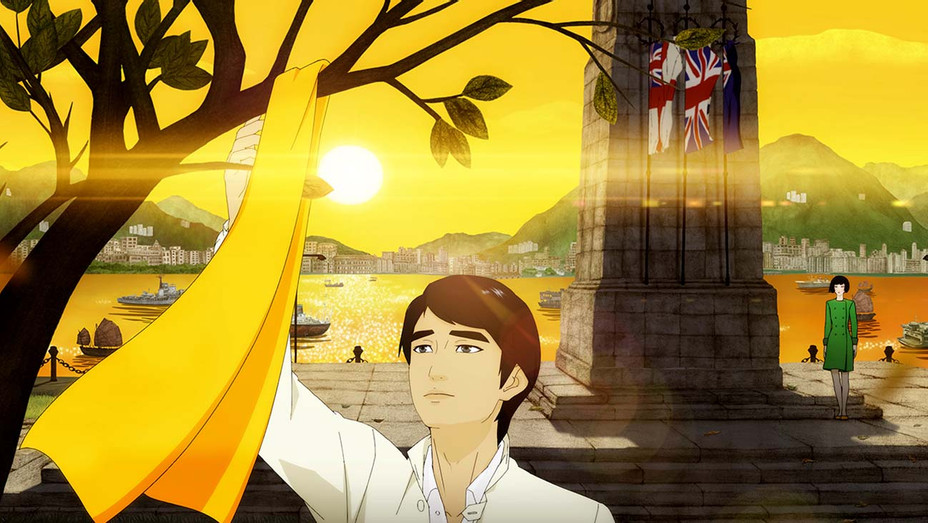

No. 7 Cherry Lane is completely unique from an aesthetic sense. Rendered in 3D before being hand-drawn in 2D, the film has a quality of hyper-stylised beauty that seems to build on the established look of anime in a really original manner. It’s quite a jarring thing to get used to – after the beautiful first shot of a plane casting its shadow over 1967 Hong Kong while a woman sits on her balcony unperturbed, we launch into some very heavily kinetic sequences which are visually striking but also strongly induce motion sickness. Ultimately the aesthetic style is something that the viewer grows accustomed to fairly early on. So, while there are moments when the extravagance of the frame composition feels a little over-the-top, the film’s style is more memorable for being bold and creative than anything else. It helps that No. 7 Cherry Lane grows to use more static, tableau-like framing as it goes on. There’s something about the various 2D layers of the image that feels reminiscent of old video games in quite a sweet, nostalgic way. It’s fitting to have this sense of the past creep into the form that the picture itself takes, given the obsessive extent to which the film takes place in the retrospective mode.

No. 7 Cherry Lane’s gaze being firmly directed at the past is established early on and is a rare continuity in the usually scattered narrative. Ziming, the central character, is a student at the University of Hong Kong studying English Literature. He spends his seemingly endless free time tutoring the eighteen-year-old Meiling in great novels of the past and conversing in-depth with her mother about their favourite literary works. There’s always a decision made to sacrifice subtlety for signposting or homage when a one work of art appears in another, but it has regularly been done with more taste and less superficial romanticism than it is here. The novels discussed create an interesting note in terms of their relevance to the identity crisis of living in a British colony on the other side of the world, but the film feels less interested in this conversation than it does in hammering home the fact that Ziming loves ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ by Marcel Proust. It’s far from nuanced. The regular trips that Ziming takes to the cinema with each of the women create a similar effect. While they function as good plot devices for tracking the development of the relationships, there is an inordinate length of time dedicated to scenes from old films which serve only to create a sense of nostalgia, instead of working on any intertextual basis that moves the story forwards.

The year 1967 saw the Hong Kong riots against British colonial rule, which serve as the backdrop to the story. The perspective of looking backwards leaves a lot of implicit content about the point from which we are looking back, but quite how much the film is in dialogue with the protests seen against the central Chinese government during 2019-20 is hard to gauge. There are no lines that seem particularly loaded with meaning in reference to the present, but the comparison in the viewer’s mind is somewhat inescapable. There’s a happy coincidence for the film in the fact that the riots aren’t the only example of the phenomenon that Bertolt Brecht described as a “critical fracture point” – a transitional period of history marked by violent contrast between the old and new. The cultural transition taking place in Hollywood that saw power diverted away from the studio system and toward auteur directors can be pinpointed at the year 1967, as it very convincingly is in Mark Harris’ book ‘Scenes from a Revolution: The Birth of the New Hollywood’. This isn’t an explicit parallel and feels like something of a wasted opportunity in No. 7 Cherry Lane. We see some old Hollywood epics, Dr Zhivago for instance, and see the new wave in The Graduate, but the contrast between them is left unacknowledged. Instead, we get a relatively simple game of references being performed (an older woman and younger man going to see Mike Nichols’ classic is such a basic use of comparison as to feel disrespectful), without a more substantial weight to the meaning of the films in relation to their time period.

The most interesting things about the film feel unintentional. Hong Kong’s riots are left fairly unexplored despite the rich promise they initially present for a retrospective comment on colonialism. They remain on the fringes of the film’s attention, very much secondary to a love triangle that is quite unsettling in its politics and is formed out of quotes from great love stories in literary history, providing the characters’ romance with very little unique substance. Meiling’s assertion that “tomorrow belongs to me” feels like an afterthought in redirecting the film towards where it should have been heading. The gaze of the story is set so firmly towards the past that the necessary jerk into looking forwards slips out of reach. As a viewer, one is left in a kind of limbo of narrative stasis, wrapped up by constant urging to connect to the film’s nostalgia, yet struggling to gain any purchase on the story itself due to the prioritisation of style over substance.

There are some good elements to No. 7 Cherry Lane, but it generally felt like they were wasted opportunities, lost amidst a sea of half-baked ideas. There’s also a dream sequence where Ziming receives something resembling oral sex from two cats. I thought that this was worth noting, although not worth spending much time mulling over, which also happens to be my thoughts on the film as a whole.